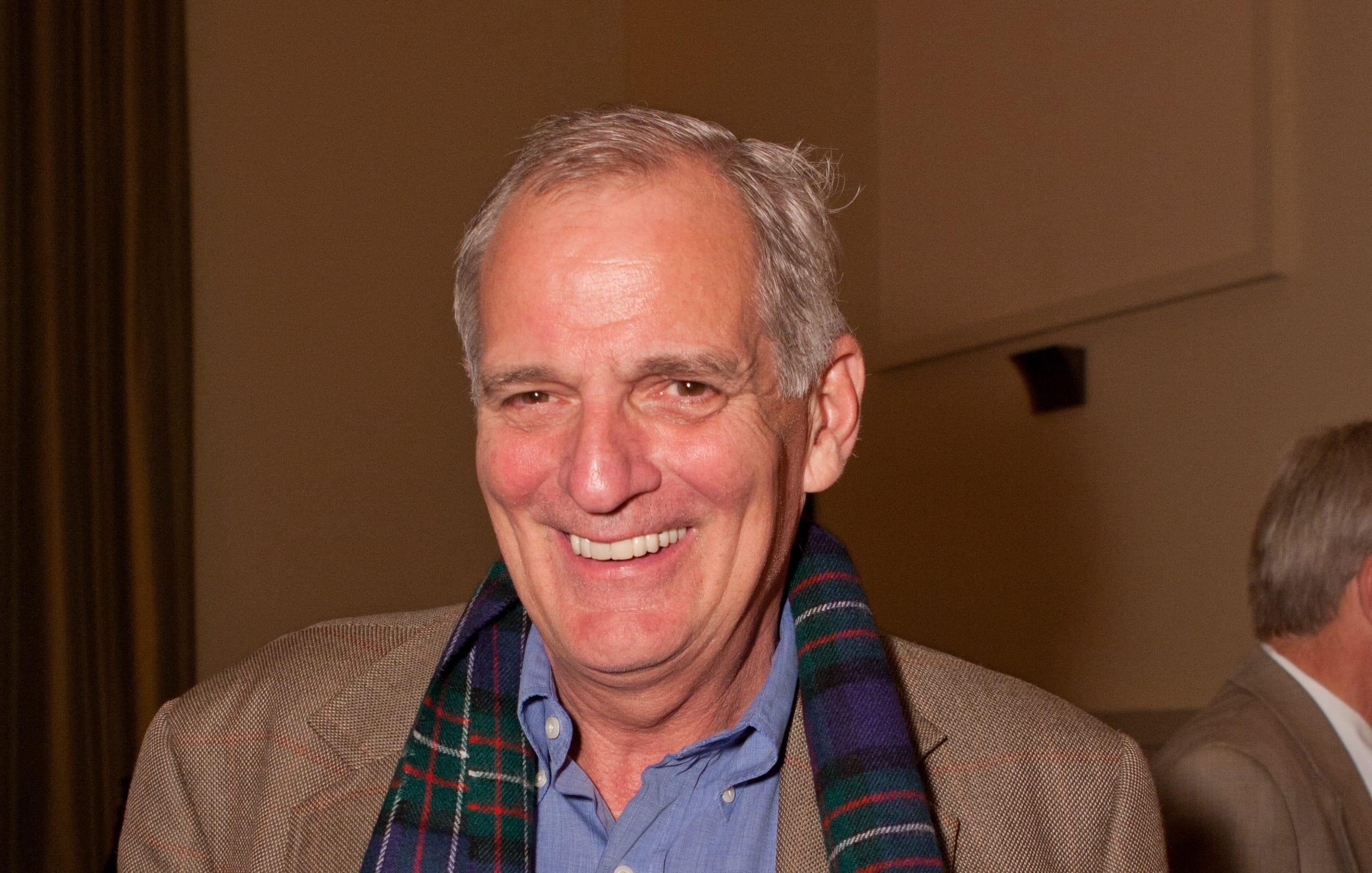

Welcome Howard Frumkin, Our Newest Senior Vice President

Welcome Howard Frumkin, Our Newest Senior Vice President

As wildfires, hurricanes, and a global pandemic continue to upend lives, the role of our environment—the places in which we live, work, learn, and play—in our personal and community well-being is clearer than ever. So are the links between global processes, such as the changing climate, and local, on-the-ground realities. And so are the many disparities in our society, making some of us far more vulnerable than others to illness and suffering.

Dr. Howard Frumkin, an international leader in planetary health and professor emeritus, environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington, will join us beginning September 27 as senior vice president. He believes that TPL’s path forward can be mapped by linking land with health, equity, and climate action—harnessing “the power of land for people” through community-centered and evidence-driven approaches.

[How well is your city meeting the need for parks? Explore the 2021 ParkScore rankings.]

With Dr. Frumkin’s leadership, we’ll establish an institute that will generate evidence through collaborative, innovative research—drawing on multiple disciplines and a collaborative approach—and propel that evidence into action through programs, policies, and advocacy, on a national scale.

The author of more than 300 scientific journals, chapters, and books, including textbooks on general environmental health, planetary health, and the built environment. Dr. Frumkin’s latest title, Planetary Health: Safeguarding Human Health and the Environment in the Anthropocene, co-authored by Andy Haines, launches Sept. 14, 2021.

We sat down with Dr. Frumkin to learn more about him and his vision for the institute.

Can you explain the concept of planetary health; what does it mean, and how did it come about?

Planetary health is the health of human civilization and the state of natural systems on which it depends. We live on a very different planet than the one our grandparents inhabited. We’ve disrupted numerous planetary systems: we’ve altered the climate; we’ve reduced biodiversity; we’ve disrupted cycles of water, nitrogen, and phosphorus; we’ve transformed land cover and impoverished soils; we’ve contaminated the planet with pollutants that linger for many years. Planetary Health is about understanding and acting on these global-scale challenges, across disciplines and institutional boundaries. Although the challenges are global, the responses are often very local. The approach of planetary health is people-centered, systems-based, upstream-facing, equity-committed, future-oriented, solutions-driven, and hope-inspiring.

“Very strong evidence exists that green energy, well-designed cities, healthy diets, and green chemistry all contribute to better, healthier lives,” says Dr. Howard Frumkin, who joins Trust for Public Land Sept. 27, 2021, as senior vice president.

“Very strong evidence exists that green energy, well-designed cities, healthy diets, and green chemistry all contribute to better, healthier lives,” says Dr. Howard Frumkin, who joins Trust for Public Land Sept. 27, 2021, as senior vice president.

Your two recent books on Planetary Health, one subtitled “Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves” and the other “Safeguarding Human Health and the Environment in the Anthropocene,” talk about the importance of planetary health and our future. How would you characterize this Anthropocene era that we’re in?

Human activity has altered the planet so dramatically that geologists have recognized a new geological epoch, shifting from the Holocene, the 12,000 or so year-long epoch in which civilization as we know it emerged, to the Anthropocene, or the epoch characterized by human domination of many of Earth’s systems. This isn’t just a geological concern. We depend on a stable planet for every dimension of our lives. The challenge of the Anthropocene is to achieve and maintain sustainable ways of living—which means a significant course correction from our current trajectory.

The global scale of our current climate, health, and equity challenges feels daunting and overwhelming. How important is maintaining a sense of hope in the face of this climate emergency?

It’s true – these planetary trends are grim. Despair is an occupational hazard for anybody who’s paying attention to contemporary planetary changes. But we need to fight despair. Despair is immobilizing, it’s painful, and it doesn’t accomplish anything – at a moment when we need to be accomplishing a lot. We need to embrace hope ourselves, and inspire hope in others. Very strong evidence exists that green energy, well-designed cities, healthy diets, and green chemistry all contribute to better, healthier lives. We’re seeing major advances in technology, policy, and private sector initiatives. Wind and solar are now cheaper sources of electricity than fossil fuel in most places. More and more countries and companies are making net zero commitments. Activism is blossoming, led by a generation of diverse, politically savvy young people. Public opinion is changing; more than half of Americans are “extremely” or “very” sure that global warming is happening. Despite the pronouncements of some naysayers, there is no evidence that we’ve lost this fight. There is every reason to maintain hope.

What attracted you to join Trust for Public Land? How might your vision for a new institute further catalyze communities that are healthier, more livable, and more equitable?

Public land is a powerful, cross-cutting framework. From the small scale of a green schoolyard to the large scale of a wilderness reserve, wise and equitable land stewardship is a pillar of great communities, a strategy for health, social connectedness, equity, climate action, and long-term sustainability. Trust for Public Land truly understands the interconnectedness of these issues, and the many strategic opportunities they offer. Not only that, TPL has an extraordinary track record of community partnership and of grounding its work in solid evidence.

You’ve referred several times to TPL’s commitment to health, equity, and climate action in its mission. How does TPL’s commitments fit into the global context?

While TPL’s strategic plan includes commitments on each of these issues, it exists in a still broader context—what the resilience funders network Omega calls “the global polycrisis.” This refers to the intersection of biosphere stressors, societal stressors, and technology stressors. In particular, TPL’s strategic priorities need to be advanced in the context of contemporary social and political dysfunction: profound political polarization; declining social capital; rising income and wealth inequality; loss of public faith in government, science, and even the very concept of truth; and toxic disinformation spread widely on social media.

Of course, no one organization can tackle every challenge. But we need to be aware of the broader connections of our work, we need to be systems thinkers, we need to be skeptical of artificial boundaries, we need to cultivate robust partnerships, and we need to embrace solutions that are complex and sometimes indirect.

I believe that a collateral benefit of TPL’s work could be bridge-building across some of the divides that bedevil our country at the moment. There is widespread agreement across the political spectrum on the value of our natural heritage. I see a “meta-goal” of the Institute’s work as seizing opportunities to leverage that agreement to heal some of the nation’s rifts. Greater social solidarity is not only an intrinsic good, it will also help advance TPL’s goals of health, equity, and climate action.

The conservation community has criticized as too male, too white and too exclusive. We see that reflected in access to nature heavily weighted to Caucasian communities—and TPL is working to change that. What’s your approach to these issues?

All of our leading institutions, including nonprofit groups, need to reflect our diverse society. This is both a matter of simple justice, and a prerequisite to success. As a “pale, male, and stale” person, I recognize the privilege I have, and my responsibility to be actively anti-racist. I plan to use my position as an opportunity to help expand the diversity of TPL’s leadership. From Day One, I’ll be thinking in terms of succession planning, supporting and mentoring younger colleagues from under-represented groups. Building a strong, diverse bench of future leaders is a top priority for me.

In our work, equity must be central. This extends from the ways in which we partner with communities, to the kinds of research questions we ask, to the kinds of knowledge we honor, to the policy solutions we advance. Just as we can’t have healthy people without a healthy planet, we can’t have thriving communities that aren’t fair and inclusive.

Rising temperatures, bigger storms, and asphalt schoolyards pose significant risks during recess. Urge Congress to prioritize schoolyards that cool neighborhoods, manage stormwater, and provide opportunities for kids to connect with nature today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.