“What would Jim do?”

“What would Jim do?”

If you’ve taken a hike anywhere within an hour’s drive of Seattle, chances are, you have Jim Ellis to thank for it. A legendary civic leader who passed away in 2019 at age 98, Ellis was the force behind an extraordinary range of public projects throughout the Puget Sound region. As a young lawyer in the 1950s and 60s, Ellis led the drive to clean up Lake Washington, which was so polluted from decades of untreated sewage that locals compared it to split pea soup. In the 1970s and 80s, Ellis rallied support for ballot initiatives that would fund city parks, pools, farmland preservation, and transit for the already rapidly growing region.

And in the early 1990s, he headed up the creation of the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust, the nonprofit that stewards a 100-mile corridor of public lands and trails stretching from Seattle to the city of Ellensburg in the eastern Cascade foothills.

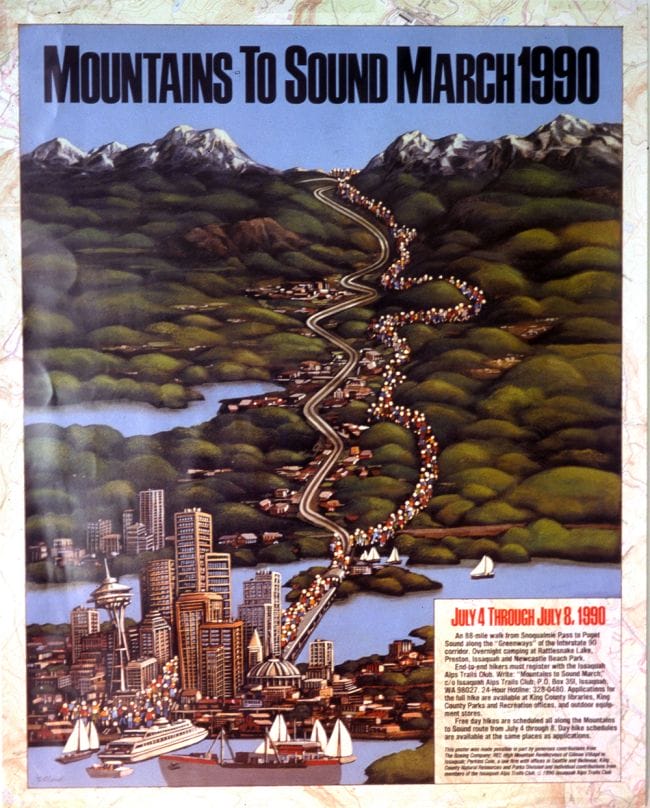

In 1990, Doug McClelland joined a five-day march from Snoqualmie Pass to Seattle, passing through and calling attention to many of the special places that would ultimately be included in the Mountains to Sound Greenway. Photo credit: Courtesy Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

In 1990, Doug McClelland joined a five-day march from Snoqualmie Pass to Seattle, passing through and calling attention to many of the special places that would ultimately be included in the Mountains to Sound Greenway. Photo credit: Courtesy Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

Whatever the task, “Jim worked incredibly hard behind the scenes,” says Doug McClelland, president of the Greenway Trust. “He always deflected credit, and he always told the best stories.” McClelland, Ellis, and many others worked together for decades to call attention to the region’s wildlands—and to their shared vision for a greenway that would ensure public access as the region’s population grew. The Trust for Public Land helped launch the Greenway Trust 30 years ago, and we’ve since worked to create public access to over 10,000 acres within the greenway, from rugged mountainsides to peaceful hiking trails to the Olympic Sculpture Park in downtown Seattle.

Trust for Public Land Project Manager Sam Plotkin only had the chance to meet Ellis only once, but says Ellis’s legacy still shapes his work—and his life in Seattle—on a daily basis. “It was because of Jim’s example that I could move to Seattle from a whole different part of the world and get plugged right into this energized conservation community,” Plotkin says. “I mean, not to sound too woo-woo about it, but Jim’s spirit of togetherness and action and finding common cause is so central to what has made the Puget Sound region a lively, engaging place to live.”

The Trust for Public Land has worked alongside partners like the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust to ensure public access to over 10,000 acres within the greenway, from Rattlesnake Ridge (above) to the Olympic Sculpture Park in downtown Seattle.Photo credit: Tegra Stone Nuess

The Trust for Public Land has worked alongside partners like the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust to ensure public access to over 10,000 acres within the greenway, from Rattlesnake Ridge (above) to the Olympic Sculpture Park in downtown Seattle.Photo credit: Tegra Stone Nuess

Ellis was born in in 1921, the eldest of three brothers, and spent most of his childhood in Seattle. After a stint at Yale, as a member of the Army Air Corps during World War II, and a law degree from University of Washington, Ellis launched his career in corporate law—not typically a path that allowed for what you’d call work-life balance.

“But Jim had this philosophy of what constituted a successful life. It was a rule of thirds, sort of: you dedicate one third of your life to your job, another third to your family, and a third to your community,” says Trust for Public Land Seattle Legal Director Tom Tyner, who’s been with the organization since 1993 and worked closely with Ellis on several projects in the Mountains to Sound Greenway.

[Read more: In fast-growing Seattle metro, the need for parks is evergreen]

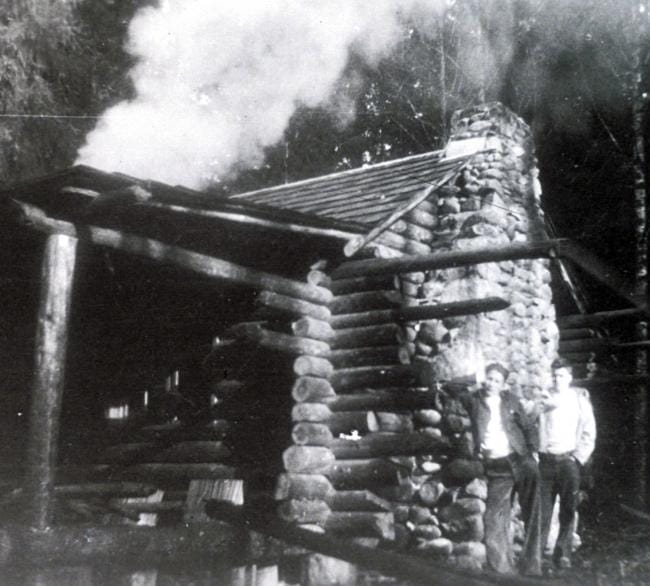

Back in the 1930s, when Seattle was a smoky timber town and Jim and his brother Robert were teenagers, their dad drove the two boys east out of the city to a heavily wooded property on the banks of the Raging River, handed over a few tools, and told them to build themselves a shelter. Then he drove off. “I think the idea was to teach self-reliance, or maybe just keep them occupied,” Tyner says. Whatever the intention, the brothers figured out how to build a small cabin, so sturdy that it still stands today.

Robert enlisted during World War II, and died in combat in 1945—a devastating blow to Jim, and an inflection point in his life that friends and family say motivated him to honor his brother by working hard for his community.

Jim and his brother Bob at the cabin the two boys built near the Raging River in the 1930s.Photo credit: Courtesy Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

Jim and his brother Bob at the cabin the two boys built near the Raging River in the 1930s.Photo credit: Courtesy Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

In the 1980s, after he semi-retired from his law practice, Ellis turned his prodigious attentions to the millions of acres of deep forests, clear rivers, and rugged mountains where he and his brother had spent so much time together as kids. The region was in the early stages of a boom that today is making it one of the fastest-growing metro areas in the country, powered in part by the city’s proximity to the extraordinary opportunities for hiking, biking, skiing, and climbing. But with a dizzying mix of landowners and often-competing incentives, Ellis and his allies realized that preserving these lands and ensuring public access forever would be a complex, long-term task.

The Trust for Public Land, Ellis, and the other founders of the Greenway Trust “recognized the need for a group that would bring all these parties together around a shared goal of a livable community for everyone: conservationists and developers, labor groups and the business community, farmers and fish people,” says Plotkin.

“Another of Jim’s principles was the importance of breaking bread with people,” says McClelland, the current president of the Greenway Trust. Then as now, the Greenway Trust’s massive 60-person board meets regularly over dinners at a community center. “You’ve got timber company reps passing the salt to Sierra Club members, and activists chatting with government officials. It’s a continuation of Jim’s model of bringing people together, dropping labels, and working on a common theme.”

Ellis, right, was an energetic civic organizer and connector, but friends and family say he also worked hard behind the scenes and learned everything he could about the projects he helped move forward.Photo credit: Courtesy Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

Ellis, right, was an energetic civic organizer and connector, but friends and family say he also worked hard behind the scenes and learned everything he could about the projects he helped move forward.Photo credit: Courtesy Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

Over the next 30 years, Ellis and the Greenway Trust worked with partners like The Trust for Public Land to preserve most of the large open lands within the greenway—places like the Raging River State Forest (not far from the cabin Ellis built as a 15-year-old in the 1930s) and the Middle Fork Snoqualmie River Valley. Today the Mountains to Sound Greenway National Heritage Area spans nearly 1.5 million acres crossed by 1,600 miles of trails, a wonderland for outdoor recreation within a short drive of the Puget Sound region’s 4 million people.

[Read more: Solving the puzzle of sustainable growth in the real Twin Peaks]

The next generation’s task? Conserving the smaller properties that could make a big difference for public access, like Hill at High Point, a five-acre parcel on Tiger Mountain that The Trust for Public Land preserved last year, making space for a new trailhead leading to 95 miles of existing trails. In the City of Issaquah, we recently helped the community preserve 46 acres on the slopes of the popular Cougar Mountain Regional Wildland Park, making space for a transit-accessible trailhead connecting downtown Issaquah to over 35 miles of trails.

We recently helped residents of Issaquah improve public access to Cougar Mountain Regional Wildland Park, creating a future trail connection from the park to a transit hub in the heart of town.Photo credit: King County Parks

We recently helped residents of Issaquah improve public access to Cougar Mountain Regional Wildland Park, creating a future trail connection from the park to a transit hub in the heart of town.Photo credit: King County Parks

Whatever the project at hand, Plotkin says, Ellis’s problem-solving spirit continues to guide the conversation today. “If you’re working on a difficult project, or navigating some conflict with a landowner, or trying to engage a city council to prioritize funding for conservation, it’s not uncommon to hear someone say, ‘What would Jim do?’” Plotkin says.

To make more of these projects possible, The Trust for Public Land and the Greenway Trust launched the Jim Ellis Fund for Land Conservation, a dedicated fund to invest in complicated, expensive, but high-impact conservation projects. “There are lots of these little inholdings left in the greenway that will make the difference for access and connectivity in the long run,” says Plotkin with The Trust for Public Land, who pitched in on the efforts to conserve Hill at High Point and the Cougar Mountain property in Issaquah. “We have a responsibility today to finish putting this puzzle together. I think if Jim were alive today he’d be the guy saying, ‘Okay, it’s time, let’s get the ball rolling.’”

[Read more: Working for an evergreen future in the Northwest]

These days, Plotkin and his colleagues are working to expand Olallie State Park near the town of North Bend, including some of the region’s most accessible rock climbing areas and an important stretch of a popular hiking trail. And they’re helping King County protect 26 acres along the Raging River, key for fish and wildlife habitat.

McClelland says his own work with the Greenway Trust—and donations to important projects—are motivated in part to see Jim’s greenway vision through, and also to honor his old friend’s model for making change. “In today’s world when we all find so many reasons to divide ourselves, it’s just as important to perpetuate the spirit of collaboration and hard work that he brought to every project,” he says.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.