The Health Superpowers of Parks

Green spaces are increasingly valuable, cost-effective public health resources that can drive mental, physical, and environmental outcomes for communities.

Executive Summary

- Parks promote health by serving as an ideal venue for physical activity, helping to reduce obesity and the risk of numerous diseases . Parks with

active amenities and staffed programming, such as walking loops or fitness classes, are associated with significant increases in physical activity. - Spending time in natural areas, whether walking or reflecting in a garden, is a powerful strategy for improved physical and mental health . There is a vast body of evidence documenting the health benefits, ranging from reduced anxiety and depression to improved birth outcomes.

- Parks provide a platform to bolster social connections through both structured group activities and informal encounters. Social connections improve health, as people who are lonely are more likely to get sick and die younger.

- Parks improve urban environments and help protect residents from the growing threat of climate disasters—heat waves, severe flooding—and other urban health threats such as air, noise, or light pollution.

- Park equity is health equity. Access to parks and green spaces offers especially strong health benefits for people with low incomes—those most likely to be in poor health.

Findings: Across the Country, Parks Departments and Their Partners Are Leveraging Parks to Improve Health

- According to our annual survey of park systems across the 100 most populous U.S. cities, we find that park systems are stepping up to deliver for health in new and surprising ways . When asked to share their most effective strategies at improving physical or mental health, most parks and recreation agencies named a camp, sports league, or fitness class . That isn’t surprising . What is surprising is that a greater number of agencies also named something else, whether that’s partnering with a program like Generation Wild in Colorado, which introduces young people to the outdoors through weekend outings, or funding unassuming “NeighborSpaces” like El Paseo Community Garden in Chicago, which provided a lifeline to seniors during the pandemic.

- We also find that healthcare institutions—hospitals, public health agencies, and even insurance companies—are beginning to see their roles a bit differently . In 26 of the cities surveyed, a healthcare institution is funding, staffing, or referring patients to health programs in parks as part of efforts to improve patient and community health.

- We know parks are good for our health, but they deliver health benefits only when people visit and use them. From our research, we identified 14 ways in which cities can increase park usage . These actions should be adopted as health promotion strategies by health institutions . They fall into one of three key categories:

- Ensure everybody has access to parks and natural areas where they feel welcome.

- Make parks as health-promoting as possible.

- Bring on the partnerships! Deploy the resources, expertise, and energy of the health sector to activate parks as a health promotion strategy.

Residents painting a mural at El Paseo Community Garden in Chicago. The garden is protected by a nonprofit called NeighborSpace, with funding from the city. Photo: El Paseo Community Garden

Evidence: Parks Are Really Good for Mental, Physical, and Environmental Health

Many of us have experienced the pleasures of taking a walk in nature or simply sitting beneath a tree on a beautiful day. Leaves and grass, birdsong and breezes, the smell of soil as it stirs to life in spring—all leave us feeling refreshed and energized. But what has come into focus in recent years are the many tangible health benefits, both physical and mental, that spending time in nature can yield.

Many of us have experienced the pleasures of taking a walk in nature or simply sitting beneath a tree on a beautiful day. Leaves and grass, birdsong and breezes, the smell of soil as it stirs to life in spring—all leave us feeling refreshed and energized. But what has come into focus in recent years are the many tangible health benefits, both physical and mental, that spending time in nature can yield.

Hundreds of studies across the globe have examined exactly what happens to hormone levels, heart rate, mood, ability to concentrate, and other physiological and psychological measures when we are immersed, even briefly, in the natural world. Other studies have looked at long-term outcomes: body weight, cardiovascular disease risk, life expectancy. The extensive evidence converges on the same conclusion: being outdoors, especially outside in green spaces, is good for our health.

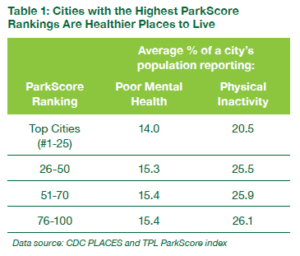

For over a decade, Trust for Public Land has published the annual ParkScore index, a ranking of the park systems in the 100 most populous U.S. cities. One of the motivations for publishing this index is to raise awareness of the superpowers of parks to address some of the most complex problems facing cities today, including health challenges such as rising obesity rates, mental health problems, and loneliness. From this analysis, we know that cities with the highest ParkScore rankings are healthier places to live. In the top 25 ParkScore cities, people are on average 9 percent less likely to suffer from poor mental health, and 21 percent less likely to be physically inactive than those in lower- ranked cities (Table 1). These patterns hold even after controlling for race/ethnicity, income, age, and population density.

Dr. Howard Frumkin, a senior vice president at Trust for Public Land and coeditor of Making Healthy Places, says that parks and green spaces have “public health superpowers,” adding that park administrators and health professionals should think of parks as part of a holistic public health strategy.

“If we had a medicine that delivered as many benefits as parks, we would all be taking it,” says Frumkin, the former dean of the University of Washington School of Public Health and a past official of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Parks deliver cardiovascular benefits, fight loneliness, combat osteoporosis, counter stress and anxiety, and more. And they do those things without adverse side effects and at minimal cost.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, that was especially true. The virus is much less likely to spread outdoors, and with health clubs, restaurants, and movie theaters shuttered, many people sought physical activity and social connection in parks and on trails. Green spaces are also a balm for the distress, loneliness, and grief associated with modern stressors ranging from social media to divisive politics to the opioid epidemic.

Only a quarter of American adults are meeting the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidance for physical activity: getting 150 minutes of moderate exercise and two days of muscle strengthening per week. Increased physical activity is associated with numerous health benefits, such as reduced obesity, reduced osteoporosis, lower blood pressure, enhanced child development, and improved mental health.

Parks and green spaces provide an ideal venue for physical activity. So perhaps it’s no surprise that close-to-home parks are associated with lower obesity rates and improved health in both young people and adults. More and more park agencies are capitalizing on that connection, leveraging green spaces to boost physical activity. Park managers are installing walking loops, courts for a variety of sports, skate parks, climbing boulders, and fitness zones with equipment that replicates that found in health clubs.

A 2016 national study of neighborhood parks found that the presence of such amenities was associated with a rise in physical activity. Staffed programming, such as fitness classes, dramatically increased physical activity; each additional supervised activity increased park use by 48 percent and moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) time by 37 percent. More and more, residents around the nation can attend fitness, yoga, meditation— and even kickboxing—classes in parks and local recreation centers.

“I think the COVID pandemic shone a light on the fact that regular movement and being outdoors is really important for physical and mental health and well-being,” says Dr. Amy Bantham, president of the Physical Activity Alliance, the nation’s leading coalition dedicated to promoting physical activity for health. “The questions now are: How can we make the opportunity to do so easy, safe, and accessible for everyone? How can we provide people the infrastructure and programming they need to be active outdoors?”

Studies show that easy access to parks is associated with increased physical activity and lower body mass index. Photo: Adair Rutledge

Photography

Overweight and obesity are alarmingly common in the U.S., and a 2014 study in the journal Preventive Medicine underscored that parks are part of the solution. The study, which relied on five years of survey data, looked at individuals’ body mass index (BMI) and characteristics of nearby parks—both size and cleanliness—in New York City. The researchers found that “greater neighborhood park access and greater park cleanliness were associated with lower BMI among adults.” (The study adjusted for other neighborhood characteristics such as homicides and walkability, which could influence park usage.)

Still another study, in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, examined children ages 6 to 12 in Valencia, Spain. It found that park and playground access was “significantly associated” with increased physical activity, especially on weekdays, and contributed to lower BMIs overall. Parks promote health by serving as a setting for physical activity, helping to reduce overweight and obesity, and reducing the risk of numerous diseases.

Contact with nature is a powerful strategy for better health. While we don’t yet fully understand all the ways in which nature benefits health, they likely include stress reduction, attention restoration, improved immune function, and perhaps even inhaling biogenic compounds released by trees, to name a few mechanisms. But a vast body of evidence, in studies of both adults and children, confirms the astonishing range of mental and physical health benefits contact with nature provides. They include lower blood pressure, improved birth outcomes, reduced cardiovascular risk, less anxiety and depression, better mental concentration, healthier child development, enhanced sleep quality, and more.

Exposure to and interaction with nature in parks can take many forms—from strolling to community gardening, from “green exercise” to quiet, meditative “forest bathing.” Each of these experiences benefits health. This became especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, a 2022 study in the journal Health & Place examined the incidence of depression and anxiety among older people during the pandemic. It found that those with access to neighborhood parks were much less likely to report symptoms of depression or to screen positive for anxiety than those without.

Results were strongest for respondents who enjoyed access to six to 10 parks in their communities. A 2023 study conducted in Philadelphia and published in the journal PLOS ONE found that those who lived closest to green space reported better physical health and less stress than those who lived farther. But proximity didn’t tell the full story; actually visiting green spaces during the pandemic was linked to better mental and physical health and less loneliness. Contact with nature—one of the major attractions of parks and green spaces—is clearly a path to better health.

Far too many Americans suffer from loneliness. Nearly half of Americans report feeling alone or left out sometimes or always and lacking meaningful social interactions on a daily basis. One in five reports rarely or never feeling close to other people. Loneliness, consequently, undermines health. People who are lonely suffer worse immune function and are more likely to develop infections such as COVID-19. Their mental health suffers, their risk of heart attacks and stroke rises, and they die younger. Loneliness is toxic.

Parks and green spaces are part of the solution. Park access can bolster social connections. Structured group activities such as community gardening and tree planting bring people together, but even informal encounters while minding children in a playground or walking on paths can yield gratifying social contacts. People commonly have social gatherings in parks, and children make new friends there. Parks have even been shown to foster bridge-building between different racial and ethnic groups.

“There is a lot of evidence that the presence of green space in neighborhoods fosters community cohesion, allowing for people to know their neighbors, and promotes safety,” says Dr. Georges C. Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “We know that play is absolutely essential for childhood development. To the extent park agencies can put things in that allow for people to engage with one another, whether running paths or bicycle paths or play equipment—all of those things are very, very important to promote human health.”

A 2013 study in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning surveyed residents in three urban neighborhoods in Manchester, England. It found that parks provided an “important cultural ecosystem” for those communities. “As recreational spaces,” the study noted, parks “attract visitors, provide opportunities for social interactions and, thus, contribute to the development of new social ties and strengthen existing contacts.”

Young children playing in South Oak Cliff Renaissance Park in Dallas, Texas. Trust for Public Land is working with cities nationwide to put a park within a 10-minute walk of every resident. Photo: Jason Flowers

Unfortunately, not everyone has equal access to quality parks. Park inequities, in turn, contribute to health inequities.

Dr. Pooja S. Tandon, a pediatrician and researcher at Seattle Children’s Hospital, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, and a fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics, says easy access to parks is key. She urges all cities to make sure every neighborhood has ample green space. “Although there is evidence of all kinds of nature contact being important, whether state parks or deep wilderness, having access to parks near children’s homes is really critical,” she says. “We know that it is not equitable, however.”

Indeed, Trust for Public Land has found serious disparities in access to the outdoors. In an analysis of the 100 most populous American cities, neighborhoods where most residents identified as Black, Hispanic and Latinx, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Asian American and Pacific Islander had access to an average of 43 percent less park acreage than predominantly white neighborhoods. Similar park-space inequities existed in low-income neighborhoods across cities. A growing body of research in recent years has confirmed this pattern.

Tandon and other health experts agree that putting parks within a 10-minute walk (or roughly a half mile) of people’s homes is a worthy and achievable goal. Such close-to-home access is one of five measurements used to assess city park systems in TPL’s annual ParkScore index.

“The 10-minute walk to a park metric is a good way to look at the access we know children need for their health and well-being,” Tandon adds. “Accessing faraway nature is wonderful, but it’s not easily accessible to everyone, especially children. When you think about the cadence of families’ lives and the importance of daily contact with nature, having access to parks near homes and schools is vital.”

Trust for Public Land is working with communities and municipalities around the country to help accelerate access to close-to-home parks. Bianca Shulaker Clarke, TPL’s Parks initiative lead and senior director of the 10-Minute Walk® program, says more than 300 major cities have already signed on to Trust for Public Land’s 10-Minute Walk commitment, in which mayors pledge to improve park equity.

“Parks can help city leaders achieve their priorities, especially when green spaces exist within a 10-minute walk of every resident,” Shulaker Clarke says. “Such proximity sets the stage for long-term health, vitality, and resilience. Centering residents in this work—from policy implementation to programming choices—ensures that parks are well used, while maximizing health benefits and strengthening communities.”

Park equity is not only the right thing to do; it’s a sound public health strategy. That’s because access to parks and green spaces offers especially strong health benefits for people with low incomes—those most likely to be in poor health. This is called the “equigenic” effect, because it reduces health disparities, increasing health equity between the wealthy and the poor and across racial groups. The equigenic effect of nature contact was first described in a 2008 paper in The Lancet, with regard to all-cause mortality and heart disease. Since then, it has been shown to apply to mental health, COVID risk, birth outcomes, and many other health conditions. Parks and green spaces are a path to health equity.

However, park projects can lead to unintended outcomes and even worsen inequities. When neighborhood conditions improve—a process called gentrification— long-term residents may feel a sense of social alienation and exclusion depending on how the changes happened. Just because a park is public does not mean that everyone will feel welcome there. In addition, real estate prices can rise, displacing longtime residents—a serious threat to their health and well-being.

Recent studies suggest that new parks and park upgrades do not invariably lead to gentrification. A study by Alessandro Rigolon and Jeremy Németh reviewed the gentrification impact of 621 new parks and greenways across 10 U.S. cities between 2000 and 2015 (with gentrification defined as a steeper increase in a neighborhood’s income, education, or housing value than that of the city median). In general, new parks were not associated with gentrification. However, greenway parks with walking and cycling trails—think iconic projects such as New York’s High Line, The 606 in Chicago, or Atlanta’s BeltLine—were associated with nearby gentrification. So were parks close to downtown areas.

Access to parks and green spaces offers particularly impressive health benefits for people with lower incomes, who are also most likely to have health challenges. Photo: Chris Bennett

Gentrification—the improvement of neighborhood facilities, accompanied by rising incomes or property values—is not inherently a bad outcome. It’s the exclusion and displacement of neighborhood residents that raise equity concerns. Many researchers and advocates have identified strategies for preventing displacement. These include preserving existing affordable housing; helping long-term residents remain through policies such as rent control, incentivizing (or requiring) developers to construct affordable housing, supporting community-based organizations that create and manage affordable housing, and tax-increment financing to support affordable housing.

Empowering community organizations; deeply engaging these organizations in design and operation of parks and public spaces; and promoting vocational training, local hiring, and small business development all play a role in avoiding displacement and strengthening existing communities.

“There is no one magic bullet, but the strongest strategies to prevent displacement are through empowering communities and tying park creation to other efforts such as affordable housing and small business development,” says Frumkin. “We have good evidence that these holistic approaches help blunt the displacement that can result from gentrification. Being able to stay in your neighborhood as parks and green spaces improve is good for your health.”

Just as an abundance of quality neighborhood parks can lead to positive health outcomes, a lack of such parks can threaten health. Heat waves in the U.S. have tripled compared to the long-term average. This trend is expected to intensify, with nearly one in three Americans expected to live in a city experiencing more than 30 severe heat days per year (heat index above 105 degrees) by 2065, a dramatic increase from less than 1 percent of the population experiencing this today.

Extreme heat can lead to heat exhaustion, heatstroke, poor mental health, and cardiovascular stress. Excessive heat has even been shown to reduce students’ test-taking abilities.

The evidence to date suggests parks are one of the most effective ways for cities to protect their residents from the effects of extreme heat. Pavement and other dark surfaces absorb and reradiate heat far more than grass, plants, and trees—contributing to the urban heat island effect, which creates exceedingly hot neighborhoods where parks and vegetation are scarce. Recent analyses of historically redlined neighborhoods around the country have found that those areas suffer from higher rates of extreme heat than areas that were not subject to the discriminatory practice. (In the 1930s, banks drew red lines around majority Black neighborhoods they deemed too risky for home mortgages.)

A woman enjoying the view in Greenfield, New Hampshire, where Trust for Public Land partnered with a foundation to create a 3-mile accessible trail that winds through woods and wetlands. Photo: Al Karevy Photography

But parks and trees temper that. Trust for Public Land assembled the highest-resolution heat data available for the United States, revealing a stark difference in temperature between neighborhoods that have parks nearby and those that do not. Specifically, our researchers analyzed thermal satellite imagery for 14,000 cities and towns and found that areas within a 10-minute walk of a park can be as much as 6 degrees cooler than neighborhoods outside that range.

Areas lacking green space are also more prone to flooding since soils and vegetation can capture stormwater before it inundates streets and homes. And floods are on the rise. Researchers from Stanford University recently concluded that rainfall fueled by climate change was responsible for almost $75 billion in flood damage in the United States since 1988. This is an equity issue, as communities of color are disproportionately affected by severe flooding.

Flooding harms health in two ways, one psychological and the other physical: triggering severe stress (especially when people are displaced) and prompting mold outbreaks, a common result of flooded homes.

Parks and green spaces improve urban environments by other methods, too. They improve air quality—reducing levels of particulate matter and other pollutants. They reduce people’s exposure to noise such as that from urban traffic—an underappreciated health threat. And large parks may be the only places in cities where nighttime light pollution is at least somewhat avoidable, enabling people to stargaze. Through these many pathways, both direct and indirect, implementing and supporting parks and green spaces is a powerful public health strategy.

Free fitness classes are offered by the New York City parks department through a program called Shape Up NYC. A hundred different exercise and dance classes are held each week in a wide range of locations. Photo: NYC Parks/Daniel Avila

Park agencies across the United States are working to break down barriers—including those related to economics and access—to allow residents to connect to health-giving parks and park programs. Increasingly, cities are partnering with hospitals and health insurers on innovative programs to provide and pay for fitness classes, both indoors and out. Park agencies are also teaming up with nonprofit groups to ensure that all residents, regardless of age or ability, can access green spaces that hold the potential to promote physical and mental health.

The opportunities to leverage the health-boosting potential of parks, community gardens, and recreation centers are seemingly endless. In New York City, for example, a program called Shape Up NYC offers free classes in everything from yoga to Zumba to Pilates in easy-to-access locations: libraries, public-housing complexes, recreation centers, and, of course, parks. In Aurora, Colorado, some of the state’s lottery revenue goes toward promoting outdoor activities like kayaking and hiking among communities with the least access to green space.

In Columbus, Ohio, doctors at a local hospital prescribe 11-week fitness programs, provided for free by the city’s parks department, to patients struggling with obesity and high blood pressure. And in Chicago, a community garden served as a lifeline during the pandemic for senior residents who would have otherwise been isolated from one another.

Young campers from Commerce City, Colorado, prepare to kayak at Aurora Reservoir through a program called Generation Wild. Photo: Joy Thompson

To better understand how common these emerging strategies are across the country, Trust for Public Land conducted a survey among the 100 largest cities as part of its annual ParkScore index. These cities collectively shared nearly 800 examples of what they consider to be their most effective ways of using their parks and recreation systems to promote physical activity, improve mental health, and increase social connections.

While the COVID-19 pandemic underscored how health professionals, residents, and city leaders turned to park systems in times of emergency, these findings tell a new story. “We’ve always known parks are good for health and that recreation agencies host sports leagues and fitness classes,” says Diane Regas, president and CEO of Trust for Public Land. “But today, we’re finding that city park systems are thinking of themselves a bit differently—they’re stepping up and delivering for health in new and surprising ways.”

There are many places, especially in urban environments, where residents don’t enjoy effortless access to nature— where children cannot simply walk to the woods to climb trees or get to a creek to look for salamanders or try their hand at fishing. In those cases, park agencies can step in to create new parks near where people live. And they can make arrangements to connect residents with the natural world.

Such is the case in Aurora, Colorado, where the Department of Parks, Recreation & Open Space is part of a regional coalition that seeks to introduce young people to the great outdoors through a program called Generation Wild. It’s funded through Great Outdoors Colorado, the state lottery, which several years ago identified communities across the state where residents spent little time in nature.

Aurora teamed up with the Cities of Denver and Commerce City, along with several nonprofit groups, to apply for a grant to address this so-called nature deficit. With funding in hand, the cities targeted four communities across the region where 85 percent or more of public school students receive a free or reduced-cost lunch. “They were predominantly communities of color and communities that are economically more depressed,” says Joy Thompson, Aurora’s natural resources supervisor. “In our city, we focused on northwest Aurora, which has a large refugee population.”

On weekends throughout the year, the three cities arrange outings for groups of young people to participate in archery, kayaking, fishing, and biking. The coalition covers the cost of bus transportation; lunch and snacks; and all equipment, including fishing rods, kayaks, and bicycles.

Thompson says she has watched teenagers unwind on a slow-moving river, amid stands of Douglas fir, or while exploring rocky ledges. “We have immigrants from Bhutan, Myanmar, Africa, and other areas experiencing pretty intense conflict,” she observes. “Trying to make friends, navigate the school system, learn English—this gives kids a break from all that. We see them visibly relax. Definitely the mental health benefits are there.”

Programs like Generation Wild are emerging across the country as an effective strategy to increase park access and usage. In our survey of the 100 most populous U.S. cities, 30 reported that they offer an outdoor outings program or organize neighborhood walks to connect people, especially youth and seniors who may lack a nearby safe park, to the outdoors.

Eighteen of the 100 cities are essentially implementing this strategy in reverse. They are bringing park experiences to where people are, whether that’s a virtual reality nature hike from a hospital bed or bringing a climbing wall to a community space without one. Meeting people where they are and taking people to nature are both effective strategies for parks and recreation agencies to build relationships with those who otherwise may have felt excluded from parks or green space, and thus not able to get their full dose of nature. Meanwhile, 24 other cities reported efforts to address another critical barrier to park access: cost.

In Saint Paul, Minnesota, the parks and recreation department targeted its sports leagues with a goal of boosting participation and health equity, specifically cardiovascular and mental health among young people. The solution: drop all fees. Andy Rodriguez, director of Saint Paul Parks and Recreation, says the department had watched enrollments fall over the past five years in sports such as volleyball, basketball, and soccer.

Tapping money from the federal American Rescue Plan, Saint Paul plans to waive all sports-league fees for at least three years. (Typically, registration fees run about

$55 a child per season.) The results were impressive: last year, soccer registrations rose by 95 percent from the previous year, and basketball by 108 percent.

“It levels the playing field,” Rodriguez says. “To some, $55 might not mean a lot, but for other families, that’s a decision. Do I want to use the funds for my child to play a sport, or do I use that money for a necessity? This eliminates that decision. The health outcomes and the ability for young people to build relationships are so positive.”

Financial barriers to physical exercise were a main impetus for New York City’s popular, long-running fitness program Shape Up NYC. But so, too, were geographic obstacles. Despite the fact that NYC Parks oversees a veritable empire of parks, playgrounds, and recreation centers, the department decided to expand its free fitness classes to all kinds of locations. That means residents can do Pilates at the local library, take an aerobics class in a health clinic, try Zumba in a public-housing complex, sign up for boot camp at a nearby high school, or join a group walk in a park.

Kendra Van Horn, director of Citywide Fitness for NYC Parks, says the fitness offerings—most of them held indoors—fell sharply during the pandemic but have started to rebound, with more than 100 classes held each week in 80 facilities across the five boroughs. To eliminate other hurdles, there are no income requirements, and registration is optional; participants can just show up. In the past year, the fitness program hosted 5,000 visitors, including repeat participants. Most were women of color, and the average age was 55.

“Lack of access in one shape or form is the number one thing that prevents people from getting regular fitness,” Van Horn says. “It could be financial access or physical access—it’s not convenient, it’s not in their neighborhood. So we have tried to eliminate both of those barriers.”

Robin Badger, who lives in Brooklyn, has taken free Shape Up classes through her local recreation center for the past few years. The 60-year-old retiree had gastric bypass surgery in 2021, shedding more than 125 pounds. The twice-weekly fitness classes, she says, have helped her maintain the weight loss and build muscle.

A visitor works out in Azalea Park in St. Petersburg, Florida. The park’s wheelchair-accessible Fitness Zone® allows people of all abilities to participate in strengthening exercises. Photo: Courtesy of Greenfields

Outdoor Fitness

Centered on aerobics and stretching, the classes are also a boon for her mental health. “There are a bunch of us who meet up in the class and afterward we go to a quilting class,” she explains. “I feel good when I get home, just relaxed. I miss it when I don’t go.” The annual budget for Shape Up NYC—around $300,000—is covered by a patchwork of public and private sources, including the parks department, the mayor’s office, private foundations, and Empire BlueCross BlueShield, the largest health insurer in New York State. Van Horn says Empire has provided grants totaling $2 million over the past decade, a significant contribution.

While the program relies largely on volunteer instructors, many are paid. Shape Up NYC even offers a free 12-week training program for people who want to become fitness teachers. “A lot of people use it as a foot in the door to start a fitness career,” Van Horn explains. “Most of the instructors I’ve hired have come up through that program. We have 16 paid instructors right now.”

Some cities, like Columbus, Ohio, have formed more direct partnerships with the healthcare industry. In 2019, the city’s Recreation and Parks Department joined forces with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in a program called Exercise is Medicine. The program is part of the American College of Sports Medicine’s global initiative to make physical activity a standard part of disease prevention and treatment. Through the Columbus program, any doctor within a healthcare system in the metropolitan area, regardless of specialty, can write prescriptions for exercise as part of a patient’s treatment plan.

“The philosophy of the program is to intervene before mild things like joint problems or prediabetes or obesity turn into chronic illnesses,” says Bryana Ross, the city’s recreation administrative coordinator.

Patients who receive an exercise prescription enroll in a free 11-week fitness program offered at Beatty Community Center, one of 28 such centers that the Recreation and Parks Department operates. (Wexner Medical Center offers a similar program at a YMCA in the city.) Ohio State provides funding for the program, including staff time and equipment.

Twice-weekly classes are offered in cardio, strength training, and aerobic exercise, with class sizes capped at six to eight students to allow for plenty of individual attention. Throughout the program, a staff member monitors participants’ weight, BMI, and blood pressure, reporting outcomes back to their physicians.

Twice-weekly classes are offered in cardio, strength training, and aerobic exercise, with class sizes capped at six to eight students to allow for plenty of individual attention. Throughout the program, a staff member monitors participants’ weight, BMI, and blood pressure, reporting outcomes back to their physicians.

“Exercise is Medicine and similar community health programs are essential to reducing barriers to exercise and improving a community’s overall health and wellness,” says Allan Sommer, the wellness program manager at Wexner Medical Center.

Frumkin agrees. “Hospital systems ought to be donating funds to maintain parks as healthy places,” he notes. “This is an appropriate and noble way for hospitals to spend their community health dollars. We need more programming to reach groups that would particularly benefit: elders, people who live alone, people with disabilities.”

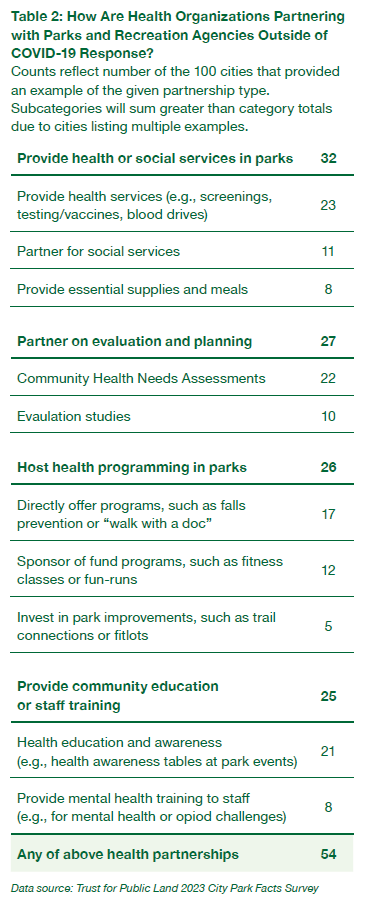

In a growing number of cities across the country, healthcare institutions—insurers, hospitals, and public health departments—are funding programs in parks, as well as park improvement projects, to improve patient and community health. Yet at the same time, our survey revealed that these programmatic and financial partnerships are happening in only 26 of the 100 largest cities, suggesting that parks remain an underutilized strategy in the health sector’s toolbox. It is still more common for parks and healthcare institutions to partner on planning efforts or direct health services than programmatic ones (Table 2).

Increasingly, cities are looking at the health potential of their parks through another lens—that of disability. If children cannot climb on play equipment and adults cannot make their way around a walking loop, they won’t reap the health benefits available to others. While the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) lays out some design requirements, people in the disability community say those standards are inadequate.

Trust for Public Land has worked with a number of landscape architects and trail designers determined to make outdoor spaces accessible for all. At the newly renovated Panorama Park in Colorado Springs, Colorado, for instance, we enlisted Kerry White, a landscape architect and principal of Urban Play Studio, to design the play areas. “The whole idea behind universal design is that it’s conceived in a way that’s better for everyone, no matter your ability,” says White.

Panorama Park is packed with such amenities. There are a variety of accessible swings, a sand table that children in wheelchairs can access, and a Quiet Nook for anyone who might need a momentary escape from the stimulation. Contrasting bands on the rubber play surface serve dual purposes: They define, connect, and organize various play stations for neurodivergent children who need visual cues to guide their play journey. They also help guide people with visual impairments.

About a decade ago in Greenfield, New Hampshire, Trust for Public Land partnered with a foundation to create a wheelchair-friendly trail that winds through wetlands and grasslands before rising to a summit. The accessible trail achieves its elevation gain through a series of switchbacks, along with pull-off areas for resting.

The nonprofit partner on the trail had operated a school and treatment center—now owned by the Seven Hills Foundation—for children and adults with a variety of disabilities. The project also protected 1,200 acres adjacent to the campus through a conservation easement, preventing future development and guaranteeing public access.

Sometimes it’s the most unassuming spaces that have the biggest impact on residents’ lives, especially when that space is right outside their front doors. Take El Paseo Community Garden in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, a predominantly Latinx community alive with music, art, food, and nightlife. The garden is protected by a nonprofit land trust called NeighborSpace, which receives financial support from the City of Chicago and Chicago Park District.

Students take a basketball break at Markham Elementary School in Oakland, California, where Trust for Public Land transformed a concrete schoolyard into a vibrant play space with a soccer field and 75 new trees.

Photo: Amy Osborne

Bordered by a cluster of affordable-housing apartments, including one exclusively for senior citizens, El Paseo Community Garden is open to the public 24 hours a day. The garden is just one acre but keeps local residents active with a wide variety of programs. Among the activities are gardening; beekeeping; barbecuing; nature play; senior programs; weekly classes in yoga, meditation, flamenco, and fitness; and monthly clinics featuring acupuncture and massage.

“We actually thrived during the pandemic because people had the time to volunteer—so many were out of jobs,” points out Paula Acevedo, who is codirector of the community garden along with her husband, Antonio. “We had a lot of donations as well. The garden is still a safe haven for so many folks. It’s a community backyard, and we take care of it together.”

For residents like Carlos Nunez, the garden is a pleasing reminder of his home country of Mexico—a place to bring a guitar, strike up a conversation, and maintain social ties. “The garden has given me life,” he says during a video about the outdoor space. “I used to be a very depressed person because I didn’t have much to do. And when I came here and started to get involved, I was reminded of my youth in a little town named Los Herreras in Durango where we cultivated fruits and vegetables. Then all of that started to vanish—the depression and all. And that’s why I’m here.”

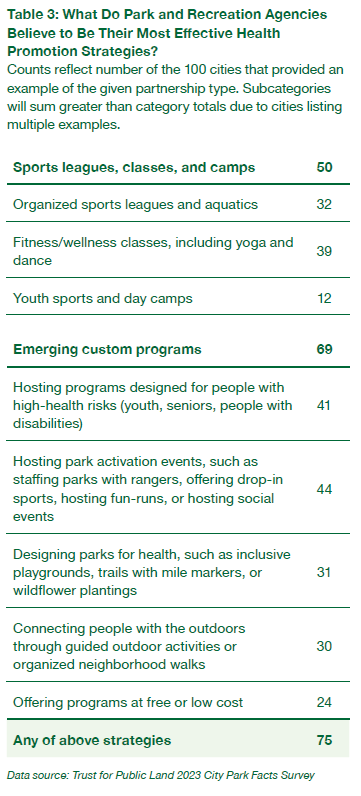

Across the country, cities are reimagining gathering spaces, like El Paseo Community Garden, as venues for community groups to connect and address growing rates of health issues such as loneliness, anxiety, or depression. Last fall, we asked parks and recreation agencies across the 100 most populous U.S. cities what they considered to be their most effective programs at improving physical and mental health. While a majority of agencies did name either a camp, sports league, or fitness class, we were surprised to learn that a greater number of agencies identified something other than those three typical offerings.

These emerging custom program offerings reflect the growing understanding among parks and recreation professionals that one of the primary drivers of an individual’s park use is the activities they want to be associated with at a given park. By explicitly designing programs for people who haven’t always seen themselves as an athlete or fitness buff, agencies are finding ways to increase participation rates, and thus improve health, among new audiences (Table 3). What this looks like in practice is beautiful—an expanding kaleidoscope of people engaging in healthful activities, from kids trying out a magnifying glass or adults running with friends for the first time.

These emerging custom program offerings reflect the growing understanding among parks and recreation professionals that one of the primary drivers of an individual’s park use is the activities they want to be associated with at a given park. By explicitly designing programs for people who haven’t always seen themselves as an athlete or fitness buff, agencies are finding ways to increase participation rates, and thus improve health, among new audiences (Table 3). What this looks like in practice is beautiful—an expanding kaleidoscope of people engaging in healthful activities, from kids trying out a magnifying glass or adults running with friends for the first time.

Some doctors, too, are acting on their own to boost patients’ exposure to nature. Dr Tandon, the pediatrician in Seattle, recently worked with colleagues on a pilot program called Project Nature During regular checkups, young patients and families received a brochure explaining the benefits of being outdoors and ideas for activities, along with a small age-appropriate toy or tool like a shovel or magnifying glass.

“We have done it in just a handful of clinics in the Seattle area, but the goal would be to show that it is effective and scale it up,” Tandon says. “Both the providers and families really liked it and thought it was useful.”

Nonprofit organizations, too, have a role to play in promoting outdoor activity, health experts say. Girls on the Run, an organization active in the United States and Canada, seeks to spark the joy of movement in girls in elementary, middle, and junior high school. Its broader goals include helping girls develop social, emotional, and physical skills; encouraging healthy habits; and instilling confidence.

Ronda Lee Chapman, Trust for Public Land’s equity director, was a volunteer with Girls on the Run in Washington, DC. She recalls escorting students safely from their charter school, which had no outdoor space, through a busy urban environment to access nearby green spaces where they could practice running. “It brought home why we need parks so desperately—if we want these girls to have a healthier lived experience,” she says.

The highlight for Chapman was the culminating race in May, where members of dozens of Girls on the Run chapters in the capital gathered in Anacostia Park, a 1,200-acre green space operated by the National Park Service. The park is on the Anacostia River, which divides DC in two. The west side of the river is largely prosperous, Chapman points out, while the east side is politically and economically underinvested, resulting in “numerous disparities despite the generations of mostly Black families that show up for the community daily.”

“When this event takes place at Anacostia River, several things happen in my mind, and one is the way the park becomes alive,” Chapman says. “The other thing is the multiracial interaction that occurs among these girls who wouldn’t otherwise connect; they are all just there to run. It’s such a beautiful thing. The park becomes a bridge for these young people.”

Recommendations: 14 Practical Ways Cities Can Address Emerging Health Crises through Their Parks

While we know parks are good for health, they deliver health benefits only when people visit and use them. Through our research, we identified two emerging trends. First, parks and recreation agencies are reimagining what park access looks like to reach new audiences. And second, while health institutions are starting to test the waters of incorporating parks into their health promotion strategies, there is immense untapped potential. Imagine what could be achieved if we doubled down on using parks as a frontline strategy to address the growing range of chronic health problems facing urban residents across the country.

In our ParkScore index survey, we collected nearly 800 examples of how cities are using parks to promote health. From these suggestions, we’ve identified 14 of the most practical that also have the highest potential for impact.

The strategies centered on three core principles:

- Ensure that everybody has access to parks and natural areas where they feel welcome.

- Make parks as health-promoting as possible.

- Bring on the partnerships! Deploy the resources, expertise, and energy of the health sector to promote all of the above.

Within these 14 strategies, we think you’ll find realistic options for every place and situation. We challenge you to pick at least one and try it this upcoming year.

When people are able to spend time in parks, it benefits their health. Yet over 100 million people across the country, including 28 million kids, don’t have a park within a 10-minute walk of their home. In California, for example, 42 percent of low-income parents report that their children have never participated in outdoor activities. Kids growing up in places like San Francisco may be so isolated from their natural environment that they’ve never seen the Pacific Ocean. One of the most straightforward ways to improve the health of your community is to ensure that everybody has a way to connect with the outdoors, including both nearby parks and access to larger destination parks or natural areas. These are four of the most promising strategies to increase access to parks, which in turn promotes health:

Park agencies are installing walking loops and paved paths to accommodate walkers, joggers, cyclists, and even longboarders—like Faviana Gaspar in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Photo: Brooke Bragger Photography

1. Ensure that everybody lives within a 10-minute walk (about a half mile) of a park. Protecting and sustaining existing parks, adding new green spaces, and ensuring parks are core to new developments or redeveloped areas—in any market—and are essential for providing access to nature and outdoor experiences. When there are not readily available or feasible opportunities, consider partnering with other agencies such as schools, utilities, or libraries to unlock green spaces in nearby public areas. Also consider that quality, activation, and safety are part of ensuring the success of a park or green space. To activate new public places, work with local community leaders on creative placemaking initiatives that incorporate local character through cultural elements such as public art and bilingual signage.

2. Prioritize capital improvements and engagement with communities that have been historically underserved. In most cities, there are fewer or smaller parks in neighborhoods of color and low-income communities, which are often the places that have been systematically disinvested in through redlining or other forms of discrimination. In some cities, where funding is primarily allocated to improve existing park sites, this can perpetuate a pattern of disinvestment in neighborhoods with smaller or fewer parks. One way to address this is to ensure funding is designed to address historical inequities—and that community perspectives are centered in these decisions.

3. Bring people to your parks and natural attractions through transit connections and guided trips. To connect people to the outdoors, invest in both the physical infrastructure (e.g., transit routes) and the social infrastructure, such as guided youth programs, to make it possible for all residents to enjoy your region’s cherished places. To ensure there are great natural areas to visit, continue investing in protection and creation of parks and green spaces through innovative approaches such as transforming golf courses or incorporating recreational elements into large utility-owned lands.

4. Bring parks to the people through pop-ups and mobile offerings. As a short-term strategy to improve the quality of existing parks or as a way to test new ideas, develop a mobile recreation program that brings activities to neighborhoods and existing parks that lack them. In some cities, parks departments have taken this a step further, bringing fitness classes and virtual reality hikes to other settings, such as hospitals, schools, and community centers.

One of the biggest barriers to spending time outdoors is the feeling that a park just isn’t for you. “Jo,” a Baltimore woman interviewed for a study investigating the importance of social access, explained why she doesn’t feel able to walk at her neighborhood park: “It’s fenced in for football. That’s all you got it’s not inviting for somebody to say, ‘OK, let’s go over and exercise ’” The parks and recreation agencies in the 100 most populous U.S cities were more likely to cite something other than a sports league, fitness class, or camp as one of their agency’s most effective programs to improve physical or mental health The emergence of custom health programming in parks comes from the need to ensure that people like Jo, who don’t see themselves as football players, feel like they have a place to go for a walk.

Boys in Saint Paul, Minnesota, compete in volleyball in one of the city’s free sports leagues. Saint Paul used money from the federal American Rescue Plan to waive all fees for at least three years. Photo: Saint Paul Parks and Recreation

These four recommendations reflect the most promising strategies emerging across the country from parks and recreation agencies which are redesigning their programs and spaces to both encourage new park visitors and increase healthy activities once somebody gets there.

Collectively, these strategies target common barriers to physical activity and address one of the CDC’s main recommendations for improving mental health via social connection:

5. Offer all-ability or “try before you buy” fitness and wellness programs explicitly designed for beginners.

This program design addresses a common barrier to participating in fitness classes—the feeling of nervousness or intimidation in trying something for the first time. Parks and recreation departments such as the one in Saint Paul, Minnesota, are also expanding efforts to address another common barrier, affordability, by finding sponsors such as health insurers or grants to fund registration costs.

6. Encourage park visitors to try something new with low-commitment offerings such as drop-in sports (e.g., adult recess) or free or low-cost gear rentals. Sometimes all it takes is someone asking if you’d like to try something to ignite a newfound passion. Familiar faces can help, too: “train the trainer” models, such as New York City’s Shape Up NYC program, teach residents to lead fitness classes and prepare local youth leaders to take peer groups on outdoor excursions such as camping trips. Consider joining a growing network of cities that provide gear libraries where users can borrow hiking boots, sleeping bags, and tents.

7. Make it easy for community groups to use parks and recreation facilities as their primary gathering venues. In many cases, parks and recreation agencies don’t have to develop or run programs; they simply have to provide a safe, comfortable, welcoming place for groups such as Girls on the Run, teen mentors, senior meetups, or the Special Olympics to gather and build social connections. A growing number of agencies are developing grant programs or finding sponsorships for facility use to make it even easier for community groups to take advantage of their cities’ terrific park systems.

8. Install and maintain the amenities most strongly associated with increased physical activity. These include sport fields and courts, walking loops, fitness zones, playgrounds, splashpads, and trails. Small design features, such as adding mileage markers to trails or educational signage to other amenities, can further encourage the use of facilities for physical activity. Don’t forget to incorporate shade, natural features, and placemaking elements.

Across the country, healthcare institutions—hospitals, insurance agencies, and public health departments—are elevating local parks and recreation facilities as a frontline strategy to help their patients (and themselves) struggling with chronic challenges such as obesity, loneliness, trauma, stress, or anxiety. This reflects an emerging shift in the notion of a park’s role in the healthcare toolkit. First, parks and recreation facilities emerged as one of the most trusted places for public health agencies to address the COVID-19 pandemic through distribution of vaccines, tests, and meals. And today, we are seeing parks adopted by a growing number of insurance companies and physicians as a key strategy for delivering a wide range of evidence-based approaches to addressing chronic public health concerns.

Across the country’s 100 most populous cities, these six strategies emerged as the most promising for healthcare organizations that want to incorporate parks into health promotion activities:

9. Refer, prescribe, or host patients with health programming in parks and recreation facilities. For residents intimidated by trying something new, a gentle nudge from their doctor and a prescription to spend more time outdoors can be surprisingly motivating. For others, a healthcare professional offering to lead a walk or fitness program can be the tipping point to getting outside. Doctors, nurses, and healthcare staff likewise benefit from leading walks and encouraging conversation with patients about current health topics, taking questions, and promoting healthy living.

10. Sponsor the costs of wellness programs, sports leagues, and other health classes as part of any free fitness membership benefit. Across the country, a wide variety of health insurance plans offer free or reduced-cost memberships as part of their preventive services benefit, such as SilverSneakers, a health and fitness program designed for adults ages 65 and older that’s included with many Medicare Advantage plans. In our research, parks and recreation agencies repeatedly cited free or low-cost programming as one of their most effective strategies for improving physical activity. Insurers should reach out to parks and recreation agencies to learn about and include such classes at low or no cost to their members.

11. Invest in capital improvements in parks as community health investments. As a complement to patient-centered programming, health insurance foundations and hospitals are investing in park and trail facilities as part of their efforts to address the underlying social determinants to health (e.g., the oft-cited statistic that a person’s zip code can be a better predictor of health than their genetics). Across the country, five cities are leading the pack, partnering with healthcare institutions that are funding park improvement projects, such as building trail connections to hospitals in Des Moines, Iowa, or investing in amenities like an AARP FitLot Outdoor Fitness Park in New Orleans, Louisiana. Who will be next?

12. Work with parks and recreation agencies to map and identify park deficits as part of Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNA). As one of the requirements of the Affordable Care Act, all nonprofit hospitals are required to conduct these assessments every three years. Many CHNAs identify mental health or obesity as critical health needs facing their communities, but relatively few call out parks as a way to address those needs. Across the country’s 100 most populous cities, 22 reported that their parks and recreation agency is partnering for a Community Health Needs Assessment. In most cases, these partnerships are aimed at coordinating efforts to understand community needs. In cities where parks have been identified as a community health priority, the hospitals are able to use their community benefit funds to invest in health programming or amenities in parks.

13. Continue to partner with parks and recreation agencies to reach key patient populations with health services and education. From COVID-19 response to supporting those living in parks, parks and recreation agencies are increasingly providing social and health services to at-risk patient populations. Health institutions can build upon successful pandemic response coalitions by partnering with agencies to offer health screenings and services such as health education and awareness classes. In many cities, health institutions are also supporting parks and recreation agencies by providing staff training on how to address emergent health needs from park users beyond first aid and CPR.

14. Partner with parks and recreation agencies to evaluate the impact of park initiatives on key patient and community health outcomes. While it is widely understood that parks improve health outcomes, there remains a gap in healthcare institutions seeing parks and health programming in parks as an evidence-based treatment for patients and communities. Partnering to evaluate and understand which types of programming and park investments drive the biggest gains in health outcomes would help close this gap.

A group hike in the San Gabriel Mountains in Southern California. Photo: Annie Bang

Conclusion

Park agencies of all sizes are stepping up to make parks as health-promoting as possible. But more can be done. Making sure residents have easy access to parks is critical. So, too, is making those spaces appealing and inviting to everyone. Offering a boost—such as free fitness classes, amenities that get people moving, and features such as water fountains and bathrooms— encourages users to stick around and come back often.

Similarly, other city agencies—whether transportation, sanitation, or planning—should take a close look at parks to make sure they are available and hospitable to all. How might public transportation make it easy for people to get to parks? Can porous boundaries be created so that people can enter parks near where they live? Are parks free of trash and in good condition? Do people of color and immigrants feel like they belong?

“All of the soft signals that tell people the park is safe and welcoming should be attended to,” Frumkin says. “That means inclusive programming and art installations and cultural events that make all groups feel welcome.”