“Musicians are like weeds,” says Jeff Rupert. “You can’t stop them. They just keep growing through the cracks of the sidewalk, you know?” This is how Rupert, a saxophonist and director of Jazz Studies at the University of Central Florida, explains the tenacity of Black musicians who toured the South during the Jim Crow era of legalized segregation. In Orlando, one of the only places these artists could safely perform and lodge was at the South Street Casino and Wells’Built Hotel, respectively.

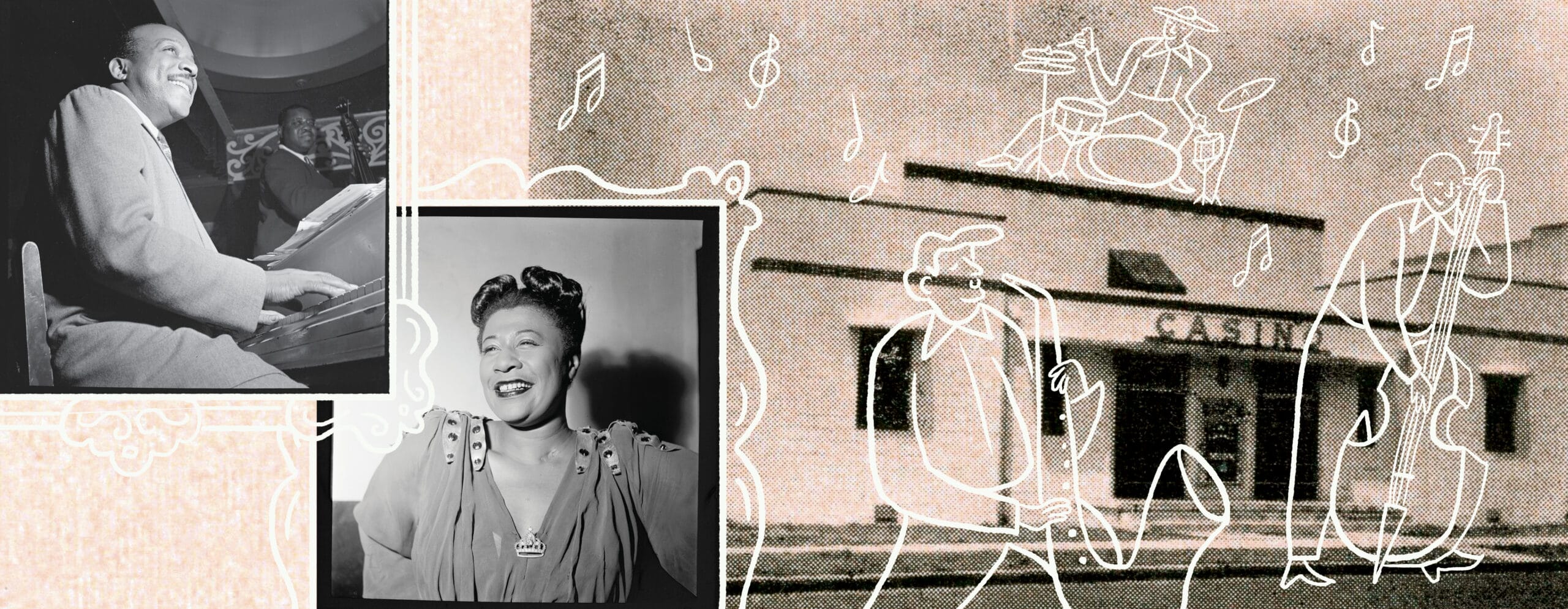

The latter is now a museum of African American history and culture, and the building is still standing today thanks in part to Trust for Public Land. Opened by its namesake, Dr. William Monroe Wells, in 1929, the Wells’Built hosted an almost absurdly impressive list of talents, including Ray Charles, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Lionel Hampton, Dinah Washington, Duke Ellington, B.B. King, Illinois Jacquet, Cab Calloway, Memphis Slim, Billie Holiday, and Louis Armstrong. (And its list of famous lodgers goes beyond musicians; Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and baseball star Jackie Robinson also stayed there.)

These influential musicians played what was known as the Chitlin’ Circuit, a tour route through the South that author Preston Lauterbach described on NPR’s Code Switch as “African Americans making something beautiful out of something ugly, whether it’s making cuisine out of hog intestines or making world-class entertainment despite being excluded from all of the world-class venues.”

CeCe Teneal, an Orlando-based soul singer who travels worldwide with her Aretha Franklin tribute act, says visiting the museum and seeing evidence of those who paved the way for musicians of color gives her own role as a performer new meaning: “They jeopardized their lives to play music, to do the thing they loved,” she says. “Because of the things that these people did for me, I am required to give it my all.”

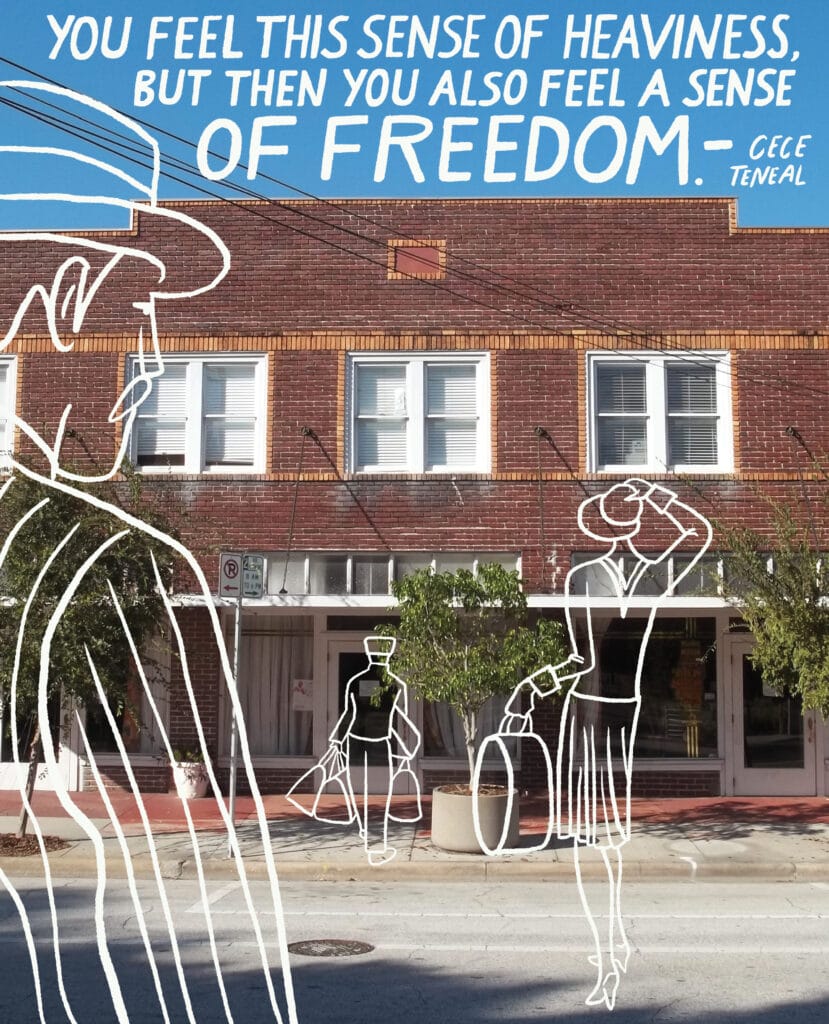

From 1936 to 1966, Black travelers relied on The Negro Motorist Green Book, a publication that listed restaurants, gas stations, hotels, and other establishments that served African Americans. The Wells’Built Hotel, a two-story brick building opened by one of Orlando’s first African American physicians, was the only lodging listed in Orlando. “I’m sure there’s no way to outline the amount of obstacles he encountered,” Teneal says of Dr. Wells, noting his persistence and courage must have been incredible.

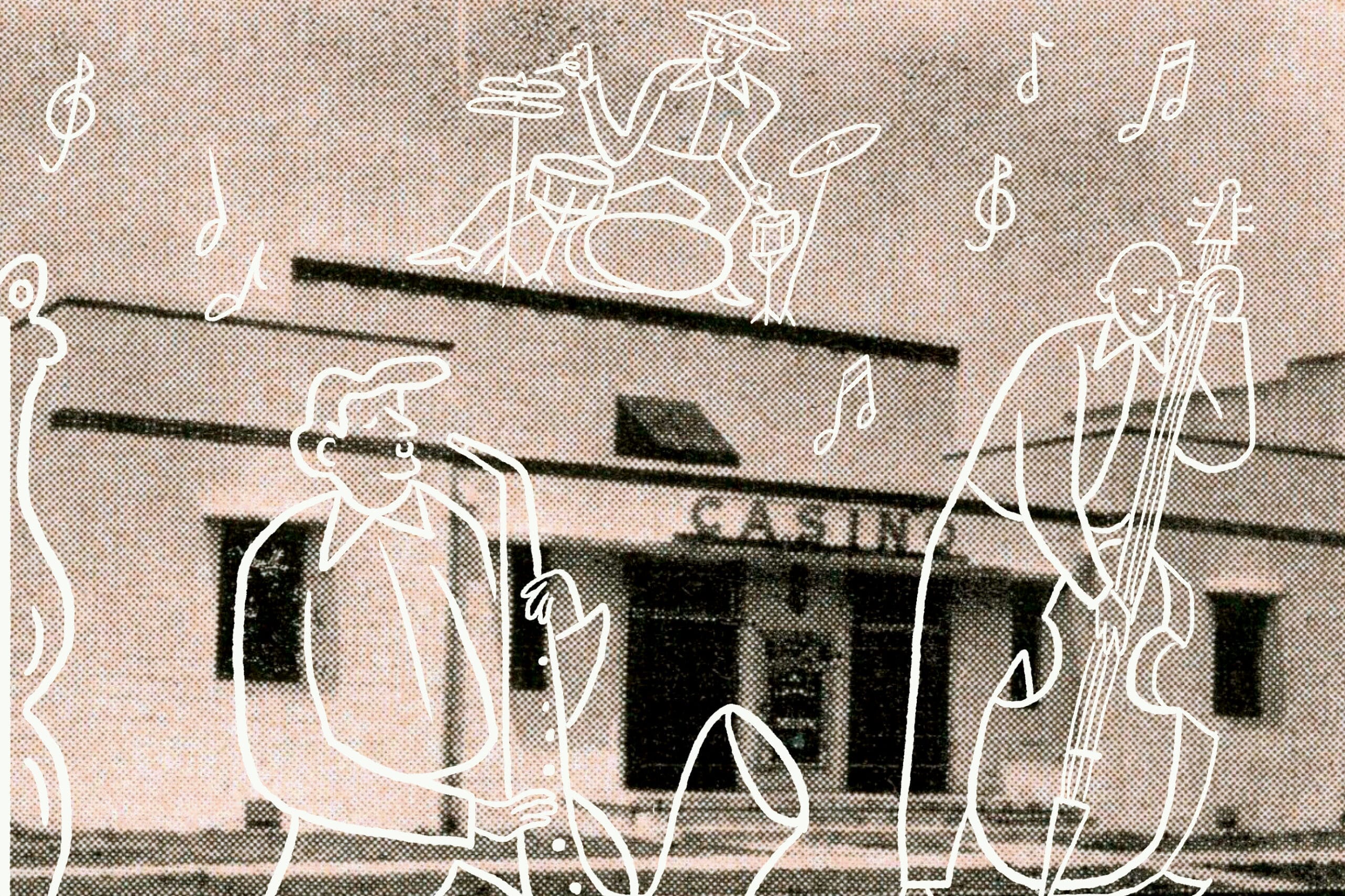

The South Street Casino—which, despite the name, was an entertainment venue and community event center rather than a gambling establishment—was damaged by a fire and demolished in 1987. But the hotel remains. Located in the Holden-Parramore Historic District, what some term Orlando’s Harlem, and situated directly across the street from the Amway Center (where the Orlando Magic play), it almost wasn’t saved at all.

Learn more about our work to preserve sites that tell the story of the Black experience in America.

“It was a bit of a stretch,” says Will Abberger, an Orlando native and director of TPL’s conservation finance program. “The building was in horrible shape, dilapidated; the roof was falling in. I think we ended up hauling 13 dumpster loads of garbage out of it. There were homeless people living there. It’s a wonder it didn’t burn down.”

But former Florida Representative Alzo J. Reddick and current Florida State Senator Geraldine Thompson had a vision for the hotel—and they knew TPL could help see it through. “We were known in the historic preservation world here in Florida,” says Abberger, who was a TPL project manager in Florida at the time. Reddick connected Abberger with Thompson, who is also founder of the Association to Preserve African American Society, History and Tradition (PAST), the nonprofit that runs the Wells’Built Museum.

In a previous, administrative position at Orlando’s Valencia College, Thompson started collecting artifacts and memorabilia related to Black history. She says it got to the point where her collection was taking over the shipping and receiving department, so she started thinking about a museum.

“Then I learned about Dr. Wells and how important both of those structures were in terms of the history of Central Florida,” she says. So she wrote a grant proposal to acquire the hotel, but there wasn’t much time: it was slated for demolition. In 1994, Trust for Public Land purchased the building. Meanwhile, PAST raised funds to cover the cost plus repairs. (TPL and PAST later received various grants to fund renovations and acquire exhibits.)

The Wells’Built Hotel was opened by one of Orlando’s first African American physicians; for a time, it was the only lodging in Orlando that served Black travelers. Photo: Ebyabe/Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

After being abandoned for 25 years, the Wells’Built Museum—which displays memorabilia of Orlando’s African American community and the civil rights movement as well as African art and artifacts—opened in February 2001, in celebration of Black History Month. “This is my calling,” says Thompson, “I’ve been given the privilege to share this information. There are so many stories that have been obscured and omitted, and they need to be brought to the forefront.”

Dr. Jocelyn Imani, TPL’s director of Black History and Culture, says good preservation work “goes down to the individual players, individual people.” TPL is creating a national mosaic of stories, but it’s “hyperlocal pieces” like the Wells’Built Museum that make up the greater narrative.

And it’s not just the interior of the hotel that holds meaning: the Wells’Built’s geography tells a racial story, too. “Like in so many other cities in the United States,” explains Abberger, “the interstate cuts right through downtown—on one side you’ve got the white, affluent, old Orlando, and on the other side is Parramore, which, like many African American urban areas, has suffered from years and years of disinvestment.” And Parramore is bordered to the east by South Division Avenue, a street “long associated with the dividing line between white and Black Orlando,” according to the Orange County Regional History Center.

Thompson’s favorite part of the collection? Dr. Wells’s ledgers, which were discovered in his former home. Also slated for demolition, the house was saved and relocated next to the museum (and will eventually become part of it). “The Wells’Built was one of Ray Charles’s favorite places,” says Thompson, pointing to a record of the venue’s performers and guests. “He would come into the building, register for his room . . . climb the stairs to the second floor, and enter the hallway. He would turn left, and he knew that when he ran into the wall, his room was right there to the left. We know when he was there and when Louis Armstrong was there. That’s one of my favorites because those books were intact.”

Jeff Rupert mentions the ledgers, too: “It’s incredible seeing some of the legendary names on there,” he says. “Count Basie and Duke Ellington, Louie Armstrong—a lot of important vocalists. Count Basie’s band was the first band I ever heard when I was 10 years old,” he adds. “To me, the Wells’Built is as vital as going to Beethoven’s house in Bonn or Wagner’s home in Lucerne. It’s really important. This is a profound place. This is America’s music.”

Beyond the stack of ledgers, exploring the museum feels like walking through a Black history textbook—a raw, honest textbook. Many displays are inspiring: paintings by Floridian Odell Etim depicting performers and crowds at the South Street Casino; an epic panoramic photo of an early African Methodist Episcopal (AME) gathering in Chicago; or a plain white shirt covered in campaign buttons for Thompson, Reddick, Jesse Jackson, and Barack Obama. But much is hard to take in, such as countless “mammy” figurines depicting a toxic stereotype of Blackness.

“You feel this sense of heaviness,” says Teneal, “but then you also feel a sense of freedom.” Expressing gratitude for the people and stories represented by the museum, she adds, “As a Black woman, they’ve given me the opportunity to have a better life.”

At the time of the Chitlin’ Circuit, this was no easy feat. But musicians, like weeds, are also tenacious—hard to keep down. Teneal, who’s opened for Wells’Built lodger B.B. King, agrees: “That’s the thing about music,” she says. “It kind of chooses you. If you don’t do it, you may not die a physical death, but you die inside. So I can imagine that drive in them. It’s probably what made them brave enough to actually just push forward and keep doing it.”

Amy McCullough is senior writer and editor for Trust for Public Land and managing editor of Land&People magazine. She is also the author of The Box Wine Sailors, an adventure memoir.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.