Few people understand the power of maps more than Breece Robertson.

As one of the nation’s leading experts using geospatial data to help communities protect the places that matter to them, Robertson has spent decades watching how people respond to maps. “Maps are magnets: unroll a map on the table during a meeting, and all eyes turn to it,” Robertson writes in her new book, Protecting the Places We Love: Conservation Strategies for Entrusted Lands and Parks (Esri Press), which published this week.

Photo: Esri Press

The book synthesizes many of the insights Robertson has gained through decades of leading mapping efforts, including her 18 years as the lead geospatial researcher at The Trust for Public Land. It’s full of memorable anecdotes, innovative approaches to using geospatial data to solve conservation challenges, and step-by-step guides for practitioners using Geographic Information Systems, or GIS, to accelerate the pace of land conservation worldwide.

We recently chatted with Robertson to learn about the book and what maps can do for parks and conservation.

Maps Inform and Unite

Whether it’s an ancient petroglyph marking reliable places to hunt or fish or your smartphone guiding you on the fastest route across town during rush hour, maps have long helped us organize and store crucial information about the world around us, Robertson says. When it comes to parks and conservation efforts, maps are just as critical. Robertson cites the example of the campaign to protect 58,000 acres in Wyoming’s Hoback Basin. The vast landscape near Yellowstone National Park has long been a favorite place for locals to fish, hunt, paddle, and hike. But in the 2000s, the Hoback was threatened by plans to drill for natural gas, a potential jolt for the area’s struggling rural economy.

Wyoming’s Hoback Basi. Robertson says it wasn’t until the community saw the scope of a proposal to exercise oil and gas drilling in the basin on a map that they were sparked to find a way to preserve the land instead. Photo: Dave Showalter

The turning point? The community seeing the impact of the proposed drilling on a map.

“When everybody saw where the roads would go, where the drilling pads would be, how it would fragment the habitat, and how it would impact their drinking water, the community sprang into action to say, ‘No—it’s not worth it to us to degrade all these important values in the name of economic growth,” Robertson says. In December 2012, The Trust for Public Land worked alongside residents to retire 58,000 acres of oil and gas leases, permanently protecting the Hoback from future drilling.

Maps Have a Point of View

No matter its accuracy or detail, a map reflects the worldview of its maker, Robertson says. The most useful maps are made by people who understand the power of those biases, and take steps to limit their influence. “Integrity around data and maps is really important,” Robertson says.

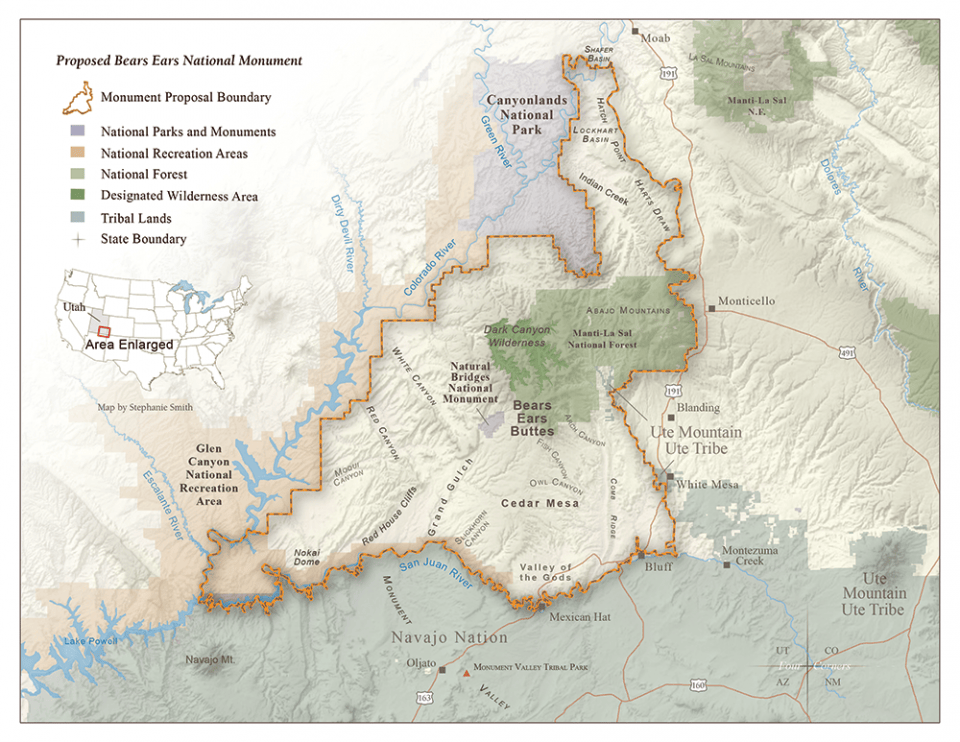

For instance, early maps published to rally support for the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah emphasized state lines and major highways. But for many of the members of the Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and Ute Indian Tribe who’ve long called this area home, “That map didn’t connect at all,” Robertson says. “The tribes brought a different relationship and view of the land that they didn’t see reflected on those early set of maps.”

So tribal leaders and members took a different cartographic approach. The resulting map emphasized landforms, rivers, and adjacent reservation lands and backgrounded political divisions like state boundaries.

“With that map, the whole conversation shifted. Right away it signaled to the Obama Administration that Bears Ears proponents were looking for a new kind of collaborative management that centered the tribes’ worldview and their relationship to the land,” Robertson says. “And in part through the process of co-creating a map, tribal leaders ended up forming what became the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition,” a group which continues to fight for the permanent protection of this imperiled landscape.

The map advocates submitted to President Obama for the proposal to create the Bears Ears National Monument. The north arrow doubles as a marking of where the Four Corners state meet, downplaying the significance of contemporary political boundaries. Photo: Stephanie Smith, Grand Canyon Trust

Maps Connect and Prioritize

Maps and data are animating forces in movements like 30 x 30, which aims to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and oceans by 2030. Scientists say reaching this goal is crucial to fight climate change and preserve critical biodiversity. But it will require a big increase in the pace and urgency of conservation efforts. Today about 15 percent of Earth’s land and 7 percent of its oceans are protected, which Robertson says we know because GIS technology has enabled everyone from private landowners to local land trusts to national organizations and governments to share their knowledge of protected lands. “And going forward, GIS technology and maps are important to determine, okay, which 30 percent is the most important for climate resilience and biodiversity? And to focus conservation efforts in the places they’ll make the biggest difference.”

At The Trust for Public Land, Robertson revolutionized the use of maps and data to measure, track, and prioritize park equity across the country. She led the team that developed the ParkScore® index, the definitive source for understanding how well America’s city park systems are meeting residents’ needs.

Each year our researchers compile in-depth data and analysis about park acreage, access, quality, and investment across the nation’s 100 largest U.S. cities. We collect and analyze this data and share it freely online because communities and elected leaders need accurate, up-to-date information to advocate for and prioritize the parks that are the foundations of healthy, equitable, resilient communities. And we can also use this data to see how this approach is driving change: In the ten years since Robertson launched the ParkScore index, we’ve tracked a nationwide 15 percent increase in the number of people living within a 10-minute walk of a park.

Author Breece Robertson Photo: Nicholas Lea Bruno

Want to learn more about the power of maps, or how conservationists are taking advantage of the latest in artificial intelligence and machine learning? Pick up a copy of Protecting the Places We Love.

Rising temperatures, bigger storms, and asphalt schoolyards pose significant risks during recess. Urge Congress to prioritize schoolyards that cool neighborhoods, manage stormwater, and provide opportunities for kids to connect with nature today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.