Trail-work tales from an Appalachian expert

Trail-work tales from an Appalachian expert

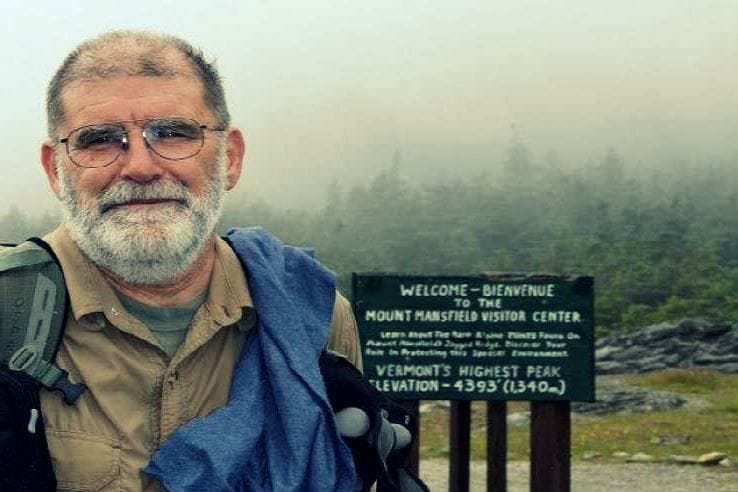

If there’s anything we appreciate more than the Appalachian Trail, it’s the dedicated volunteers who maintain it. Jim Sullivan is one of them. In August of 2013, he was working on a stretch of the trail that runs through Stamford, Vermont, when he came across a “For Sale” sign in the trailhead parking lot.

Jim knew that this mile-long segment of trail was poorly protected: the easement covered just 100 feet on either side of the trail. So he alerted local conservationists. When the 384-acre property went up for auction, The Trust for Public Land was able to secure it—and a few months ago, we succeeded in adding the land to the Green Mountain National Forest.

We caught up with Jim to hear more about the often unseen efforts to protect the Appalachian Trail experience.

Q: What do you think is the value of protecting the land and views surrounding trail?

A: Priceless. It’s absolutely priceless that this land was preserved. The wilderness experience gives you a view back on what our forefathers saw: a real, natural environment. It lets people reconnect with nature.

Q: How did you get into trail maintenance?

A: I’ve hiked all my life, and I’m always picking up junk off the trail whenever I see it. So after I retired in 2008, I started volunteering with the Green Mountain Club on the segment that was just protected. It’s heavily used: it’s home to the Seth Warner Shelter, which is the first shelter that thru-hikers come to in Vermont. By 2012, I was volunteering 600 to 700 hours in the summer.

Q: What kind of tasks do you do?

A: In the spring, you try to clear out all the downed branches and trees that have fallen across the trail over the winter. Then you attempt to restore or provide drainage to get the water off the trail. These days I also help maintain outhouses, and I make maps for trail relocations. This summer, the crew will be finishing up a trail that I’ve spent several years exploring and planning.

Q: Wow, several years?

A: Oh, yes. You have to lay out a path, put a flag line in, and then the Forest Service has to review it. They send out a botanist, a biologist, and an archeologist. Sometimes the state has to approve it. Basically, any trail relocation is pretty much a five-year project.

Q: Do you see issues with overuse on the trail?

A: Sometimes. On a nice weekend, the shelter gets overloaded and there are people camping all around it. I’ve seen 15, 20, or even 25 people there, which is way more than the place was ever intended to hold—so you get trampled ground and brush, people dragging green firewood back to the fire ring and trying to burn it, and lots of trash. Littering is a constant problem.

Q: What other challenges do you face as a volunteer?

A: Some people look at us as interfering with their experience. You know—“All these rules and regulations! Why can’t I camp on the edge of a lake? Why can’t I camp anywhere I want? I should be able to build a fire anywhere I want.” But then you have other people who will go out of their way to help you. They're willing to stop, drop their pack, and pitch in to help you get a log off the trail. I would say for every miserable person you meet, you probably meet 15 to 20 good people—and I'm glad.

Q: What about wild animals? Any trouble with bears?

A: I see bears most years, and they can be a problem when people don't store their food correctly. But a couple of years ago, we had a problem with an aggressive moose on Stratton Mountain. It was chasing people and stranding them in the fire tower for hours, not letting them leave. This happened to be on the weekend of a big yoga festival that’s held every year at the Stratton ski area—so there’s all these young ladies in their yoga get-ups, and they're walking barefoot over to the tower to get the view. Well, the reason this moose was so obnoxious was because it was sick. We tried politely explaining to them that it doesn’t really do to be walking through moose diarrhea barefooted … but we couldn’t make them understand.

… and we're going to leave it there. Big thanks to volunteers like Jim, for taking on everything from fallen logs to ornery moose—and to you, for supporting The Trust for Public Land's efforts to keep the Appalachian Trail wild.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.