In New Mexico, mapping Georgia O’Keeffe’s legacy on the land

In New Mexico, mapping Georgia O’Keeffe’s legacy on the land

Georgia O’Keeffe traveled and painted all over the world, but for much of her life, the high desert of northern New Mexico was her home. Her paintings of the sculpted badlands, adobe structures, and mountains north of Santa Fe solidified her reputation as one of the 20th century’s most influential artists. And tales of her solo explorations through the desert, in search of a place to set her easel, made her a cultural icon: it was a rare thing back then for a woman to wander alone in the sparsely-populated West.

Today, her home at Ghost Ranch near the tiny town of Abiquiú is preserved as part of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, surrounded by the landscapes that she helped make famous. Visitors to the house at Ghost Ranch can look out to the horizon and see the same desert vistas that were the real-life inspiration for some of O’Keeffe’s most iconic paintings.

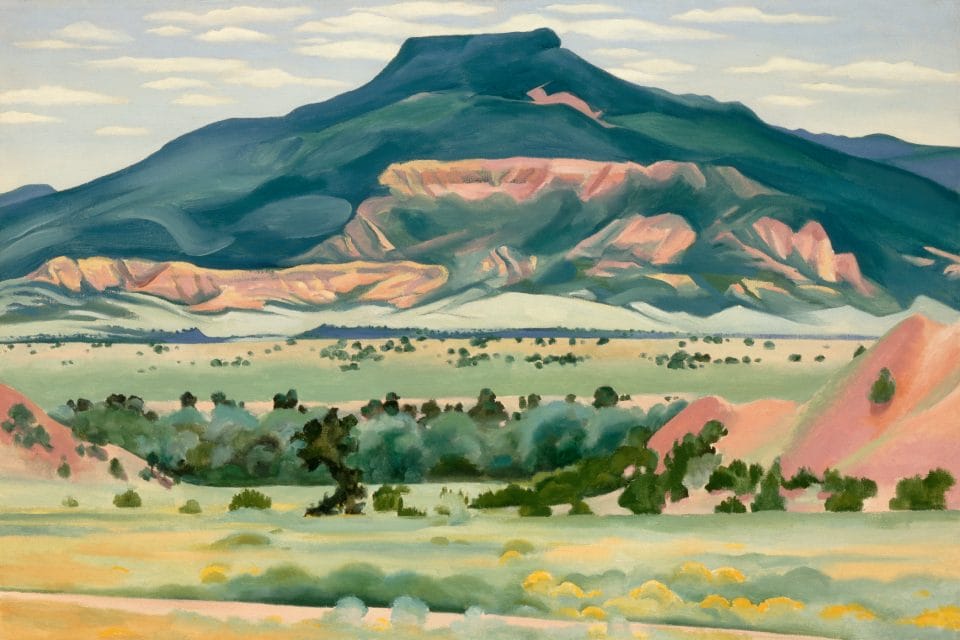

Cerro Pedernal, viewed from Ghost Ranch. This scene was a favorite subject of Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings.Photo credit: Georgia O’Keeffe. My Front Yard, Summer, 1941. Oil on canvas, 20 1/16 x 30 1/8 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. [2006.5.173]

Cerro Pedernal, viewed from Ghost Ranch. This scene was a favorite subject of Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings.Photo credit: Georgia O’Keeffe. My Front Yard, Summer, 1941. Oil on canvas, 20 1/16 x 30 1/8 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. [2006.5.173]

“Out here, you can stand where she stood and see what she saw,” says Ben Finberg, operations director at the O’Keeffe Museum. “For people who’ve been influenced by her art or her story, that’s a pretty special feeling.”

The desert retains its timeless beauty, but after decades of fracking and oil exploration in the region, its lonesomeness is tempered by more roads, tanker trucks, and drill rigs. “Between population growth and oil and gas exploration, these iconic landscapes that are a living part of O’Keeffe’s legacy are under threat,” says Finberg. “In a lot of cases, there is no guarantee that these landscapes are going to be recognizable to the public in the future.”

The museum’s staff is part of a community of O’Keeffe fans who hope to protect now-threatened scenes that the artist painted in northern New Mexico. But first, they needed to find out where they are. So earlier this year, the data experts at The Trust for Public Land teamed up with Finberg’s staff to produce a custom interactive digital experience that maps and catalogs dozens of known locations depicted in O’Keeffe’s works.

The Georgia O’Keeffe 3D Landscape Viewer uses Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology to juxtapose 28 of O’Keeffe’s works across New Mexico with photos of the same scenes taken in the present day. An accompanying “Decision Support Tool,” designed to guide land conservation efforts, documents roads, trails, wildfire risk, land ownership, and other details.

“We figure identifying and mapping these views is the first step toward working with conservation organizations and government agencies to protect them,” says Finberg. He took the photos that appear in the landscape viewer, spending months researching sites, and tracking down friends of Ms. O’Keeffe to pinpoint the spots she painted from.

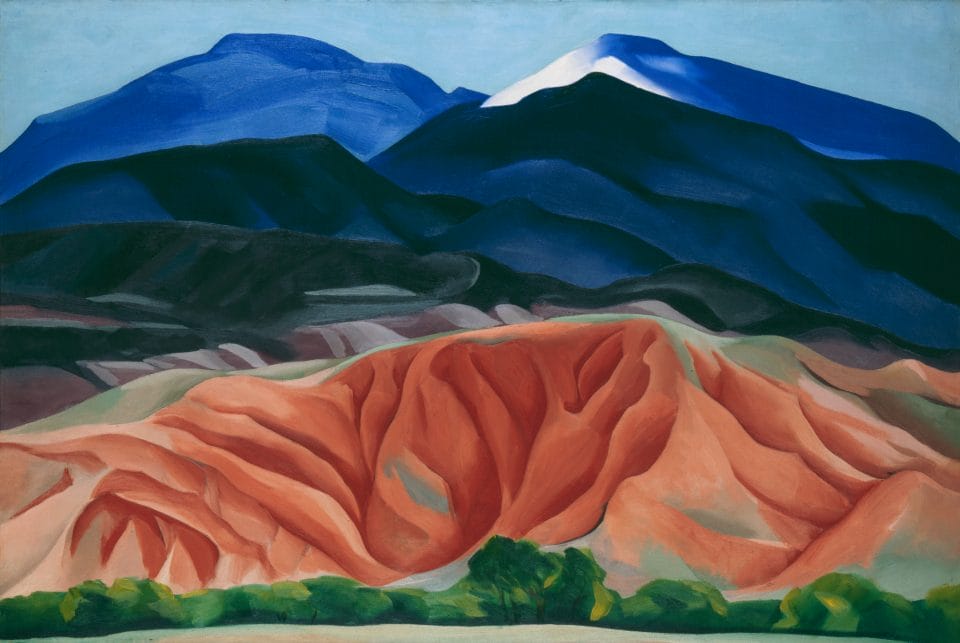

With the Georgia O’Keeffe 3D Landscape Viewer, users can pinpoint spots on a digital map where O’Keeffe created famous works like ” Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II”Photo credit: Georgia O’Keeffe. Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II, 1930. Oil on canvas, 24 1/4 x 36 1/4 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. [1997.6.15]

With the Georgia O’Keeffe 3D Landscape Viewer, users can pinpoint spots on a digital map where O’Keeffe created famous works like ” Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II”Photo credit: Georgia O’Keeffe. Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II, 1930. Oil on canvas, 24 1/4 x 36 1/4 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. [1997.6.15]

“Some sites are more well-documented than others,” says Finberg. “I spent a fair amount of time stumbling around some pretty remote areas, holding up reproductions of her paintings and trying to figure if I’d found the right angle.”

One such outing took him into a patch of eroded canyons and otherworldly badlands almost 150 miles away from her Ghost Ranch home, an area O’Keeffe referred to as “The Black Place.” She returned time and again to the Black Place, on rugged, overnight expeditions, alone or with her close friend Maria Chabot. Between 1936 and 1949 she created more than a dozen major works in this landscape.

The area O’Keeffe called “The Black Place” is in the Bisti Badlands, a wilderness of eroded hills and canyons in northern New Mexico. Photo credit: Flickr user Tony Fernandez

The area O’Keeffe called “The Black Place” is in the Bisti Badlands, a wilderness of eroded hills and canyons in northern New Mexico. Photo credit: Flickr user Tony Fernandez

Michael Namingha remembers first encountering some of O’Keeffe’s Black Place paintings in his art history courses at the Parsons School of Design in New York City. “Growing up in New Mexico, it’s not possible to not know of Georgia O’Keeffe,” says Namingha, an member of a prominent family of artists in the Southwest. But he hadn’t considered her a direct influence until 2017, when the museum invited him to create a series of contemporary works in response to O’Keeffe’s Black Place pieces.

The piece Namingha remembered from art school is called Black Place II. “It’s abstract, but it looked to me like two cloud formations split by a bolt of lightning,” he says. He learned from the O’Keeffe Museum’s curator that it was actually a landscape painting, and it was made at the Black Place—not too far from where Namingha had grown up. “That piqued my interest. I started to dig deeper, trying to find out: where is this place? Is it actually black? How do I get there?”

He began his explorations of O’Keeffe’s historic works using a thoroughly contemporary tool: Google Earth. “I started zooming in and out on my screen, experimenting with this distorted view of the topography you can get. And I started picking up on all these straight lines and little rectangles on the landscape,” he says. He soon realized the lines were roads built by oil companies, and the rectangles were dozens of barrels and tanks.

Next Namingha journeyed to the Black Place in person. Rather than hauling a studio’s worth of easels, canvas, and paint, he came armed with a single tool: a drone that shoots high resolution photography. In the course of four trips, he collected images and videos that became the basis of a series that was eventually displayed alongside O’Keeffe’s work at the museum.

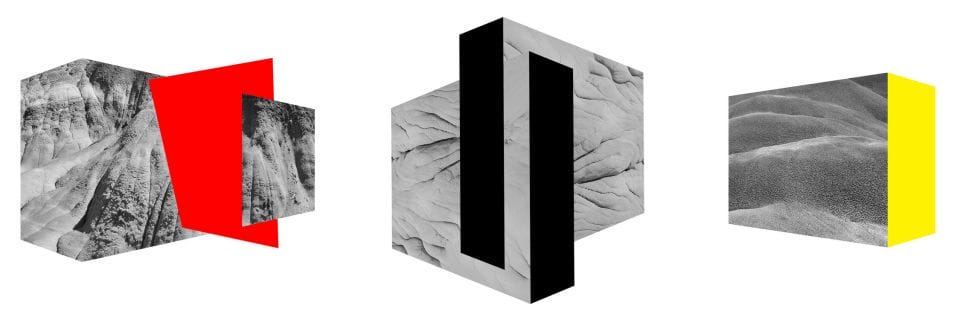

Black Place #1, Copyright 2019 | BP12, Copyright 2018 | BP5, Copyright 2017 | Digital C-Print Face-Mounted to Shaped PlexiglasPhoto credit: Michael Namingha

Black Place #1, Copyright 2019 | BP12, Copyright 2018 | BP5, Copyright 2017 | Digital C-Print Face-Mounted to Shaped PlexiglasPhoto credit: Michael Namingha

Like O’Keeffe’s Black Place paintings, Namingha’s works are abstracted takes on the area’s mesmerizing topography. Angular polygons in bold colors indicate how the Black Place has changed since O’Keeffe’s day: yellow for the surveying flags planted by mineral companies, red to symbolize the cloud of methane gas that NASA has detected hanging over the basin, and black, which “represents the pieces of the landscape that may not be there some day,” he says.

“These are all areas I grew up driving through or experiencing as a kid,” he says. “I went away to New York City for a few years, but when I came back it started to resonate how fragile this place is, and how much of it we’re losing.”

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge President Biden to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.