When a fight to ‘free the beaches’ rippled beyond the coast

When a fight to ‘free the beaches’ rippled beyond the coast

The most well-known scenes from the civil rights movement unfolded on buses and in churches, at schools and polling stations, on city streets and the National Mall. A new book by historian Andrew W. Kahrl explores a lesser-known front in the fight for equality: the beach.

In Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline, Kahrl tells the story of grassroots activists in northern cities who challenged segregationist policies and attitudes that kept kids and families of color from enjoying the public beaches along the Connecticut coast.

We sat down with Kahrl to learn more about the history of keeping America’s coastline open to all.

In the ’60s and ‘70s, activists moved to safeguard public access to beaches. Some states, like Texas and Oregon, passed early legislation to ensure everyone could reach the coast. But elsewhere, private landowners tried to draw a line in the sand. Photo credit: Sean Davey

In the ’60s and ‘70s, activists moved to safeguard public access to beaches. Some states, like Texas and Oregon, passed early legislation to ensure everyone could reach the coast. But elsewhere, private landowners tried to draw a line in the sand. Photo credit: Sean Davey

Who was Ned Coll and what did he do?

Coll was an activist who tried to draw attention to inequity in the urban Northeast—far from the center of the civil rights movement in the Jim Crow South. He challenged middle-class, mostly white people—who professed to care about segregation and poverty—to actually spend time in poor communities of color.

Through his work in cities like Bridgeport and Hartford, Connecticut in the 1970s, Coll got to know parents whose kids had no access to safe places to play outside close to home. Through summer camps and day trips, he worked to provide access to the Connecticut shore for low-income, mostly black and Latino youth.

The residents of these shoreline communities, by and large, met the arrival of kids from the city with hostility and went to great lengths to keep them off of beaches that they considered their own.

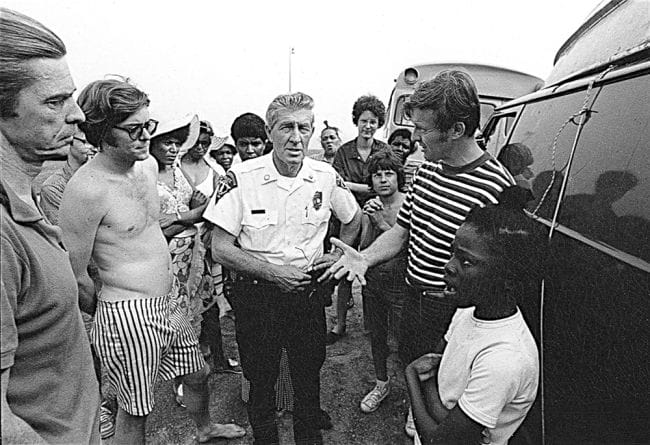

Coll, in the striped shirt, worked closely with families raising kids in cities without safe places to play. Their efforts to integrate the exclusive beaches on the Connecticut coast were often met with hostility.Photo credit: Yale University Press

Coll, in the striped shirt, worked closely with families raising kids in cities without safe places to play. Their efforts to integrate the exclusive beaches on the Connecticut coast were often met with hostility.Photo credit: Yale University Press

What drew you to this story?

I think it shows the various ways segregation is enforced in America. Along the Connecticut shore in the ’60s and ’70s, you didn’t see “Whites Only” signs or explicitly racial policies of exclusion as you would have in the Jim Crow South. But segregation was enacted through a variety of measures—some very subtle, and all ostensibly colorblind—that nevertheless created a separate and unequal society.

What did those measures look like?

Private beach associations proliferated on the Eastern Seaboard in the first half of the 20th century. These were essentially gated communities along the coast that restricted beach access to residents and their guests. In Connecticut alone by midcentury there were more than a hundred, which left fewer and fewer publicly owned beaches.

On top of that, a number of coastal towns owned beaches and restricted access to residents only—even though it was often state and federal money that paid to protect these beaches and restore them after storms. So if you weren’t fortunate enough to own a cottage by the shore or live in one of these wealthy communities—which had near uniformly white populations—the only way you could access the coast was at a small number of very overcrowded and often dirty public beaches.

This was a time when segregation was resulting in poverty, joblessness, and unrest. What made Coll’s group focus on beach access?

Many cities at this time had budget problems, and recreation resources were often first on the chopping block. Even when pools, parks, and playgrounds were built, they were built predominately in white neighborhoods. So for African American kids living on, say, the North End of Hartford, there were very few opportunities to cool off in a safe, supervised place.

As a result, children were hurt, or died. In Hartford, parents in public housing projects staged protests and demanded that officials fence off a part of Park River where eight kids had drowned over course of several years. In Harlem, African American children were hit by cars while playing in street for lack of a better option. Meanwhile, in neighboring affluent towns, white children were playing on clean beaches, watched over by paid lifeguards.

For Coll and the families he worked with, beach access was not some minor issue. It was critically important. And it sure wasn’t the only issue, but it did bring a larger set of problems into focus.

In Connecticut today, The Trust for Public Land is working to improve access to the Bridgeport waterfront and to reinvigorate neighborhood green space—including Johnson Oak Park.Photo credit: Jenna Stamm

In Connecticut today, The Trust for Public Land is working to improve access to the Bridgeport waterfront and to reinvigorate neighborhood green space—including Johnson Oak Park.Photo credit: Jenna Stamm

How did officials respond to those protests?

Some officials reacted to the anger and unrest over these tragic events with piecemeal fixes. The Johnson administration rushed through funding for a slew of shoddy wading pools in poor neighborhoods, for instance, or put sprinklers on fire hydrants. These responses showed how badly officials missed the point of protests around recreation. These were Band-Aids over the gaping wound of segregation.

Why was it important to you to tell Coll’s story?

Ned Coll appreciated that to build a democratic society, we have to protect public space—and ensure that we’re guarding opportunities for meaningful engagement with each other across race and class lines. Coll was very troubled by fact that before his eyes in middle-class Hartford, white Americans were segregating themselves selves in enclaves and having fewer and fewer interactions with people of color.

The Trust for Public Land helped protect Florida’s American Beach, one of the few beaches in the state that was open to African Americans in the first half of the 20th century. Photo credit: Courtesy of Ernestine Smith

The Trust for Public Land helped protect Florida’s American Beach, one of the few beaches in the state that was open to African Americans in the first half of the 20th century. Photo credit: Courtesy of Ernestine Smith

This was especially troubling because in a segregated climate, prejudice can flourish and go unchallenged. Coll saw public space as an essential counterweight to that, a natural way for people of different backgrounds and experiences to come together and figure out how to get along and get to know each other. Without those interactions in public spaces, our democracy and our society would be in a dangerous place.

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge President Biden to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.