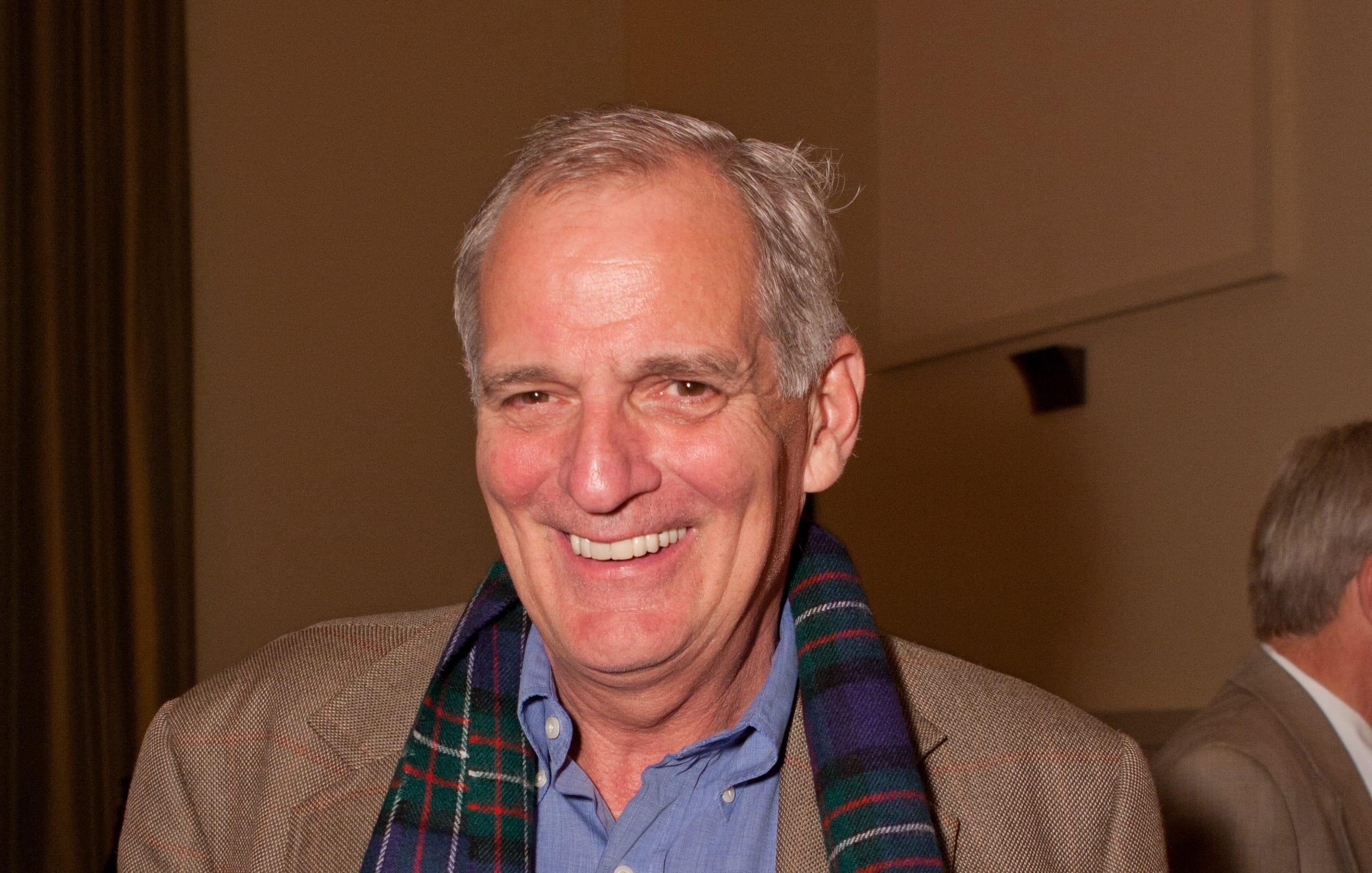

Get to know Phil Ginsburg, city park innovator

Get to know Phil Ginsburg, city park innovator

A New York magazine story posing the question “Is San Francisco New York?” recently made media waves. While the piece focused on high tech business and real estate, a more interesting comparison might have been between the cities’ park systems. Though a surface comparison seems unfair—New York’s park system is seven times larger—a closer look shows that San Francisco’s parks stand up very well to New York’s. In fact, San Francisco may be a national leader among cities for its innovative management and ambitious plans.

At the helm of the San Francisco’s Recreation & Parks Department sits General Manager Phil Ginsburg, a youthful and athletic transplant from the East Coast who went west in 1990, a few months after the Loma Prieta earthquake rocked the area during the World Series. Ginsburg, now 47, has worked both energetically and creatively (first under Mayor Gavin Newsom and then Edwin Lee, Newsom’s successor) to create one of the nation’s top five park systems (according to The Trust for Public Land’s 2013 ParkScoreⓇ index). His out-of-the-box management and innovative approach to public-private partnerships have enabled San Francisco to leverage large amounts of public money approved by voters to both build new parks and improve those which already exist.

Ginsburg seems to have been born to the job. He grew up Merion, Pa., a Main Line suburb of Philadelphia. “After school or after dinner, you went to the parks,” he recalled recently. “Your parents didn’t know or didn’t care where you were.” His main sports were baseball and soccer, and he continued to play them when he went north to Dartmouth College, on the banks of the Connecticut River in New Hampshire. On the picturesque Dartmouth campus, almost in the shadows of a suite of White Mountains—Smarts, Cube, Holt’s Ledge and Moosilauke—Ginsburg discovered another great love.

“Dartmouth was just one gigantic park,” he says, recalling freshman orientation canoeing trips on the Connecticut River, as well as a hike to the Dartmouth Lodge on Mount Moosilauke where they were fed a hearty breakfast of green eggs and ham.

Summer wilderness excursions included an expedition with Outward Bound in Minnesota’s Boundary Waters National Park, and hiking and camping in the Grand Teton and Glacier National Parks.

Ginsburg continued his studies in San Francisco, where he earned a law degree at UC Hastings. After working as an attorney representing municipal labor unions, he joined city government, rising to become Mayor Newsom’s chief of staff. In that job, he mediated an agreement to close a large chunk of a drive through Golden Gate Park to traffic on Sundays, and also negotiated agreements for a major music festival, Outside Lands, in the park. Following a recommendation by the SF Recreation & Parks Commission, Newsom appointed Ginsburg General Manager in July 2009.

Approaching his fifth anniversary in the job, Ginsburg already has one of the longer tenures of a parks boss for a large city, and with his marathon runner’s endurance (he has run 15 of them, including two at just over 3 hours), he is working to make the city’s park system among the best in the world.

What gives SF top scores for parks? For starters, there’s proximity. The vast majority of city residents live within a 10-minute walk of the city’s 220 parks, playgrounds and athletic facilities, encompassing 4,000 acres. And the system is in a golden age—under Mayors Newsom’s and Lee’s enthusiastic leadership, San Francisco voters overwhelmingly approved bonds in 2008 and 2012, authorizing $330 million for capital improvements to their parks.

“Financial sustainability” is a bedrock principle of Ginsburg’s management. One third of his expense budget of almost $140 million comes from earned revenue, which increased from $38.5 million in 2009 to $52.2 million in 2013 (the balance of his expense budge comes from the City’s General Fund and from the Open Space Fund). It was his attention to the bottom line that allowed him to reinvigorate public recreation, taking a division that had been repeatedly cut, and, working with the union, to reinvent recreation to hire staff with a broader range of skills, delivering more and higher quality programs with fewer staff, based on communities making specific programmatic requests. Other innovations included dramatically enlarged “scholarship” programs to make them free or low cost, a youth stewardship program that provides environmental education in 40 public schools, and cultivating nearly 150,000 hours of volunteer labor a year (a $3 million value). And a novel workforce development program trains gardener apprentices, includes advanced horticulture courses at City College of San Francisco, and leads to good, permanent jobs.

As the city’s population increases (it is growing by 10,000 new residents a year), Lee and Ginsburg are committed to keeping it livable for families. In the pipeline are new projects slated for Noe Valley Town Square, India Basin, Francisco Reservoir, and new parcels in the South of Market area. Also about to begin construction is a $13 million upgrade of Dolores Park, a beloved patch of green with spectacular views famous for its vibrant, youthful picnic scene (and recently featured in an episode of HBO’s new hit drama Looking).

Among the arrows in Ginsburg’s quiver is a creative and entrepreneurial approach to public-private partnerships including one with the City Fields Foundation, through which the three Fisher brothers led a $50 million program to install synthetic turf playing fields, a move that allowed a dramatic increase in playing hours while decreasing the need for precious water for irrigation and eliminating the need to rest the fields. In a partnership with The Trust for Public Land, a playground and community center are being rebuilt in the heart of the Tenderloin, San Francisco’s notoriously tough neighborhood.

All is not roses—Ginsburg acknowledges that his budget is probably about $30 million short on an annual basis of where it should be, according to a report by SPUR, a Bay Area planning and good government organization. He especially laments not having enough money to properly care for the 170,000 trees in the parks. San Francisco’s legendary iconoclasm can be on full display in public meetings and hearings, and a recent vote by the City Commissioners to finally put in place overnight closing hours was marked by rancorous debate. Ginsburg cites “the difficult task of balancing the use of public space between intense active use and the need to protect and keep green space environmentally sustainable.”

But through it all, Ginsburg sees a greater public good that is worth fighting for, manifested in the city’s expansive view of parks.

“True environmentalism is premised on maintaining urban density,” he says, seeing that “parks will be more and more critical to the health and vitality of the city. Parks must be affordable, and access equitable, and we have a particular responsibility in underserved areas—where parks play a literal life-saving role.”

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.