A ride to remember: Cherokee cyclists trace the Trail of Tears

A ride to remember: Cherokee cyclists trace the Trail of Tears

When Will Chavez was in school in Oklahoma in the 1970s and 80s, his history textbooks barely mentioned the Trail of Tears. He learned that the Cherokee were driven from their homes in the Southeast by the U.S. government, and that the forced marches resulted in thousands of deaths—but that was about all. “They maybe had a paragraph or two about it, but it was not very detailed,” Chavez remembers.

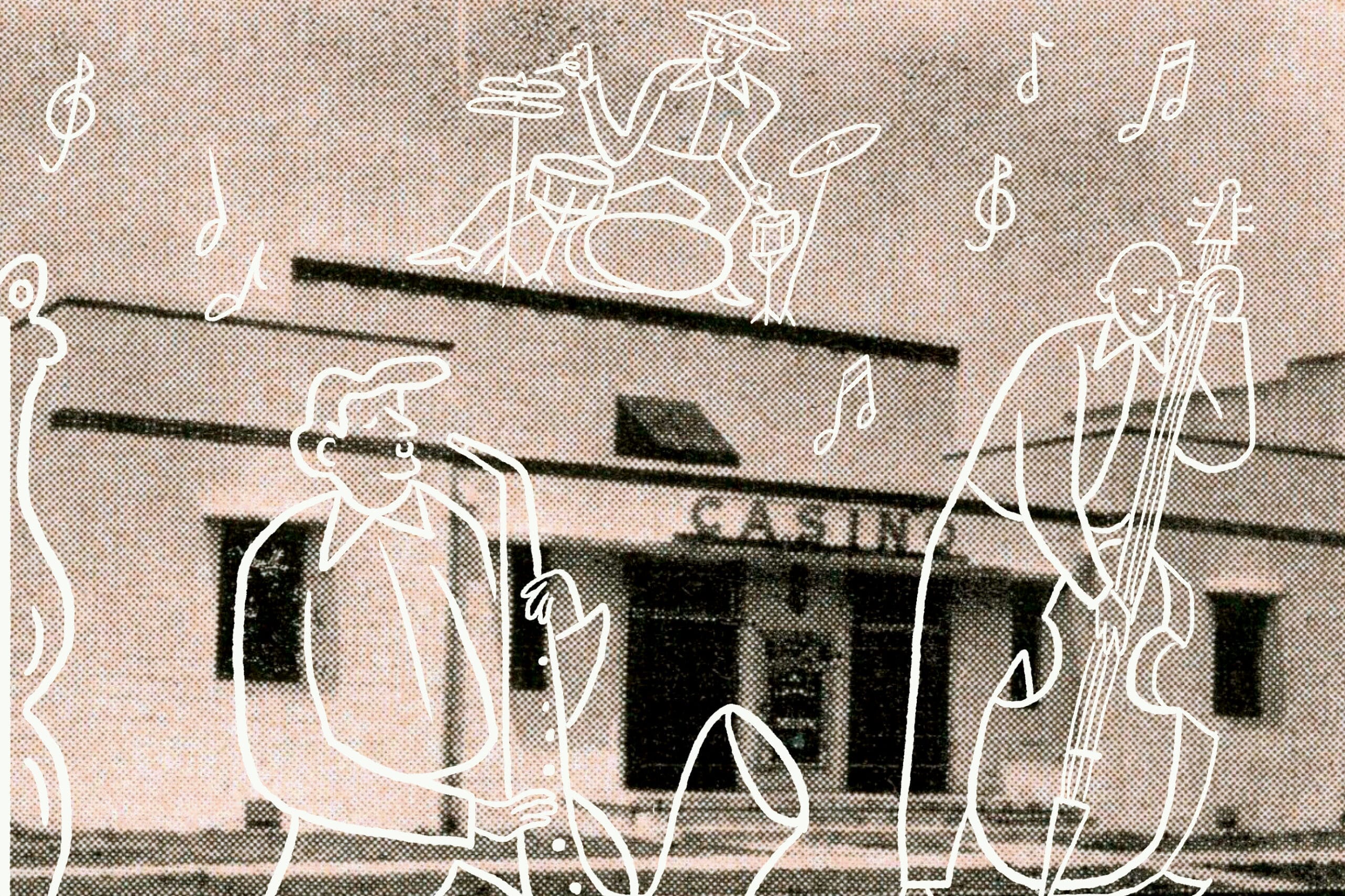

But Chavez would come to know the Trail of Tears firsthand when in 1984 he joined a group of Cherokee youth retracing the historic route by bike. In the 150 years since the removals, the tangible traces of their ancestors’ journey had faded. Within the Cherokee Nation and among historians, there was a growing interest in preserving the route and some of the historic buildings along it. “We wanted to bring attention to the trail in hopes that the federal government would release the funds to mark it,” Chavez says.

In 1984, members of the Cherokee Nation retraced the Trail of Tears by bike. Today, parts of their route are memorialized as the Trail of Tears National Historical Trail.Photo credit: Tom Fields

In 1984, members of the Cherokee Nation retraced the Trail of Tears by bike. Today, parts of their route are memorialized as the Trail of Tears National Historical Trail.Photo credit: Tom Fields

“The other reason we rode was to honor our ancestors and commemorate the removals. On a bike, you get a feel for the terrain and just how steep some of these hills are.” Chavez remembers the slow, laborious grind up the Cumberland Gap in Tennessee, and how he imagined what it would have been like to make the climb pulling a wagon or carrying young children. “It’s tough to ride, and that’s on a road. Back then they were just cutting their own way through.”

From Tennessee, Chavez and his fellow cyclists rode west for three weeks to Tahlequah, Oklahoma, in the heart of the modern Cherokee Nation. Before setting out each morning, the riders circled up to pray—then pedaled along back roads, staying as close as possible to the trails that the Cherokee followed in the 1820s and 30s and stopping at historical sites along the way.

For Chavez, the experience was an intense mix of solemn reflection and daily triumphs. “The ride boosted my self-esteem and made me more adventurous. It was a bonding experience like no other.”

After his return to Oklahoma, Chavez went on to college, and then into the Army. Now 52, he’s assistant editor of the Cherokee Nation’s newspaper—and the ride he and his friends first did in the 80s is an annual event called “Remember the Removal.” A team of 18 young riders is selected through a rigorous application process. Those chosen take training rides around Tahlequah and meet weekly for Cherokee language and history classes. A genealogist prepares a detailed report on each rider’s heritage, so they can pinpoint where their families lived before the removal.

“When they visit these sites back east during the ride, they can know exactly where they came from,” says Chavez. “It’s pretty moving when the riders are able to place their feet where their ancestors stood.”

At Mantle Rock in Kentucky, riders pause to visit the spot where thousands of Cherokee camped during winter of 1938-39, waiting for the Ohio River to thaw so they could continue their passage west. Photo credit: Remember the Removal Bike Ride

At Mantle Rock in Kentucky, riders pause to visit the spot where thousands of Cherokee camped during winter of 1938-39, waiting for the Ohio River to thaw so they could continue their passage west. Photo credit: Remember the Removal Bike Ride

The young riders also have the benefit of an official route: thanks to the work of advocates like Chavez, in 1987 Congress established the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. Today, the National Park Service oversees a coalition of Cherokee Nation members, public agencies, nonprofits, and private landowners that own and maintain hundreds of historic sites along the trail—which spans nine states and more than 5,000 miles of roadways. Anyone traveling the route will encounter road signs and waysides that describe the experience of the Cherokee during the removals. “It helps people—all people—know that those events occurred,” says Chavez. “We just don’t want anyone to ever forget that something like that occurred in this country.”

Chavez’s son participated in the Remember the Removal ride in 2014, and his daughter completed the ride this past summer. Chavez himself mentors and rides with participants, watching them gain strength, confidence, and an understanding of what it means to be a member of the modern Cherokee Nation.

The Trust for Public Land has helped protect sites along the Trail of Tears and keep them open for all. Today, anyone passing through these areas will encounter road signs and waysides that describe the experience of the Cherokee during the removals.Photo credit: Remember the Removal Bike Ride

The Trust for Public Land has helped protect sites along the Trail of Tears and keep them open for all. Today, anyone passing through these areas will encounter road signs and waysides that describe the experience of the Cherokee during the removals.Photo credit: Remember the Removal Bike Ride

During the interview process, applicants are asked what they know about the Trail of Tears. “Some kids can barely give any details,” says Chavez. “As brutal as it is to find out what really happened, it’s good for them to know.” For Chavez, honoring the memory of those who experienced the removals is also a reminder to each rider of how far their people have come. “The Trail of Tears doesn’t define us,” he says. “We’re more than that, we’ve come a long way since that time, and we’re continuing to make strides and recover. This ride is a symbol of that.”

The Active Transportation Infrastructure Investment Program (ATTIIP) is a vital initiative that helps expand trails connecting people to nature and their broader neighborhoods. Despite this importance, Congress allocated $0 for ATTIIP in this year’s appropriations process. We cannot delay investments in safe, active transportation systems. Urge Congress to fully fund the ATTIIP!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.