Cue the Canoes: Quiet Waters in a Cacophonous World

Cue the Canoes: Quiet Waters in a Cacophonous World

Summer is the ideal time to get out on the water. But sometimes, spending the day on a nearby lake or pond can feel more like running a gauntlet, what with Jet Skis and motorboats ripping across the tranquil surface, generating intimidating wakes and noise in the process.

Motorized watercraft can be thrilling, no doubt. But there is something especially relaxing about a water body open only to kayaks, canoes, and electric boats.

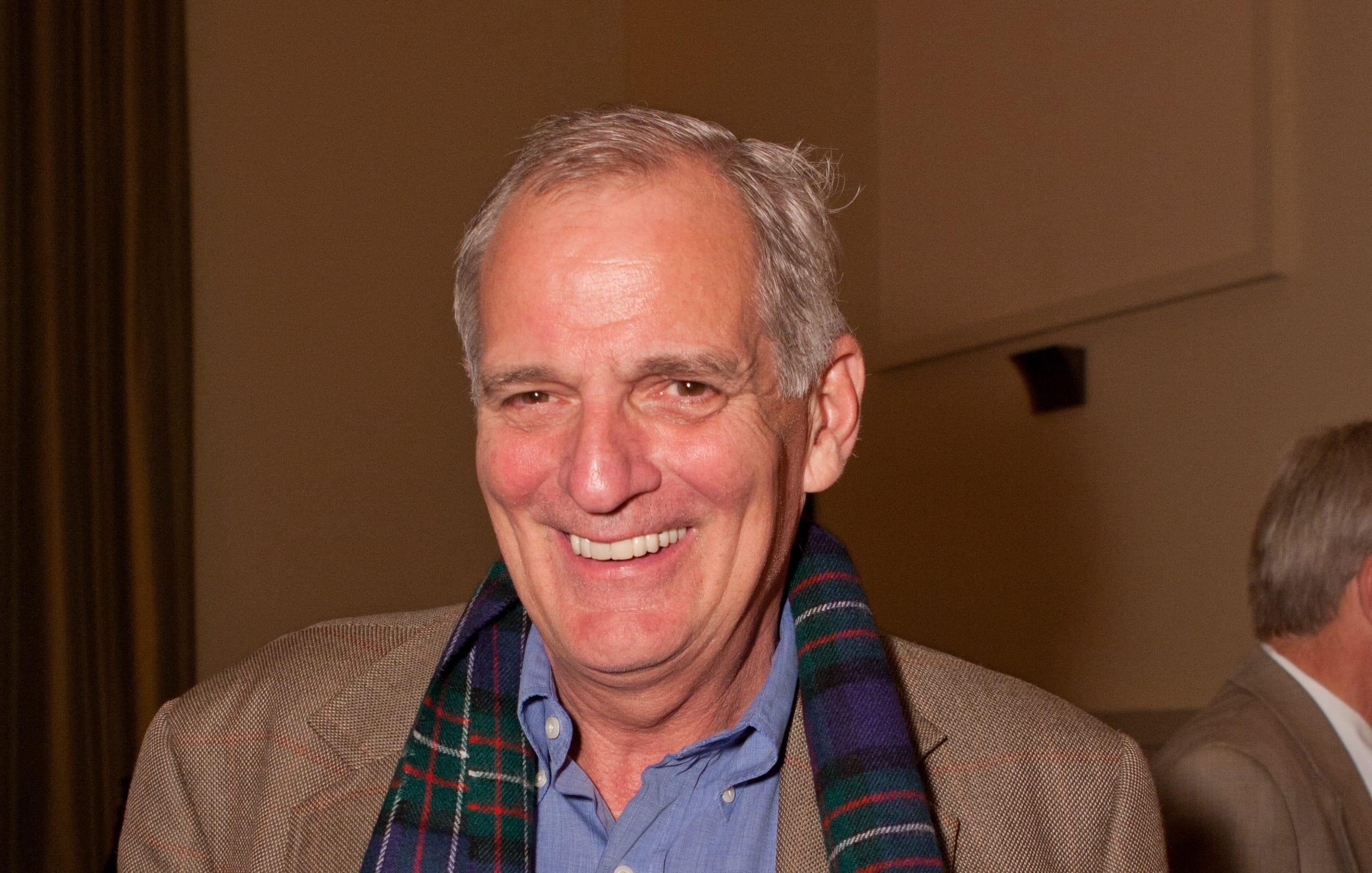

“Water covers 70 percent of the Earth’s surface and makes up 60 percent of our bodies,” says Jim Petterson, Trust for Public Land’s vice president for the Mountain West region and Colorado and Southwest director. “We have this innate biological connection to water. The mere sight or sound of water induces a flood of neurochemicals, all good for wellness—mental and physical. Motorized use has its place, but motors have impacts on people and wildlife and on natural systems.”

In recent years, TPL has protected lakes and ponds from Vermont to Colorado that are designated quiet zones. One of our recent conservation projects included Willow Bay in Adams County, outside Denver. Trust for Public Land teamed up with the county to purchase the 174-acre Willow Bay property in 2017 for $9.1 million. Part of the South Platte River Corridor, the land includes a 110-acre lake, which will prohibit motorboats when it opens to the public within the next two years, after completion of a master plan.

Trust for Public Land has worked to preserve areas along the South Platte River, such as Willow Bay, for more than 30 years.Photo credit: JoAnne Clarke

Trust for Public Land has worked to preserve areas along the South Platte River, such as Willow Bay, for more than 30 years.Photo credit: JoAnne Clarke

For Wade Shelton, a senior project manager for Trust for Public Land, Willow Bay’s proximity to Denver made its protection all the more important. Too often, paddlers and others have to venture far away from cities and suburbs into rural areas in order to find quiet waters where they can put in a canoe or kayak.

“At the end of the day, your quality of life is what’s close to where you live,” he explains. “This conservation deal was something that ensures people have access to a wilderness-type experience without having to travel far.” Shelton is now working with the county and a private landowner on a second acquisition, which would expand protection and public access at the lake.

A growing body of research has underscored the negative effects of noise and artificial light on wildlife. The impacts interfere with everything from attracting a mate to finding food. Writing in The Atlantic this summer, Ed Yong declared, “We have distracted [animals] from what they actually need to sense, drowned out the cues they depend upon, and lured them into sensory traps. All of this is capable of doing catastrophic damage.”

Shelby Semmes, Trust for Public Land’s vice president for the Northeast region, believes protecting lands and waters where people can tap into nature’s healing qualities is more vital than ever. “We need to experience stillness in our lives,” she says. “Having places where we can go to escape the din of engines, screens, and all the rest is really important—for people, as well as for animals.”

Serene water beckons paddlers to Lake San Cristobal, the second-largest natural lake in Colorado.Photo credit: M4 Ranch Group

Serene water beckons paddlers to Lake San Cristobal, the second-largest natural lake in Colorado.Photo credit: M4 Ranch Group

Another project in Colorado that features nonmotorized access is Lake San Cristobal in Hinsdale County. The second-largest natural lake in the state, San Cristobal was formed several centuries ago when a landslide dammed a fork of the Gunnison River. The 2-mile-long lake and shoreline are owned mainly by Hinsdale County and the Bureau of Land Management.

Until recently, the primary access point was via a county-owned dock. During the pandemic, however, as visitors thronged the high-alpine lake, the juxtaposition of motorboats and paddleboarders grew increasingly fraught. The lakeshore also lacked a good spot for families interested in picnicking or wading.

But that has recently changed. Trust for Public Land worked with Friends of Lake San Cristobal and Hinsdale County to acquire a 10-acre peninsula and island on the lake from a private landowner. A grassroots fundraising campaign garnered $200,000 toward the $1.5 million purchase price in less than a month.

Now there is a new approach to the lake for those seeking a more serene experience. Low-horsepower motors are still permitted on the water, but the newly protected access is set aside for human-powered boats and boards. In addition, in May the county imposed new regulations that ban Jet Skis and waterskiing. “We are moving toward a quiet lake,” says Kristine Borchers, a county commissioner in Hinsdale County.

Colorado Governor Jared Polis appeared at the Lake San Cristobal opening celebration on July 13, saying, “We are rapidly making Colorado’s outdoor attractions easier and less expensive to access.”

“The lake is in the heart of the San Juan Mountains and it’s spectacular,” adds Petterson. “One access point was not sufficient for the demand. The county said we need a place where nonmotorized users like paddleboarders, kayakers, and canoes can go. This place is perfect because the peninsula creates a protected cove.”

Embarking for a calm day of kayaking at Mud Pond in Granby, Vermont, another body of quiet water.Photo credit: Jerry and Marcy Monkman

Embarking for a calm day of kayaking at Mud Pond in Granby, Vermont, another body of quiet water.Photo credit: Jerry and Marcy Monkman

On the other side of the country, a flurry of conservation projects extending from Maine to Vermont and New Hampshire has centered on water bodies where the use of motors is either impractical or banned by local ordinance. One such project is Robb Reservoir in Stoddard, New Hampshire, a 1,670-acre property in the southwestern corner of the state. In 2008, Trust for Public Land helped protect the land, which includes a 150-acre reservoir; the property is now owned by the Harris Center for Conservation Education, and its waters are used only by paddlers and electric boats.

The peaceful property almost eluded the grasp of conservationists, however. In the 1990s, an 82-lot housing development was planned for the banks of the reservoir. But the area’s nature beauty and robust mix of wildlife habitat led to a surge of community activism. Guided by Trust for Public Land’s expertise in conservation finance, activists and partners saved the property, which also includes the North Branch of the Contoocook River.

Lily pads thrive at Robb Reservoir, a body of water that is off-limits to motorized craft.Photo credit: Jerry and Marcy Monkman

Lily pads thrive at Robb Reservoir, a body of water that is off-limits to motorized craft.Photo credit: Jerry and Marcy Monkman

At the time of the protection, Rodger Krussman, TPL’s director of field operations, called the Robb Reservoir parcel “a natural jewel,” adding that it offered still water for paddling as well as connections to other conservation lands. The property lies within the Harris Center’s so-called SuperSanctuary, a conservation area featuring more than 36,000 acres.

Eric Masterson, the Harris Center’s land program manager, says motorboats would have upended more than just the peace and quiet. “We have a milfoil problem in this region,” he said, referring to the aquatic invasive plant, “and motorized craft would only exacerbate this.” In this case, maintaining solace on the water is a benefit to more than just humans; it’s helping preserve the integrity of the ecosystem itself.

Lisa W. Foderaro is a senior writer and researcher for Trust for Public Land. Previously, she was a reporter for the New York Times, where she covered parks and the environment.

The Active Transportation Infrastructure Investment Program (ATTIIP) is a vital initiative that helps expand trails connecting people to nature and their broader neighborhoods. Despite this importance, Congress allocated $0 for ATTIIP in this year’s appropriations process. We cannot delay investments in safe, active transportation systems. Urge Congress to fully fund the ATTIIP!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.