For Earth Month, a Return to the Roots of the Environmental Movement

For Earth Month, a Return to the Roots of the Environmental Movement

In April 1970, a group of young activists huddled in a makeshift office in Washington, DC, making final preparations for the first-ever Earth Day. Throughout that spring, they’d been working long hours, planting a seed that would grow into a powerful force for global change.

Arturo Sandoval was in his early 20s, already an experienced civil rights activist at the University of New Mexico, when a fellow rabble-rouser recruited him to the inaugural Earth Day organizing team. “We were members of the generation that was coming of age in the 1960s that wanted to do more than what was expected of us,” said Sandoval. In 2020, he took some time to share his recollections of the first Earth Day, and his perspective on where the environmental movement should focus in the decades to come.

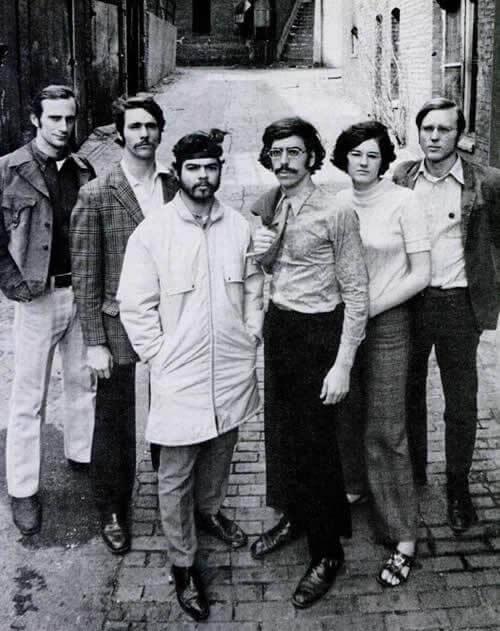

Organizers of the first Earth Day, from left: Denis Hayes, Andrew Garlin, Arturo Sandoval, Stephen Cotton, Barbara Reid, and Bryce Hamilton.Photo credit: Staff of Environmental Teach-In, Inc., 1970, Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society

Organizers of the first Earth Day, from left: Denis Hayes, Andrew Garlin, Arturo Sandoval, Stephen Cotton, Barbara Reid, and Bryce Hamilton.Photo credit: Staff of Environmental Teach-In, Inc., 1970, Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society

Where did Earth Day come from?

It grew out of an idea from Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, who made environmental matters a priority of his public service. Activists had been staging “teach-ins” on college campuses to protest the Vietnam War, and Nelson thought that model of activism might be a good vehicle to get young people engaged in ideas of environmental protection. Of course, the idea caught on, and it pretty quickly grew way beyond our expectations of something that would take place primarily on college campuses.

What was the state of the environment—and the environmental movement—back then?

A number of events and factors came together by the late 1960s. Famously, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire—that made national news, and shocked a lot of people. I remember flying out to Los Angeles for an organizing trip, and the smog was so bad, I couldn’t breathe.

The Cuyahoga River caught fire—for the last time—in 1969. This iconic image was actually taken in the early 1950s, documenting the shocking frequency with which the river caught fire throughout Cleveland’s industrial history.Photo credit: Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections

The Cuyahoga River caught fire—for the last time—in 1969. This iconic image was actually taken in the early 1950s, documenting the shocking frequency with which the river caught fire throughout Cleveland’s industrial history.Photo credit: Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections

Meanwhile there were no meaningful regulations controlling particulate matter in the air, or pollutants in water. And there was no organized way in which we could express our unease, this sense that we were doing ourselves in.

There was an environmental movement in the US, but it was small and dispersed. It needed a spark. So Earth Day was the spark. It made the whole damn system go up in flames—in a good way, in the best way—by giving people a voice and a way to get really engaged and make caring for our environment a national issue.

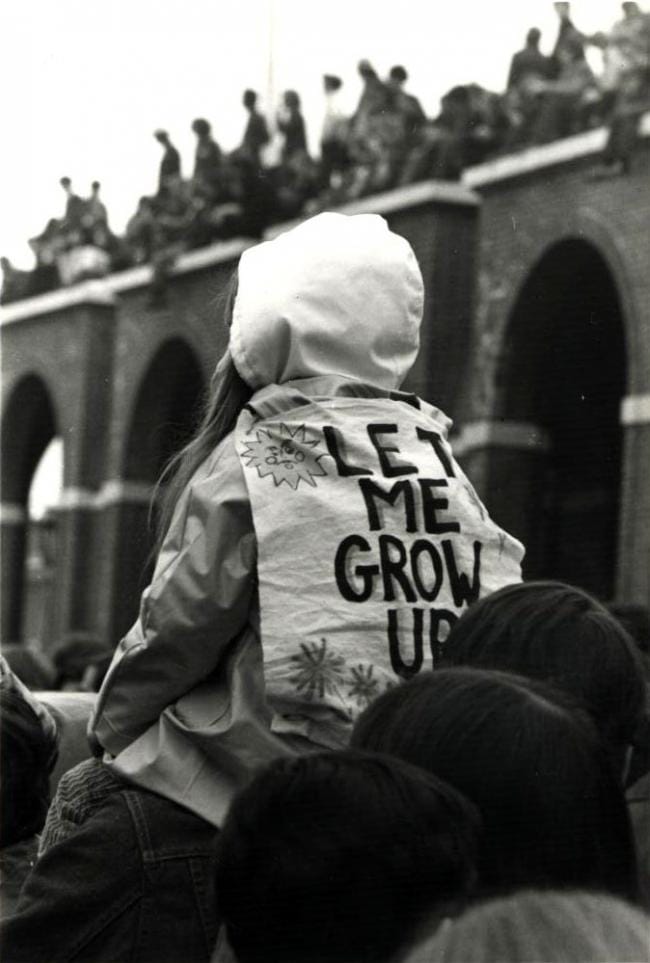

Earth Day gave “people a voice and a way to get really engaged and make caring for our environment a national issue,” Sandoval says.Photo credit: Library of Congress

Earth Day gave “people a voice and a way to get really engaged and make caring for our environment a national issue,” Sandoval says.Photo credit: Library of Congress

How did the social context of the time shape the first Earth Day?

This came right on the heels of the civil rights movements of the 1950s and 60s, which took root in the African American community, which informed the nascent movement for women’s liberation, the anti-war movement, and the rise of Chicano activism, and soon Native Americans joined the struggle.

The methods of mass organizing for social change that had been forged by the leaders of these movements provided an effective model for the environmental movement to follow.

Tell us about some of those methods.

This was before the internet and cellphones, remember. So we mainly did it by mailing out a lot of information, tens of thousands of pieces of mail. We also served as connectors for lots of disparate groups. I was in charge of organizing the Western US. Say I’d get a call from a Boy Scout leader in Portland; I’d go to our files and look up Oregon and tell them, “Hey, there are five other groups who’ve called us wanting to get involved—do you have a pencil? Let me give you their names and numbers.”

But really the main thing that Senator Nelson urged was to keep it decentralized and turn it back to the people. Tell them, “Don’t look to the national organizations to tell you how to do it—just go do it. You know the local issues, go get yourselves organized.” And by gosh, they did it.

What do you remember from the first Earth Day?

We didn’t start off expecting the reaction that we got, but as we were getting closer to the date, it was clear: this was going to be humongous. There were demonstrations in almost every part of the country. All the big news networks covered it. I remember the enormous creativity of demonstrators: people buried cars out in California to show their displeasure with the automobile industry. We had 20 million people in the streets. It was pretty astounding, let me tell you. It was a lot of fun.

A young Earth Day demonstrator in Philadelphia sends a clear message.Photo credit: © 1970 Earth Week Committee of Philadelphia

A young Earth Day demonstrator in Philadelphia sends a clear message.Photo credit: © 1970 Earth Week Committee of Philadelphia

Before you got involved as an Earth Day organizer, how connected were you to the environmental movement?

I was not that familiar with the environmental movement, per se, but I grew up with a sense of place. I was raised poor in a rural community in northern New Mexico, one of 11 kids in a family that had been in that place for about 400 years on our European side, and for at least 7,000 years on our Indigenous side. For me, place is imbued with deep spirituality. It’s a part of who I am. Place is a living, breathing entity that was instrumental in raising me, helping me form the values I hold today.

So no, I wasn’t particularly aware of the environmental movement, but I was aware of those values. Then I became a social justice activist in a very big way starting my first year of college in 1965. I helped start the Chicano student group at the University of New Mexico, organized Mexicano unions, organized food co-ops in rural towns. It was while I was active in all that that I was referred to the Earth Day team.

I was interested in helping organize Earth Day because I believed that the people who were causing inequality in our society were the same people who had no respect for place. The people who would discriminate against African Americans by renting them slum dwellings in New York or refusing them service in restaurants were the same people who would dump mercury in a river. It wasn’t much of a jump at all, really: joining the environmental movement was a logical and holistic extension of work I was already doing as an organizer in the Chicano movement.

“Don’t look to the national organizations to tell you how to do it—just go do it,” Sandoval recalls telling Earth Day demonstrators. “You know the local issues, go get yourselves organized!” Photo credit: © 1970 Earth Week Committee of Philadelphia

“Don’t look to the national organizations to tell you how to do it—just go do it,” Sandoval recalls telling Earth Day demonstrators. “You know the local issues, go get yourselves organized!” Photo credit: © 1970 Earth Week Committee of Philadelphia

What came after Earth Day for you?

I got drafted in July and refused induction. I ended up going to trial: I was one of 4,500 resistors during the whole Vietnam era who were indicted, tried, and convicted. I was sentenced to 3 years in prison and got a deferred sentence, which I served through probation and alternate service.

I’ve gone on from there, dedicated my life to civil rights and other issues. I did find time to get married and have children, and I had a 15-year career in journalism and PR. I’ve participated in campaigns for new wilderness areas in New Mexico—the Sabinoso and the Ojito, and I’ve served as a bridge at times between traditional land-based communities and environmental organizations. In 1991 I started the Center of Southwest Culture, and that’s where I’ve been for the past 28 years. Our mission is to help create healthy Indigenous and Mexicano communities through economic development, education, and cultural programs.

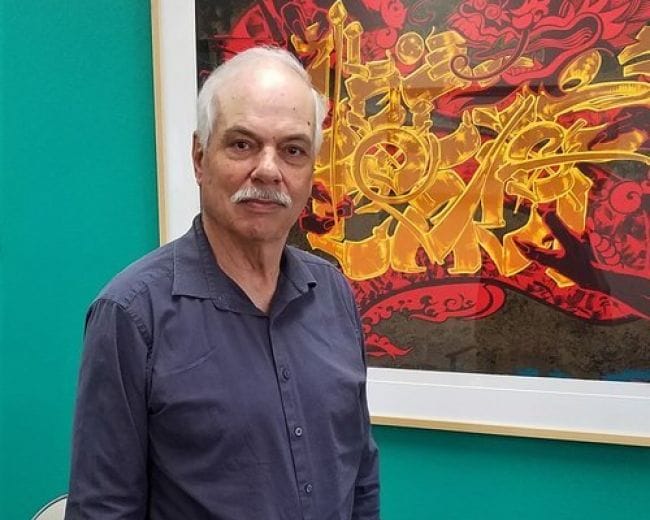

“Retirement is for people who have a golf game, in my opinion,” Sandoval says. “I feel like I’m just getting good at what I do, and still have the rest of life to try to make the world a better place.”Photo credit: Center of Southwest Culture

“Retirement is for people who have a golf game, in my opinion,” Sandoval says. “I feel like I’m just getting good at what I do, and still have the rest of life to try to make the world a better place.”Photo credit: Center of Southwest Culture

What do you think Earth Day has accomplished?

It engaged people across the board. You wouldn’t believe the number of people who were calling about it, and how diverse the calls, and how diverse the communities. And some tremendous legislative successes followed: The Clean Air Act in 1970, the Clean Water Act in 1972—these big national victories created a sense of real achievement as the national environmental organizations evolved and became more sophisticated.

Where do you think the environmental movement needs to focus in its next 50 years?

Unfortunately as the national organizations evolved, they became more insular, and that persists to this day. There are exceptions, but the environmental movement as a whole is very white and classist. Because they had so much success, they didn’t feel the need to broaden their membership and message to working class people and communities of color, especially African Americans and Latinos. After Earth Day I never felt to any great degree that there was a place for me in that environmental movement, though I’ve wanted to be part of it. I think that’s really hurting us now: we no longer have the ear of most Americans.

Youth climate marchers in Washington, DC.Photo credit: Flicker user Justice and Witness Ministries

Youth climate marchers in Washington, DC.Photo credit: Flicker user Justice and Witness Ministries

How do you think today’s young people are living up to the examples you and your peers set in the 1960s and ’70s?

I’ve followed youth climate marches, and I think it’s fantastic. We’re in deep trouble right now in terms of trying to save the planet. But there is absolutely no future in cynicism: you can’t give up, and you shouldn’t. We need to elect good people, need to resist, need to always raise our voices. Action is a great way to create hope, and people need to have hope to survive.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.