Civil Rights Leader Ben Jealous on Lifting up Black History and Culture

Civil Rights Leader Ben Jealous on Lifting up Black History and Culture

Before Ben Jealous emerged as a civil rights leader on the national stage, taking the helm of the NAACP from 2008–2013, he was a kid splitting time between worlds.

Jealous, who joined The Trust for Public Land’s board of directors in February, spent his school years with his parents in Pacific Grove, California, and his summers with his grandparents in West Baltimore, Maryland. During the school year he nurtured a dream of becoming an oceanographer, becoming the youngest-ever tour guide at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Summers, he hung out back East with his mom’s family. His family’s church sits on Lafayette Square Park in Baltimore, a place that he calls “a center of the free Black community before the end of slavery.” His mother was among a handful of Black students who integrated Baltimore’s Western High School in 1955.

Trust for Public Land board member Ben Jealous

Trust for Public Land board member Ben Jealous

Jealous says it’s that mix of love for nature, history, and dedication to social justice that brought him into The Trust for Public Land community. Today he sits on our Black History and Culture Advisory Council, a group of experts in the movement to lift up a more accurate and equitable history of the nation. Jealous and his colleagues on the council are supporting upcoming projects like protecting the Connecticut farm where Martin Luther King Jr. worked as a teenager and the spot in Natchez, Mississippi, that was once among the nation’s largest markets for the sale of enslaved Africans.

[Help us catalyze the movement to preserve Black history and culture: Give today.]

We caught up with Jealous to learn about how his family history and his commitment to civil rights shapes his approach to environmental justice and how he connects with the natural world.

How’d you get interested in history?

Part of it was growing up in a family that knows its history. My mom’s family has lived within 50 miles of Chesapeake Bay in Maryland and Virginia for the better part of 400 years. We know this because we descend from the earliest white settlers in the area and their African slaves. My father’s family comes from New England, and we know of seven members who fought in the Continental Army, including the youngest combatant at the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

It was my town’s ghost stories that allowed me to understand that even in very small places, the cultural history can be rich and full of contradictions and complexities. The people who’d curated our town’s ghost stories went off script from the otherwise very white telling of our town’s history. Through ghost stories we learned about Chinese railroad workers, Japanese fishermen, Native Americans, Buffalo Soldiers, white Methodist idealists and old conquistadors, in addition to white settlers. The ghost stories revealed both the region’s rich cultural heritage and its long history of racial violence.

[Read more: Saving the Connecticut site of a little-known chapter in Martin Luther King Jr.’s life story]

How have you put that early interest in history to work in your life and career?

As a student, I was suspended from Columbia University for a series of protests against the demolition of the Audubon Ballroom. This was an epicenter of Black, Jewish, and Puerto Rican life in Harlem, and it was also the place where Malcolm X was assassinated. They ended up tearing most of it down to build a biogenetics facility, but they did save a small portion of the original building. Meanwhile, Harlem is both the second-oldest and the largest neighborhood in Manhattan. It makes up approximately 30 percent of the island’s land mass. But at the time I was protesting against the demolition, it had only 5 percent of Manhattan’s recognized historic landmarks. I continue to be haunted by how disposable our Black cultural sites are.

Jealous was suspended from Columbia University for protesting the planned demolition of the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. A statue of Neptune is part of the building’s original facade, which remains standing after much of the structure was demolished. Photo credit: By Beyond My Ken – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Jealous was suspended from Columbia University for protesting the planned demolition of the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. A statue of Neptune is part of the building’s original facade, which remains standing after much of the structure was demolished. Photo credit: By Beyond My Ken – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

What do we lose when we ignore the full history of a place?

I’m advocating for historic preservation and restoration at a place called Beechwood Park outside of Annapolis: in the 1940s, it was the first integrated vacation community in Maryland. It had two bandstands where many of great Black musicians of the 1940s, 50s, and 60s performed. The rest of the area was closed off to people of color by white-only covenants, so that place was a refuge for working class urban families, a way for their kids to spend time in nature. My grandparents rented a cottage there and brought my mom there when she was a child.

What happened to the land after that?

The land taken for unpaid taxes in early 1970s, and eventually the county took possession of it. Now all that’s there is a trail through a forest to the riverbank and a couple of decrepit bandstands. Most people like me who are dragging their kayak off the Subaru and carrying it to the water’s edge have no understanding of the history they’re tiptoeing past. They don’t know that jazz, R&B, and rock and roll legends played there—they have no idea how sacred the ground they’re walking on is.

[Read Six insights: Preserving Black history for a more equitable future]

How are you planning to celebrate Juneteenth this year?

Juneteenth is a time to talk to my kids about the role slavery played in our family’s history and the nation’s history. My grandma turns 105 in November. She knew her grandparents like we know her, and her grandparents were born enslaved. Juneteenth is a time to make sure the next generation hears her stories and understands how much we’ve overcome—and how much remains to be done.

The movement to catch up with history and tear down Confederate monuments has created a question of what to replace these monuments with. To me, it seems so obvious: there’s so much rich history of Black America, and so far, our Black heroes and their contributions have been so undervalued. Conservation has historically been a very white-led field. For instance, whenever we visit Yosemite National Park, I tell my kids about the Buffalo Soldiers, the Black members of the U.S. Cavalry who were the park’s first rangers in the late 1800s. Yosemite is such a recognized place, but the contributions of Black people in the park are erased, so most visitors never hear that story.

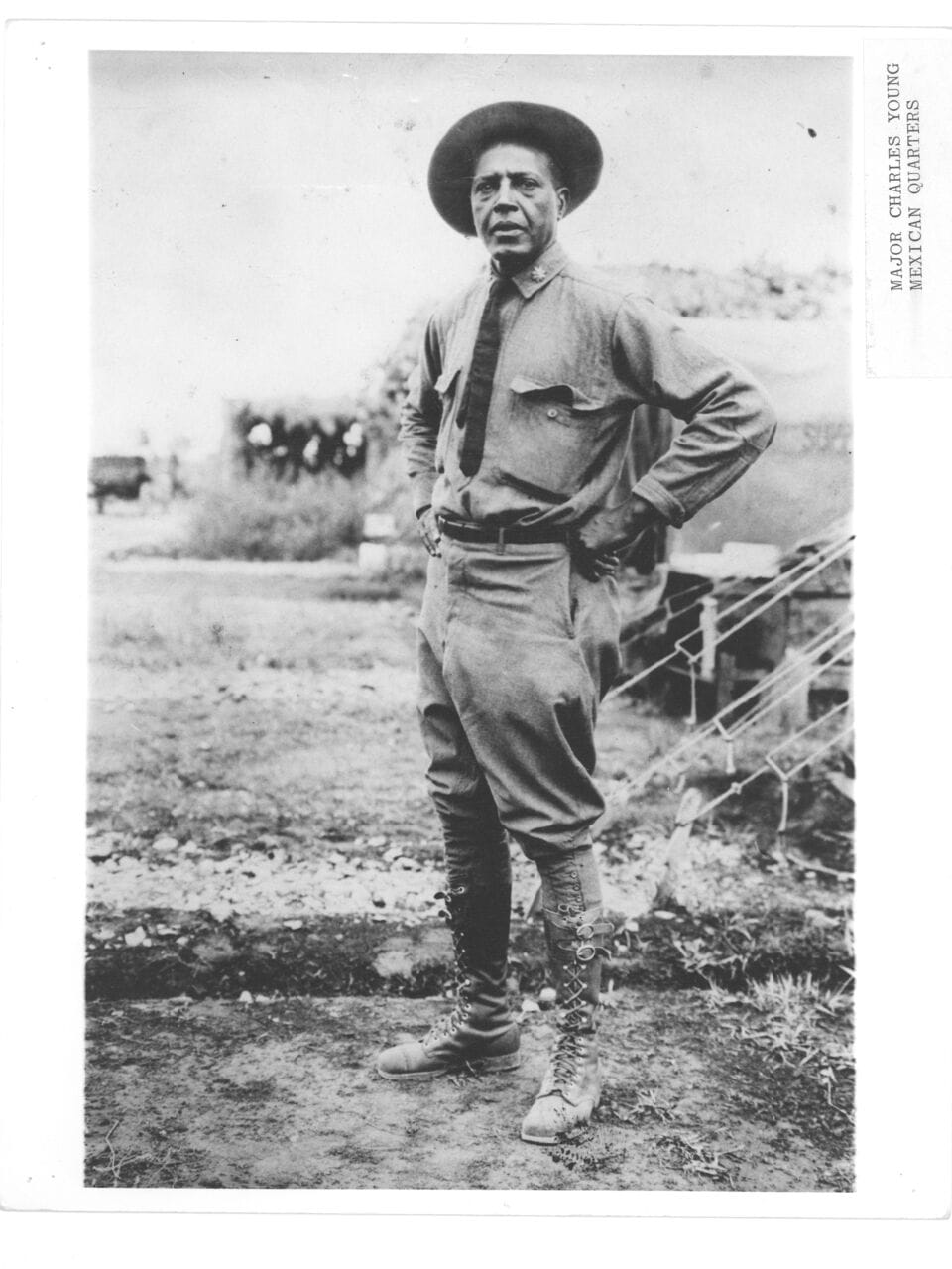

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Young distinguished himself throughout his military career with the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th Cavalries. We helped preserve his home as part of the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument. Photo Credit: The Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Young distinguished himself throughout his military career with the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th Cavalries. We helped preserve his home as part of the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument. Photo Credit: The Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City

What’s the value of preserving and uplifting an accurate and diverse history of the nation?

One of the concepts that sticks with me from my training as a tour guide at Monterey Bay Aquarium when I was twelve years old is the importance of upwelling to the health of our oceans. That’s a natural process where cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean rises to the surface and infuses the ecosystem with food and energy.

It’s so easy for ghosts, wisdom, traditions, and all the vibrancy of a community to get trapped in unused land. But if we can bring to that place an intentionality and understanding of what communities need today, and an awareness of what that place has meant in the past, then you have a cultural upwelling. The churning in that space where the past meets today’s needs allows people and communities to thrive.

Right now, you have the opportunity to double your gift and your impact to advance the most critical projects and build capacity to celebrate and honor the story of Black America. An anonymous donor has stepped forward with $250,000 in matching funds to match your gift dollar-for-dollar. Give today.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.