Q&A: Urban Designer and Author Alison Sant

Q&A: Urban Designer and Author Alison Sant

This Earth Month, we spoke with author Alison Sant, whose new book, From the Ground Up: Local Efforts to Create Resilient Cities, examines how community-driven approaches to urban planning can help solve multiple priority problems in tandem, from combatting the impacts of climate change to righting racial and environmental injustices.

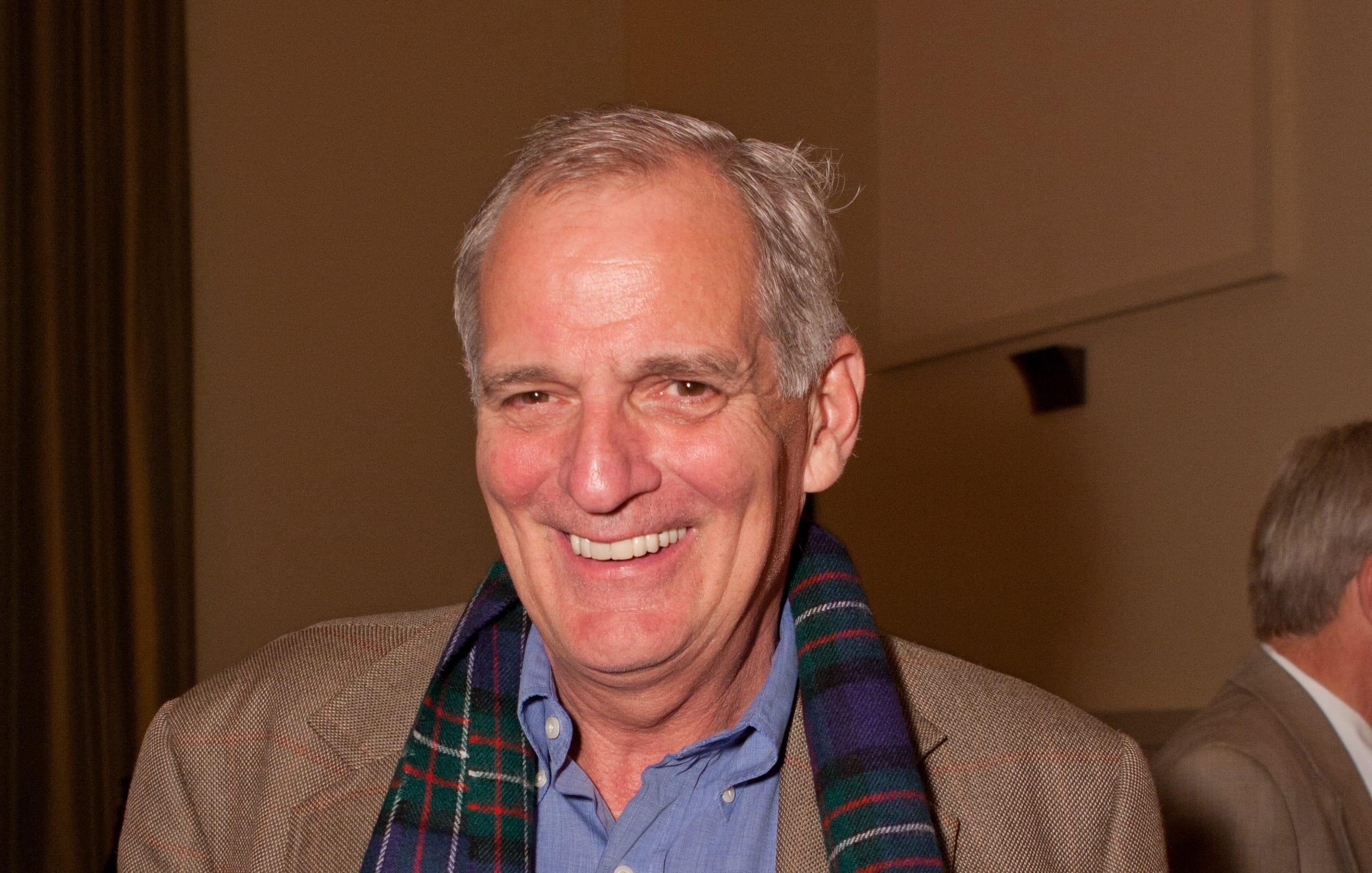

Alison SantPhoto credit: Island Press

Alison SantPhoto credit: Island Press

How did you come to the idea of writing this book?

I came to this as a designer. I’m the cofounder and partner in the Studio for Urban Projects. We’ve worked primarily in the Bay Area on a lot of projects that are focused on urban prototyping—ways of rethinking everything from our city streets to our shorelines. Using the methods of tactical urbanism, we’ve been trying to suggest solutions for climate change, and we’re working closely with communities in the Bay Area. We know that we have less than eight years to avoid the worst of climate change’s effects. What’s been inspiring to me is finding a lot of people who are doing very helpful work in communities all across the country that is like the work we were doing in San Francisco. This book was a chance for me to dive into that and find solutions that I find extremely helpful and lay the seeds of how we can move forward.

In the book, you posit that cities must remake themselves in pieces. Given the scope of the work but also the urgency, layered with the realities of budgets and person-power, how can communities prioritize tactics to make the broad and quick progress we need?

That idea that cities are made in pieces really came out of watching how cities progress over time by remaking things constantly. We know that climate change exaggerates existing systemic inequities because communities are exposed disproportionately to its effects. And climate change is entangled with so many other social crises. In working to address climate change, we also need to address social justice. In From the Ground Up, I focused on communities that need those changes urgently. Creative, effective solutions—whether in small communities or in large—need to be seeded locally and then grow from there. And there are some great examples in the book of how that’s done. In New Orleans, post–Hurricane Katrina, there was a woman named Angela Chalk, who is the executive director of healthy community services in the Seventh Ward, one of the neighborhoods that was hit the hardest by Hurricane Katrina.

Unfortunately, the history of systemic racism has condensed much of New Orleans’ Black population in the lower-lying areas of the city. When the storm hit, it had disastrous effects for many of those communities. Chalk was one of the first people to move back to her neighborhood. And working with Water Wise Gulf South, which is a local advocacy group, she was able to direct investments to her neighborhood. And she started by just creating bioswales and green infrastructure demonstrations in her own backyard. A group of volunteers got together, and they put in a bioswale, and they added rain barrels and other green infrastructure amenities around her house. And when the next storm hit and she didn’t flood, her neighbors wanted the same remedies in their yards too.

Angela was able to bring people together to learn how green infrastructure works and how it complements the complex system of levies and pumps and canals that run through New Orleans. So now the Seventh Ward has entire neighborhood blocks of demonstration projects. And they’re part of a local group called the Water Wise [Neighborhood] Champions. And really people in the Seventh Ward and other wards are learning how to connect their own local knowledge of what happens in times of flooding with technical information about how green infrastructure works. So as Angela said in our interview, everybody’s a green infrastructure specialist now in her neighborhood.

If these efforts were imposed upon communities, they likely would’ve been met with some resistance. And I found in researching the book that was true, whether you’re talking about green infrastructure or you’re talking about bike lanes, or you’re talking about parks. In New Orleans, these community-led approaches are being really expanded upon as entire resilience districts are now underway.

In the book, you share stories of how cities are adapting to how a changing climate is affecting the existing infrastructure and stories of communities that aim to reverse some of the effects. Which stories stand out?

Often the best or the most interesting projects are really doing both, right? Whether we’re talking about adapting to climate change or mitigating its impacts, climate action is really an opportunity to create more equitable and livable cities.

Trust for Public Land has a project in Philadelphia that was incredible. Philadelphia is the poorest big city in the country, and, like many Americans, only one in three Philadelphians have access to a park or a green space within walking distance. So this puts a fine point on the way in which the history of racism and redlining and restrictive covenants have made the realities of adapting to climate change different and mitigating climate change different in different neighborhoods.

Many of the parks in Philadelphia are really parks in name only. They’re on the map, they’re indicated, but they’re not really facilities that offer critical open space, and they’re not mitigating flooding or cooling neighborhoods currently or providing social resilience to the surrounding neighborhoods. When Philadelphia was trying to meet its own stormwater goals and its EPA consent decree in order to do that, they launched a really ambitious plan to make a third of the city’s impenetrable landscapes penetrable and to manage stormwater—and in that process really use parks and open spaces as the way to do that.

Trust for Public Land’s work started with just 10 pilot projects and then quickly scaled to 25. In Philadelphia, [the schoolyards program] was used to create green infrastructure, to create classrooms where kids could learn from the plants and animals in their own backyard where they were provided with healthy places for outdoor play, and all the while this is capturing stormwater and cooling neighborhoods and doing all the things we need to do around climate change. But even in the day to day, it’s also really making the lives of students so much better.

Green schoolyards were only one piece of the work in Philadelphia. Parks were also a really important piece. I got the chance to tour Lanier Park, which is in Grays Ferry in South Philadelphia, which was one of these parks by name only. It had been closed and gated for a decade. Residents had been divided by generations of significant racial conflict. And TPL in its hallmark community design process, which has been used in so many cities and many of which are covered in the book, really brought people together in neighborhoods surrounding the park holding meetings in different parts of the neighborhood, making sure that people showed up and could sit together so that people weren’t just sitting with their own neighbors and people they knew; they were sitting with people they didn’t know.

And then through a directed process, people were able to participate in what they wanted this park to become. After years of abandonment, the park is thriving, and people come together now around playgrounds and dog parks and picnic tables. There was a friends-of group that had a walking club, and the park manages water for the entire neighborhood in the process. Lanier Park and the process that redesigned it provides a venue for creating social infrastructure that makes these neighborhoods resilient…and the work to repair this neighborhood is not complete. It’s still very much underway, but with a common public park to steward, there’s a substantial incentive for neighbors to keep coming back to the table, to keep getting to know one another and to keep making their neighborhood park what they hope it will be.

A lot of the stories that you tell in the book focus on parks or what we think of as these defined, contained spaces and the value that they bring. But you open the book with several chapters about reclaiming the streets either for more park space or for more active transport corridors, which can address climate, public health, and systemic racial inequity.

Transportation is a big focus of the book. It’s responsible for 29 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., and much of that is due to passenger cars. I focus on how we reclaim our streets to make safe spaces for walking, biking, and public transit…how can we use our roadways for people instead of just cars.

Minneapolis is covered with incredible greenway infrastructure. People travel by bike from the suburbs and into the city using this really robust network of trails. And it’s a wonderful way to get around the city even in the winter. But that network has not been equally distributed. And in north Minneapolis, there’s a group called the Northside Greenway Now that is trying to make sure that greenways can be part of the fabric of north Minneapolis in addition to other parts of the city.

I found that was also true of other neighborhoods in other cities in the book. One example is Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York. New York is one of the best cities in the country for public transit. Over 60 percent of people in New York don’t own cars, but there are still transit deserts like Bed-Stuy; there are still people who have extremely long commutes; there are still people who can’t pay the fare to use public transit. Bed-Stuy Restoration, a community development corporation, led an initiative to create the New York City Better Bike Share Partnership to create access to transit through bike share but also to create more healthful ways for people to get around. It was a health initiative as much as it was a transit initiative.

Bike share had launched in Bed-Stuy, but it wasn’t being used by residents. Part of that was its association with gentrification and displacement. It wasn’t a program that was initiated by residents there. It was initiated by Citi Bike, and people felt like it wasn’t necessarily for them. It was pricey; it wasn’t necessarily something to people were used to using it or knew how to use. So the New York City Better Bike Share Partnership launched a campaign to create access to the bike share system. They brought people together with community events where they hosted helmet giveaways and bike safety lessons and neighborhood rides. Youth from the neighborhood were hired as local ambassadors to survey residents and find out what they needed and wanted, what would make the bike share system more useful to them.

Bed-Stuy Restoration [Corporation] met with local precincts to talk to police about racial profiling and make it safer for people of color to use the system, which is just as significant in areas like Bed-Stuy or north Minneapolis as it is in having safe trails or bikeways. Resolving racial profiling is a huge part of making bike share systems and biking accessible. There were 170,000 more Citi Bike trips in Bed-Stuy in the year the program launched and membership increased 56 percent, which is more than it did citywide.

Something else that you touched on just now and many times in the book is the risk of gentrification and unintentional displacement. How do we ensure that infrastructure improvements don’t have those unintentional but negative consequences?

Green gentrification came up a lot in my interviews. Whether you’re talking about parks or bikeways or other kinds of infrastructure that bring investments to neighborhoods, many of the people that I talked with in the book made the distinction between wanting investments in their neighborhoods to reverse generations of discrimination but not wanting displacement. It’s critical that communities are centered in the development of plans so that these projects can economically benefit those communities as well. This speaks to a main theme in the book, which is that the most effective solutions are born out of the communities they serve.

The India Basin Shoreline Park in San Francisco is in the southern part of the city, in a neighborhood called Bayview–Hunters Point. The ambition for the program is to create a 64-acre network of parklands and open spaces that run along that shoreline. Historically, the Bayview has had some of the highest rates of home ownership among Black people in the city, but it’s also suffered from generations of environmental injustice and profound neglect for basic infrastructure.

The park design has many incredible features that bring people to the water. It’s part of a larger vision about using nature-based adaptation solutions Bay-wide. It will have oyster reefs; it’ll have wetlands, and there’ll be kayaking and beaches there. They are all part of addressing shoreline adaptation of a relatively low-lying part of the city.

A group was assembled to bring long-term residents that have historically been underrepresented into the planning process. The committee has created the [India Basin] Equitable Development Plan, which addresses how the park’s development will catalyze economic opportunities for residents, promote workforce development, create housing security, and support community health all while creating the natural ecology of the shoreline in the process of inventing the park. If this model’s successful, the Equitable Development Plan can inform ways in which parks can improve the lives of residents while providing generous public spaces and improving neighborhoods in places that really need those investments the most.

We’re talking to you today and this month because it’s Earth Month, so climate and climate resilience is top-of-mind. And next month we will be releasing our 11th annual ParkScore® report. This year’s theme is climate, and we’ll reveal unique data and new stories on how cities are using parks to become more resilient to extreme heat, flooding, and other impacts of the climate crisis. The report will have case studies similar to the ones in your book. For cities and towns, especially smaller towns, rural towns, or even smaller urban cities that don’t have the ability to create ambitious master plans or projects, how can policymakers and citizens make these types of investments and strategies a priority and make them attainable?

Sometimes cities don’t have the funding or political leadership of a city like New York, which has been enormously ambitious. Often in the absence of that political leadership, there’s a very strong local network of advocacy groups and even other government institutions that may have worked together with those groups in the past. One fantastic example in the book is in Baltimore, where the U.S. Forest Service has actually played a really formative role in the city, working with nonprofits like Humanum as well as city government. But in Baltimore, like many cities across the United States, systemic racism has informed its landscape. Baltimore’s affluent neighborhoods may have as much as 50 percent tree canopy cover, but in east Baltimore, which was a community that was redlined, there can be as little as 6 percent. So that means that on a hot day, there can be as much as a 16-degree temperature difference just between two neighborhoods across the city.

In addition to that, redlining has created a history of underinvestment in neighborhoods. There are more than 30,000 properties in Baltimore that have vacant buildings or lots. One of the projects—again, getting back to this idea that really holistic solutions are our most effective way of addressing the climate crisis and addressing social injustice—the Baltimore Wood Project is an excellent example of that. It employs people with barriers to employment—many of them have been formerly incarcerated—in the process of salvaging wood from the city’s 4,000 abandoned buildings. To provide some context, in the United States, there’s more wood material going into landfills than is harvested from on the national forest. So as this wood decays in landfills, it releases carbon that would otherwise be stored. So the U.S. Forest Service is really interested in finding solutions to this as a way of addressing climate goals…but also looking at how this could lead to more equitable solutions and ones that create economic benefits for the people in Baltimore.

So people are hired to deconstruct these buildings and then the wood is sold to companies like Room & Board, which has created a line of bookcases and tables that are named after the streets in Baltimore where they came from. And the lots where the houses that are deconstructed once stood are now being converted into small parks and urban forests that can sequester carbon and clean the air and cool the neighborhoods and also contribute to the city’s 40-percent tree canopy goal. Baltimore deserves more resources to meet these ambitious goals. But even without them, they’re providing an extraordinary example of how social justice and climate action can be integrated.

Alison Sant is a cofounder and partner of the Studio for Urban Projects, an interdisciplinary design collaborative based in San Francisco. She has taught at the California College of the Arts; the San Francisco Art Institute; and the College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley.

In honor of Earth Month, Island Press is extending the TPL audience an offer of 20 percent off From the Ground Up: Local Efforts to Create Resilient Cities. Visit https://islandpress.org/books/ground and enter the code “ground” for the discount.

Rising temperatures, bigger storms, and asphalt schoolyards pose significant risks during recess. Urge Congress to prioritize schoolyards that cool neighborhoods, manage stormwater, and provide opportunities for kids to connect with nature today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.