As a girl, Yesenia Garcia loved tooling around on a bicycle in her hometown of Greeley, a plucky city in the high-desert country of northern Colorado. A recent graduate from the University of Northern Colorado, she now finds herself drawn to the burgeoning sport of mountain biking. There’s just one problem: she has no place to go.

To be sure, Greeley residents must now drive at least 30 miles to access a place for mountain biking. Others are hard-pressed to find local spaces where they can simply immerse themselves in nature. But a new conservation project called Shur View will change that. With nearly 1,000 acres of native grasslands, sagebrush, and gulches on the outskirts of the city, Shur View has the potential for many miles of multiuse trails.

“I never really imagined something like Shur View right here in Greeley,” explains Garcia. “It’s something you’d see in the mountains—with hills and trees.”

Perhaps more than any other green space, trails have a remarkable power to connect. In cities, suburbs, and remote rural areas, trails bring us into contact with new vistas and landscapes, whether a mountain peak or cascading stream, a skyline, or a historic monument. They bring us in touch with each other, our neighbors, and our communities—connections that have atrophied due to the pandemic and the pressures of present-day society. And trails put us in touch with ourselves. “On a trail, you’re the same person at the end of the day, but you are a better version of yourself,” says Paolo Perrone, a former TPL project manager in Southern California for Trust for Public Land. “I think trails are sort of the connective tissue between the places we care about. They are a fundamental connection to our landscape.”

Rising temperatures, bigger storms, and asphalt schoolyards pose significant risks during recess. Urge Congress to prioritize schoolyards that cool neighborhoods, manage stormwater, and provide opportunities for kids to connect with nature today!

For five decades, Trust for Public Land has worked to create, expand, and protect trails across the United States. Our work has spanned iconic National Scenic Trails, mountain networks, suburban greenways, rail trails, and urban paths. Creating a trail or trail system is a complicated endeavor, involving numerous landowners and agencies, and it can take years, if not decades. But we recently committed to protecting an additional 1,000 miles of trails because we recognize that they have the power to address a number of urgent problems afflicting communities and society at large. Trails improve public health by encouraging people to get out and move. They jumpstart ailing rural economies with a new focus on recreation and ecotourism. And trails can mitigate climate change by encouraging people to ditch the car—and tailpipe emissions.

Trails are where communities come together. In an ever more disconnected world, trails are where joggers and cyclists share routes with dog walkers and hiking families, where plants and wildlife flourish, and where we all feel a little more at ease as we breathe the fresh air. We’re connecting over 3 million people to 1,000 miles of trails across the country, bringing them closer to nature and each other.

You can help connect people to nature by sending a letter to your members of Congress today in support of bills that will expand our country’s trails and access to nature.

Dollars and Sense: Making the Most of Federal and Local Infrastructure Investments

J.T. Horn, director of Trust for Public Land’s national Trails initiative, says the moment is ripe to scale up work on trails, which includes protecting the lands around them. Because of development pressures, many existing trails are losing the buffers of land that historically gave them a wilderness feel. And thanks to new federal funding, like the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, with its many climate provisions, the resources are there to help towns, cities, and nonprofit organizations undertake trail projects.

“There’s $1.4 billion—with a B—in new trails money in the [2021] infrastructure bill adopted by the Biden administration,” Horn says. “That’s super exciting and we need to be able to tap into that and also help other trails groups across the country access that money.”

Trust for Public Land is well positioned to be the bridge between, say, a community group, which understands the needs on the ground, and a large transportation agency, which holds the purse strings and permitting power.

“It’s a lot about community engagement and design work,” Horn explains, pointing to recent trail initiatives from the Klamath Basin in Oregon to Florida’s Gulf Coast. “With big projects, we try to get things shovel ready.”

Although Trust for Public Land is not and has never been a trail-building entity, increasingly, TPL is sticking around after the land is acquired and conveyed to a nonprofit group or parks agency. “A lot of times in the past, we would record the deed and walk away,” Horn adds. “We want to change that. We are not going to have a TPL trail crew, but we can activate these properties to enhance our land protection and solidify new partnerships.”

That might include creating trails where none exist; installing trailhead infrastructure such as parking, kiosks, signs, and toilets; and building such recreational amenities as campsites, cabins, and boat launches.

Trails Connect Existing Public Spaces to Expand and Broaden Outdoor Access

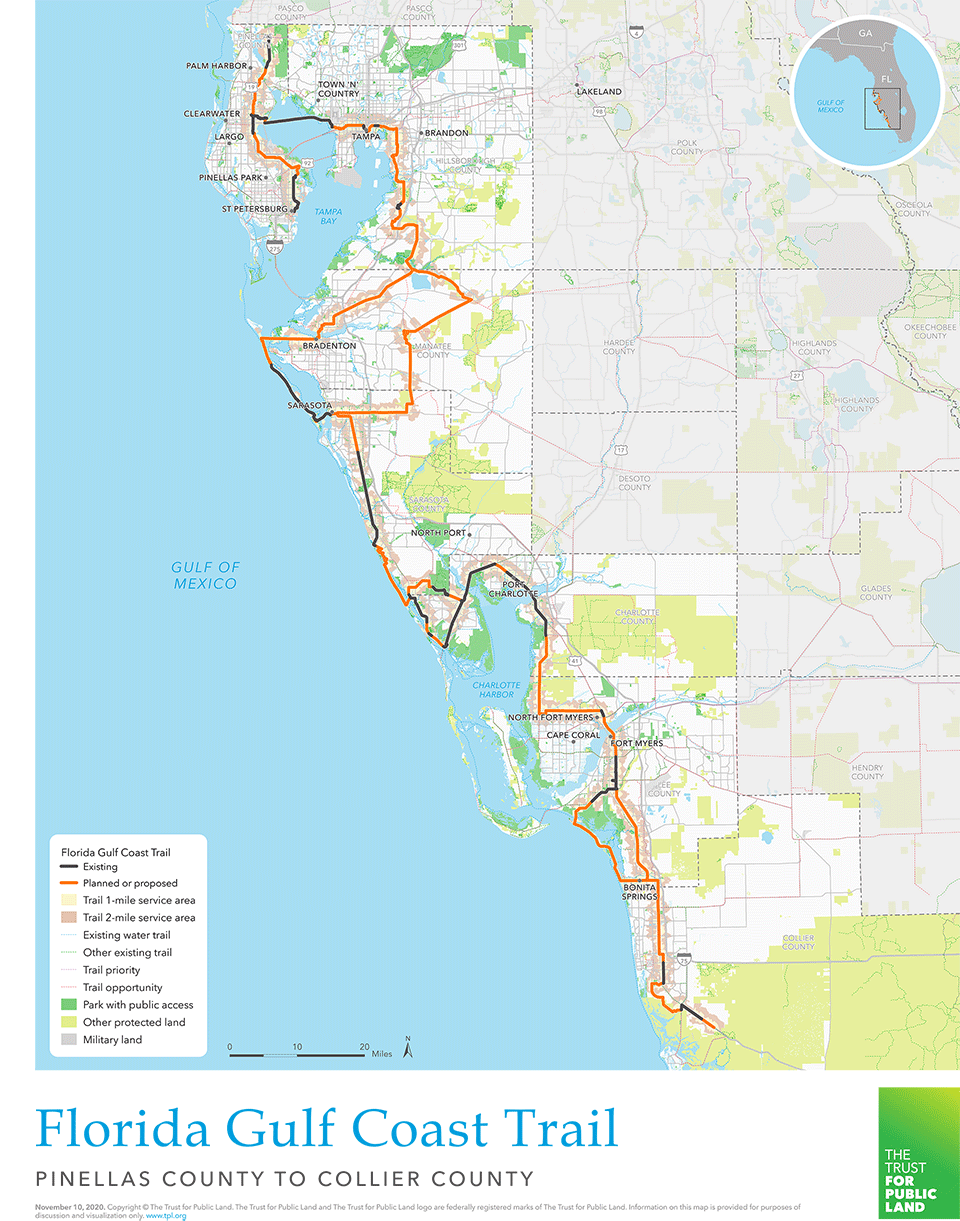

In Florida, where Trust for Public Land is working to make the proposed Gulf Coast Trail a reality, a key partner is the Friends of The Legacy Trail. Since 2008, Louis Kosiba, the group’s president, has overseen development of an 18-mile multiuse trail in Sarasota County, called the Legacy Trail. The last segment was completed in March.

Eventually, the idea is to connect the Legacy Trail, now a county park, to other existing trails across eight counties, from Tampa to Naples, and then fill in the gaps. The result: a 300-mile Florida Gulf Coast Trail. “This is a beautiful geographic area, with bays and forests and wetlands, and people would love to bicycle through it,” Kosiba allows. “Florida is a big cycling state. It’s easy to cycle here because there aren’t any hills.”

Dog walkers, joggers, families, roller skaters, and those with limited mobility are also eager to explore the region via trails, according to Charles Hines, TPL’s Florida Gulf Coast Trail program director. He says about a third of the planned 300-mile-long trail is finished. He is now working with the state and groups like the Friends of The Legacy Trail to refine the route to take advantage of existing parks and agricultural open space.

Hines, a former Sarasota County commissioner, is confident the full Florida Gulf Coast Trail will eventually come together. “Trails are funny,” he says. “They are the one thing everyone agrees on. Whether you are an environmentalist or a developer or a business owner, you can find in a trail system something that’s beneficial to you.”

Even Major Networks and Iconic Scenic Trails Have Gaps, Putting Key Access Points at Risk

Some 1,500 miles north, Trust for Public Land is busy filling in gaps and expanding three major trail networks in Vermont—the Long Trail (used mainly by hikers), the Catamount Trail (a favorite of cross-country skiers) and the Velomont Trail (a mountain bike destination). These are collectively referred to as TPL’s Green Mountains program.

Begun in 1910, the Long Trail unfolds north to south along the spine of the Green Mountains. Though completed in 1930, the 273-mile trail includes areas that lack permanent public access, with 6 miles remaining that are not legally protected. Those last miles are scattered across a dozen or so private properties whose owners currently allow hikers to cross their land.

The fear is that a future owner might shut down or revoke that access, forcing users to make unwieldy detours on roads. This is the case even on some of the country’s most iconic scenic trails, such as the Pacific Crest Trail, where the majority of the route is on protected public land, but several sections remain on private lands and are thus vulnerable to closure. Of the 30 National Scenic Trails and National Historic Trails designated by Congress, only the Appalachian Trail is completely protected. Even on the A.T. there are many side trails and viewshed parcels still at risk.

In Vermont, Trust for Public Land has worked with the Green Mountain Club for over two decades to ensure permanent public access to the remaining private segments, both through land acquisitions and conservation easements. We have also protected large swaths of land on either side of the trail.

A family takes a hike along a trail near Rolston Rest. Photo: Kurt Budliger

Shelby Semmes, TPL’s New England director, notes that conserving the lands that flank trails is “an important way to protect climate-resilience corridors in the state.” Unfragmented natural landscapes reduce flooding and lower temperatures while preserving migration paths for wildlife.

Kate Wanner, TPL’s senior project manager in Vermont, agrees. “We have done a number of projects that address the fact that 100 feet on either side of the trail was protected, but nothing beyond that,” she explains. “We want to really preserve the wilderness experience.”

Two recent conservation projects—Lincoln Peak and Rolston Rest—do just that. Encompassing 2,800 acres of forests, streams, and scenic peaks, the Rolston Rest property hosts miles of both the Catamount and Long Trails and even includes the new Velomont Trail. Lincoln Peak conserved 619 acres, including 1.34 miles of the Catamount Trail and a buffer around the Long Trail. In late 2022, the so-called Judevine Headwaters project, undertaken with the Green Mountain Club, added 14 acres to Long Trail State Forest and guaranteed permanent public access to another missing link in the Long Trail. A trailhead parking lot is also planned. See a map of Rolston Rest.

Mike DeBonis, executive director of the Green Mountain Club, which has 10,000 members, said working with Trust for Public Land has yielded positive synergies across trail networks. “TPL has the horsepower—the staff and expertise—to handle these larger real estate transactions and maximize the conservation potential,” he points out. “That’s a benefit not only for us, but other organizations in the state that partner on these projects.”

Cutting Climate Emissions with Every Pedal Stroke—Trails Give Communities Green, Safe Transportation Routes

East of New York City, on Long Island—a collection of communities long considered the quintessential picture of suburban life—Trust for Public Land is working to create the new Long Island Greenway, extending from Manhattan to Montauk, the island’s easternmost town. The impetus, to some degree, was the success of the new Empire State Trail, which stretches north from New York City to Canada and west from Albany to Buffalo.

“The Empire State Trail was an amazing project, but [it stops] in Manhattan,” argues Carter Strickland, former New York State director and vice president for the mid-Atlantic region at Trust for Public Land. “But about a third of state residents live east of Manhattan, on Long Island.”

Trust for Public Land is now focused on a 25-mile central section that would straddle Nassau and Suffolk Counties—from Eisenhower Park to Brentwood State Park. We recently commissioned a feasibility study for that segment and are set to start work on a conceptual design. Read our Long Island Greenway 2020 Report.

Another motivation for the Long Island Greenway was climate change. The car is king on Long Island, and parkways and expressways are routinely choked with traffic, spewing carbon dioxide (the main greenhouse gas behind climate change) into the air.

Yet another concern is safety. According to Strickland, the two counties that make up Long Island lead the state in car accidents involving bicyclists and pedestrians. Marty Buchman, owner of the Stony Brookside Bed and Bike Inn, knows firsthand how hazardous biking on the island can be. In 2017, when he was teaching in a nearby public school, he was struck by a car during “Bike to Work Day.” In 2022, he was hit again. He broke bones in both accidents and had the right of way in both instances.

But for Buchman, whose inn caters to bicyclists, the need for a greenway transcends concerns about any one issue. Rather, it is fundamental to our self-conception as a society. “We can’t keep depending on the car,” says Buchman, advocacy director for the Suffolk Bicycle Riders Association and board member of the New York Bicycling Coalition. “This would be so beneficial for green tourism and economic development. Young people are looking for places where they don’t need cars.”

The first 25-mile segment of the Long Island Greenway would largely piggyback on power line rights-of-way, allowing the greenway to avoid having to zig and zag around homes and businesses. “The power lines are such a gift,” Buchman adds. “It’s the only real alternative.” Similarly, defunct railway routes are existing, often undeveloped and unbroken corridors ripe for repurposing into community trail systems. The Ventura River Parkway in California is one example of the growing rail-to-trail movement across the country.

Seeking Local Input Makes Trails Inviting and Accessible to the People Who Want, Need, and Use Them

Across the country, in the city of Greeley, Colorado, Trust for Public Land recently helped protect the 975-acre Shur View property. The acquisition effectively doubles the amount of natural area available to the 109,000 residents of Greeley, whose population has more than doubled since 1980.

Shur View borders the Cache la Poudre River and offers spectacular views of the Rocky Mountains and northern front range. With community input, the plan for the new park calls for at least 17 miles of mountain bike trails that can also be enjoyed by hikers. With a quarter of residents living in poverty, the city is poised to reimagine its economy.

“With Shur View, Greeley has the potential to be a regional destination for mountain biking in particular,” says Emily Patterson, managing director of TPL’s Parks for People program in Colorado. “But the trails will be designed for all types of users. There will be those really cool mountain biking trails, but there will also be places where a family can walk and just enjoy the open space or where an elderly person can enjoy an accessible spot.”

In August of 2022, a design team began the process of creating master plans for both Shur View and a community green space, called Delta Park, on the eastern side of Greeley. Throughout 2022, TPL engaged the immigrant and refugee communities surrounding Delta Park to learn what residents want from their park, which currently has few amenities and very little shade. Some of those same community members will be enlisted to provide input on Shur View.

“Usually with a natural area like this, you’re going to get community input, but it will be from people who are adjacent to the property or people with free time and money,” observes Wade Shelton, a senior project manager at TPL. “But we are going to take folks from the Delta Park neighborhood whom, normally, no one would shuttle over to see Shur View—but we are. Greeley has already put in for a new bus stop right at this property, so folks who have no [other] way to get there can access it.”

Patterson adds that TPL is striving to make the community engagement process as attractive as possible. “We want to build that capacity and leadership at Delta Park so we can then say there is an exciting opportunity just 25 minutes from your door,” she says. “This is an opportunity for you to have a voice in what happens to Shur View. This community has a lot on their plate in terms of other priorities and needs. You have to make it as easy as possible for them to show up—giving stipends to potential panelists, providing transportation, bringing people in at the beginning and not just as an afterthought.”

One such community member is Garcia, who is also a Trust for Public Land “resident expert” at Delta Park, which is down the street from her home. She has visited Shur View once so far and looks forward to accessing the property, as do her friends and neighbors, she says.

“Shur View is a beautiful space, and it’s close by,” explains Garcia, who emigrated to Colorado from Mexico when she was 5. “I do ride my bike around where I live in Delta Park, but I prefer to be outside in nature.”

Rural Communities Are Reinforcing and Even Reinventing Their Local Economies on the Strong Back of Trail Infrastructure

Farther west, at Spence Mountain in Oregon, a private landowner has allowed the community to create and use 50 miles of trails on 7,500 acres over the past decade. “As it got more popular and people started using it, there was a conversation about what happens if this property changes hands—after all of the investment in trails,” says Kristin Kovalik, TPL’s Oregon program director.

TPL has worked with the Klamath Trails Alliance and other partners to buy the property; a closing is expected by the end of 2022. Klamath County will then take possession of the land, while the Klamath Trails Alliance, which built the trails on Spence Mountain, will continue to maintain the trail network.

Protecting the Spence Mountain property, which was appraised at $6.2 million, will strengthen the recreation economy of nearby Klamath Falls, while providing an outlet for local residents. According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Klamath County was ranked last in Oregon for health outcomes in 2021.

“There is definitely an eye on what we need to be doing to help people get outdoors and have places close to home to exercise,” Kovalik notes. Already, a community-run youth mountain biking team, called the Jackalopes, can be seen zipping down the mountain on weekends.

Drew Honzel, who helped found the Klamath Trails Alliance, says the group plans to blaze another 15 miles of trails on the property. With an elevation change of about 1,700 feet, Spence Mountain is ideal for mountain biking and hiking, and the scenery doesn’t hurt. Laced with pine, fir, and cedar trees, the mountain is surrounded by Klamath Lake on three sides. “You get views of the water the higher you go,” he says.

“We used to see all these people driving right past Klamath Falls from California headed to Bend and Oakridge,” he adds. “We thought we should be able to peel some of those people off to spend a day or two in Klamath Falls. And that has happened.” A recent marketing study found that Spence Mountain averaged 57,000 visits a year over the past three years. A fifth of those visits, Honzel said, were by nonresidents who contributed $2.6 million to the local economy and supported 43 travel-related jobs.

Spence Mountain’s Recreation Economy

Perhaps the growing popularity of trails speaks to a deep-rooted desire for authenticity and simplicity in our frenetic, modern world. “I think we go on trails thinking that the trail transforms us and we come out realizing that’s who we were all along,” declares Liz Thomas, a professional hiker who has put one foot in front of the other in both cities and rural areas, in the United States and around the globe.

The author of Long Trails: Mastering the Art of the Thru-Hike, Thomas adds: “When we strip away our jobs and our cars and our clothes and all of these sort of preconceived notions we have about ourselves and just go out there and be—that’s who we are.”

Lisa W. Foderaro is a senior writer and researcher for Trust for Public Land. Previously, she was a reporter for the New York Times, where she covered parks and the environment.

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.