“There’s no substitute for being able to tell your own story.”

“There’s no substitute for being able to tell your own story.”

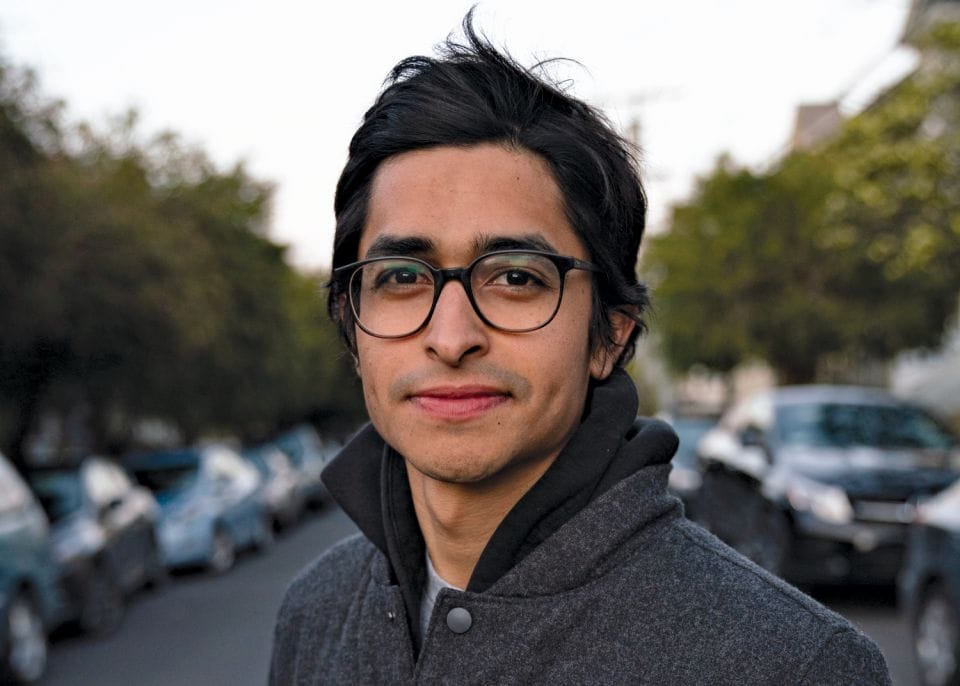

Journalist and photographer Michael A. Estrada doesn’t shy away from the big questions. And right now the biggest question driving his art and work is how our relationship with nature—and our self-perception—are influenced by the mainstream depiction of the Great Outdoors: an esoteric realm, far from home, requiring fancy gear … and mostly inhabited by white people.

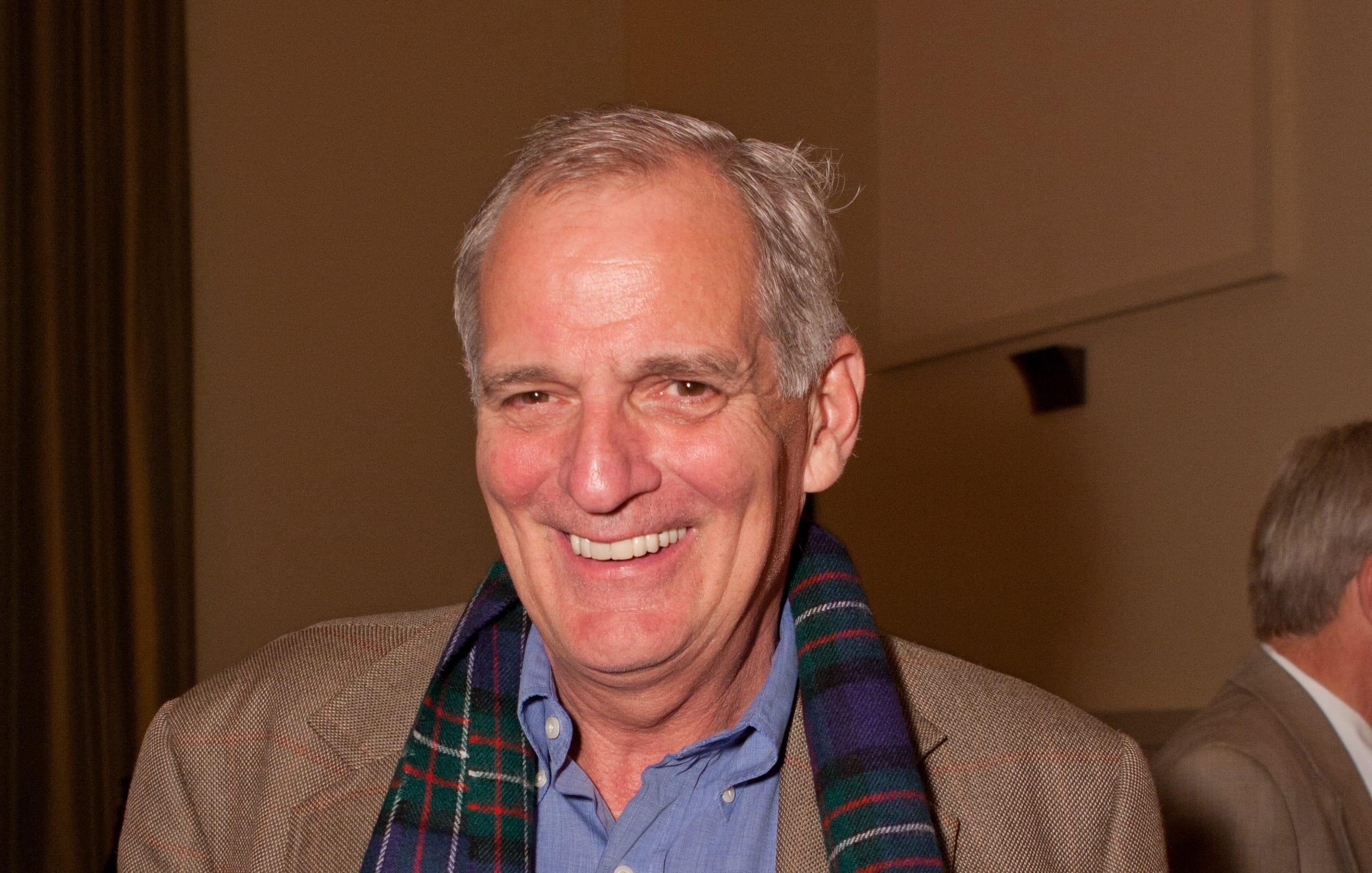

“Our society has an imagination gap,” says writer and photographer Michael Estrada. “How do we see ourselves? How do other people see us?”Photo credit: Teresa Yu

“Our society has an imagination gap,” says writer and photographer Michael Estrada. “How do we see ourselves? How do other people see us?”Photo credit: Teresa Yu

People of Color and Indigenous People are and have always been profoundly connected to nature, Estrada thought … why aren’t our stories being told? Recognizing a need to shift the narrative, Estrada launched Brown Environmentalist, a multimedia project chronicling the contributions of people of color in conservation and environmental justice movements. Through the project, Estrada has made it his mission to “uproot and replace traditional environmental thought with narratives that acknowledge Black, Indigenous, and people of color as the leaders and caretakers of the environment, amplify the content that already exists, and create what doesn’t.”

You can find Estrada’s work on social media using the hashtag #BEEN. We caught up with him to hear more about the stories he’s helping to tell.

You started a storytelling campaign on social media, “to celebrate the different and many ways that Black, Indigenous, and People of Color have spent time in the outdoors.” You asked a couple questions to kick things off, and we wondered how you’d answer them: “How has your family historically #BeenOutside?”

I started that conversation after I unearthed some old family photos from El Salvador, where both of my parents grew up. I know my grandma raised chickens, and had to get her water from a well— it made me realize she was probably by necessity way more connected to nature than I’ve ever been. But in these old photos, my grandma is standing on top of La Puerta del Diablo, a mountain near her home in El Salvador. In that picture, I see proof that I am connected to past generations of my family through nature, that they likely enjoyed the same things I do now, that our separate stories could cross paths in how we touched nature, or how nature touched us.

“How have you #BeenOutside?”

My experience of the outdoors has been a lot different from my family’s experience. In part I think that’s because my parents emigrated from a country where spending time outside was not necessarily a luxury … coming to the U.S. and pursuing education was a way to not have to work outside.

Mainstream outdoor media have tended to portray this idea that a remote wilderness is better or more valuable than a city park or the garden between the sidewalk and the street. But I rarely had wilderness experiences growing up. As a kid, most of my time outside was in a park, surrounded by buildings and noise, or playing soccer in the driveway. I don’t remember ever setting foot on a trail until high school cross country practice, and “hiking” didn’t enter my vocabulary until college: a friend invited me on a hike, and I was like, “What’s that? You mean we’re just going to walk to the top of something?”

n the coming months, we’ll use our powerful data and analytics to help communities understand the climate threats they’re facing, and identify the park and open space investments that can help them withstand disasters.Photo credit: Annie Bang

n the coming months, we’ll use our powerful data and analytics to help communities understand the climate threats they’re facing, and identify the park and open space investments that can help them withstand disasters.Photo credit: Annie Bang

I don’t ever want to be limited by what someone else tells me is a “true outdoor experience”—like, it only counts if you get far enough from the city, or if you can make it so far on a trail, or if you’re carrying a certain kind of backpack. Once you start assigning different values to outdoor experiences, or even just putting specialized words like “hike” on them that might not resonate with people who didn’t grow up with access, it makes the outdoors more exclusive, and that is a barrier. Maybe not a physical barrier, but a mental barrier to everyone getting to experience the outdoors.

So for me now, whether I’m biking around the city or heading out to the woods, anytime I’m outside, it counts.

Why did you launch Brown Environmentalist?

So much of what we think of the world is based on what we see in the media. Whether you’re watching the Oscars, reading the newspaper, or following outdoor industry media—most of it is produced and controlled by white people.

I’ve been sharing stories about Brown and Black outdoor athletes, activists, and organizers, because yes, we need more diverse representation in media. But I’m also always looking to put athletic feats into the context of what it means to be a person of color in this space, and in this country—what it means to their families and communities, how it relates to our history.

Why is it important that Brown, Black, and Indigenous people be represented in the media—not just as the focus of stories, but as storytellers?

Even if you are putting people of color on the cover of your magazine, even if you are bringing people of color in as employees at your company or organization, it’s still mostly white people doing the inviting, holding the power, and controlling the narrative. Brown and Black people are constantly asked to fit into a white narrative and structure. As a person of color, it’s exhausting to operate solely in that “diversity” space, where white people are in a position to invite Brown and Black people in, but not really giving up any of the power. Most often, I see diversity applied as a Band-Aid, instead of doing the real, hard work to change a broken system.

I’m focusing my energy on organizations led by people of color who are already here, doing great work around environmental issues, and especially issues of environmental justice. It’s not hard at all to find people of color whose stories can drive change and deserve telling, but their stories never get amplified. While I’m interviewing people, they’ll start to reflect and go, “Huh, I guess my story is cool,” and I’m like, “Yeah, you’re getting way more done than most people out here, and you’ve been doing it for years, and nobody knows!”

Photo credit: Michael Estrada

Photo credit: Michael Estrada

“Jolie Varela is from the Yokut and Paiute Nations,” says Estrada. “She leads Indigenous Women Hike, a movement to help women in her community reconnect with the land. Her approach is genuine and focused on her community. She’s using her voice and the lens of the land to bring awareness to issues that affect Indigenous people all over North America. Here, she’s at the front of the Rise for Climate March last fall.”

Social media has democratized storytelling by light years, but the world of mass media is still very exclusive. That’s why I create media that’s Brown and Black focused, and why more people of color are starting groups around spending time together outdoors, or starting their own media platforms. We’re trying to completely take something apart, start anew, with a different structure.

What aspects of the environmental movement most need to be taken apart and started anew?

The legacy of environmentalism contains philosophies that are the antithesis of Brown and Black people living well. Take the idea of “wilderness”: well, first you removed all the Native people from that land. But that history never entered any of the environmental studies courses I took. I learned a lot about, like, trash and pollution, and what a great environmentalist John Muir was, but there was never anything on Indigenous history and uses of the land, or discussion of their removal.

That just really doesn’t make sense to me! People of color are the original environmentalists, the original eco-warriors, but the narrative I got growing up was all about white Americans’ history, voice, and thought. If our history hadn’t been erased, you’d hear much more about the environmental movements led by people of color—and women of color, specifically.

What’s an example of that erasure?

Take the term “tree hugger.” I bet anyone who’s identified as an environmentalist has, at some point, called themselves a tree hugger—whether proudly or with little self-deprecation. But how many people have the backstory? In India in the 1700s, soldiers representing Maharaja Abhai Singh ordered a forest near a village named Khejarli to be cut down for a new palace. Villagers stood in front of the trees to protect them, so soldiers just killed them. This continued until over 300 people were dead, at which point the maharaja relented, and the forest was saved.

In the 1970s, that history inspired nonviolent protests against deforestation in Northern India. For years, women took turns guarding trees day and night, until the Indian government ceased logging in the area. The progress these women made—which came to be called the Chipko movement, meaning to hug or embrace—directly informed the actions of anti-logging activists in the U.S. and Canada in the 1980s.

Those were the folks who gained a sort of fame for sitting in trees and standing in front of bulldozers?

Yes. That’s the image I think most people get when they even stop to consider where the term “tree hugger” comes from. But those people took their lead from the Chipko movement, which took its lead from Khejarli. This is the kind of story I want to keep telling, because it asks people who’ve already proudly claimed some identity as environmentalists to go back and question, and learn more about what exactly it is they’ve claimed.

Photo credit: Michael Estrada

Photo credit: Michael Estrada

“Faith Briggs is a trail runner based in Portland, Oregon,” Estrada says. “I’ve noticed her humble approach to both life and people from the beginning. Through her always-stoked mannerisms and happy face, it’s easy to feel like you’ve known her your entire life. She told me about a few of her experiences as a biracial woman of color, as an athlete and creative who has faced injury and disappointment, and as a human being who, through humor and a positive attitude, always keeps her head up.”

Until folks of color and marginalized people in general control their own narratives completely, we’ll always be in some way exploited, misrepresented, or tokenized. In the end, there’s no substitute for being able to tell your own story.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.