Your need for nature is more than a feeling

Your need for nature is more than a feeling

There’s something about time spent in nature that makes us feel better. Whether it’s a quick stroll around the block to think through a problem or a weekend in the wilderness to clear your head, you’ve probably experienced a boost just from getting outdoors. But why?

It’s a question that intrigued journalist Florence Williams. After two decades living near the mountains, a move to the city left her feeling down. Driven to understand the change in her own well-being, she began researching the connection between the outdoors and humans’ physical, mental, and emotional health.

Williams captures her findings in The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative. We caught up with her at her home in Washington, DC, to talk about the book—and why she believes park advocates need to talk about science.

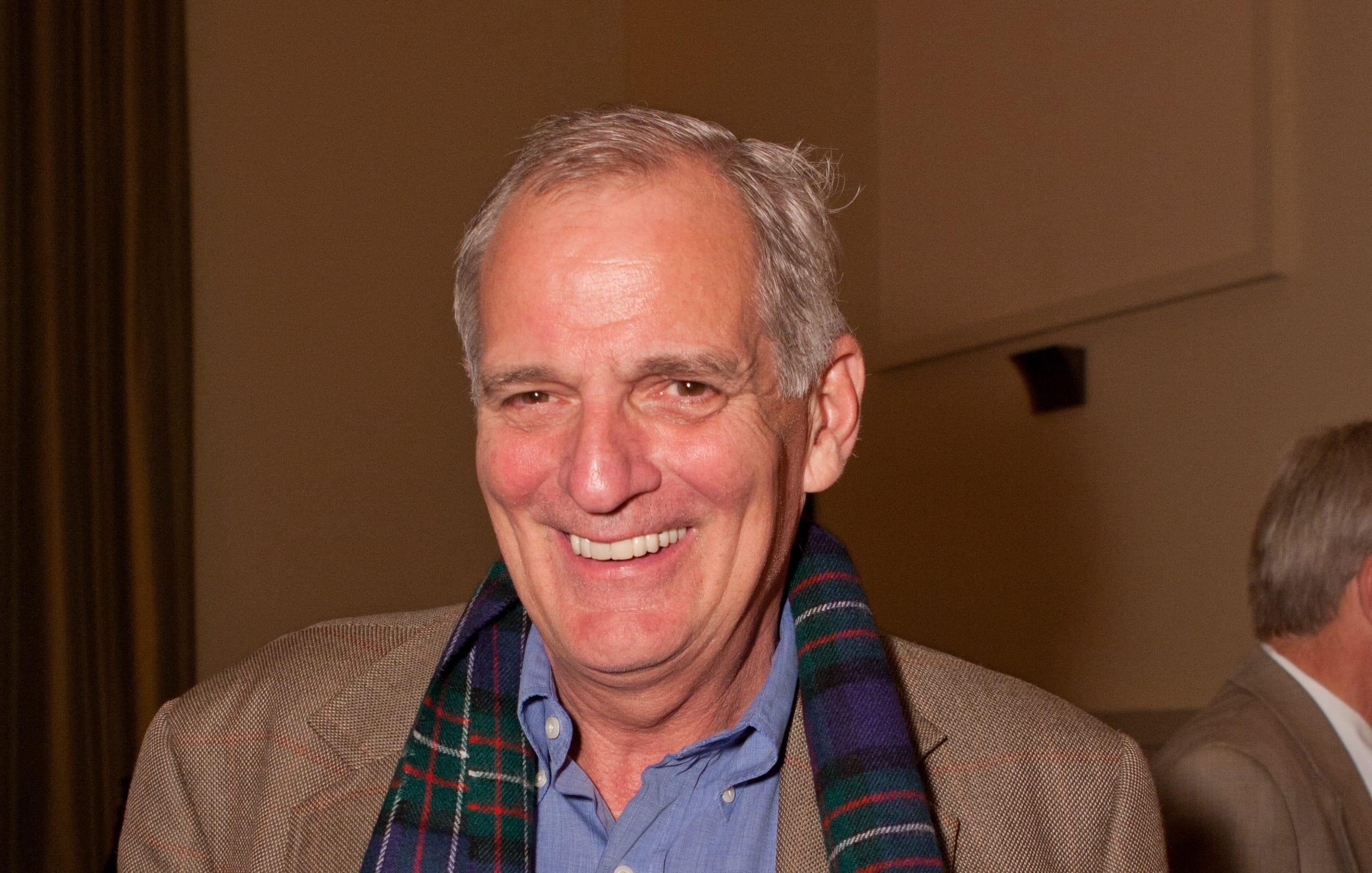

Florence Williams is the author of “The Nature Fix.”Photo credit: Sue Barr

Florence Williams is the author of “The Nature Fix.”Photo credit: Sue Barr

What happened when you moved to Washington, D.C.?

Living out in the Rockies, I got accustomed to feeling connected to nature—or at least aware of it—on a daily, almost hourly basis. Boulder is a big enough city, but nature is very integrated into life there: my house was right next to a trail, there was a creek nearby, and you’d even hear reports of mountain lions prowling city neighborhoods. Then we moved to D.C. for my husband’s job, and it was like a cortisol bomb went off in my head. I felt besieged by aircraft flying overhead at all hours, the constant traffic, the gray cityscape instead of sun and clouds on the mountains. I was short-tempered and on-edge.

That experience made me personally interested in the connections between nature and mental health. I started a multi-year journey researching the ways that nature affects us as individuals—and how, in turn, that can shape the societies we live in.

You traveled the world to investigate how other cultures integrate and interact with nature. What’s an example of an approach that’s different from how we do things in the United States?

I got a real lesson in sensory engagement in Japan. The Japanese don’t necessarily glorify wilderness in the same way that we do in America, in part because theirs is a very urban society. But they do tend to integrate nature into their daily lives, in everything from building design to just taking notice of what flowers are blooming and what birds are flying around.

Japan is also one of the places where people practice “forest bathing”, or shinrin-yoku. It looks like just a slow walk in the woods, but the idea is to fully engage all of your senses—to notice every part of your surroundings. Practitioners claim it’s a method of relaxation and restoration, and the research supports the idea that this kind of mindfulness does actually result in molecular changes in your nervous system. The Japanese government has poured millions into studying the practice.

Feeling like life stinks? Maybe you need a (forest) bath.

Feeling like life stinks? Maybe you need a (forest) bath.

Did anything you learn really surprise you?

I wasn’t surprised to learn that time in nature boosts our mood, but the idea that it can make us feel more socially connected and generous was new to me. I learned about a team of researchers in the early 2000s that analyzed crime rates at a Chicago public housing project. They found that buildings with the greenest courtyards had 56 percent fewer violent crimes reported than the buildings with the least greenery.

One theory is that as we experience awe or beauty, we also experience stronger social connections that make us want to look out for each other. That’s probably one of the reasons that many religions build such magnificent houses of worship: awe makes us feel like we’re part of something larger. The Chicago researchers concluded that the greener, more appealing courtyards drew people outside—which gave neighbors a place and a reason to get to know each other. They think that sense of community and investment helped prevent crime.

Why do you think it’s important to quantify and explain nature’s benefits in scientific terms?

Our society doesn’t fully appreciate or value the extraordinary things nature can do for us. If we want our institutions to take conservation and access to nature seriously, they need evidence. We spend a lot of our lives connected to these institutions—our children are in school for decades, governments design our cities, and hospitals provide us medical care. We need to take nature out of the realm of intuition if we really want this idea to permeate and help all people. Otherwise, the benefits of nature will remain available only to those of us who can afford it, and have been exposed to it from the beginning.

The hard work of greening cities is even more than the digging: it’s also about convincing policymakers that nature matters. Photo credit: Rob Badger

The hard work of greening cities is even more than the digging: it’s also about convincing policymakers that nature matters. Photo credit: Rob Badger

What do you hope your book will accomplish?

I’d love for planners and policymakers to take the evidence for the benefits of time outdoors more seriously—but I know making space for nature in our society is a complex challenge. So if I had one hope, it’s that I can just convince people to spend more time outside. Especially kids. If we don’t get exposed to the natural world as kids, we risk making a connection. E.O. Wilson coined the term “biophilia,” which is our innate desire to affiliate with nature— but even though it’s innate, it has to be cultivated, or you lose the affinity. I think we’re at grave risk of that with this generation. Today’s kids are spending half as much time outside as their parents did growing up. And we’re all susceptible to addictive technology that kind of sucks away those little windows of time we might otherwise use to be outside.

Are you taking your own advice? Has writing this book changed your habits or made it easier for you to live and thrive in the city?

Definitely. I pay closer attention to how I feel in different environments, and honor those feelings more. I learned while researching noise pollution that I’m particularly psychologically sensitive to sounds, so I’ve started to seek out the urban woodlands throughout D.C. And if I have a big deadline, I know—because I’ve exhaustively researched it from 20 different angles!—that going outside for a walk will help me look at that problem with fresh eyes, jumpstart my creativity, and improve my mood, pretty much every time.

What do you think? Does getting outside affect your health? How do you get your “nature fix”? Leave us a comment, or join us on Facebook!

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.