The Cost of Not Protecting Source Waters

- Increased Treatment Costs

- Protecting Forests Means Protecting Water Quality

- Increased Capital Investments in Treatment Technology

- Loss of Consumer Confidence—A High Price to Pay

Treatment and filtration, land conservation, new development and infrastructure—each of these has a price tag that impacts decisions about drinking water protection. For municipalities and water suppliers, budget constraints and the bottom-line factor in throughout the process. What’s important is to make informed assessments about the costs, both long- and short-term, of source protection in relation to other approaches.

Land use and protection decisions are often based on short-term (one to five years) revenue and expense projections for local governments, as elected officials decide how to balance land protection policies based on current budgets. However, the impacts of development on water quality and treatment costs are realized over the long term— five to ten years and longer, and are often ignored in land use planning processes. The short-term costs for protection of source lands can be high, and water suppliers, who understand the long term cost and public health impacts of watershed development, are not usually involved in land use or land protection decisions.

It is difficult to establish the impact of land use alone on water quality. By the time water quality degradation has become apparent and treatment methods need to be upgraded, it is often too late for municipalities and suppliers to choose source water protection as a means for addressing the problem.

Many communities that have experienced the increased treatment and capital costs of degraded water, and the quality of life impacts of fast growth, are now implementing regulatory and non-regulatory strategies to protect land and encourage more sustainable development patterns. These communities are learning that while land conservation is a big investment, it may also be a bargain compared to the long-term costs of treatment and contamination. This section summarizes the potential costs of not protecting a community’s source lands.

Mountain Island Lake Watershed, North Carolina

“When rapid development in Mecklenburg County began to impact the Mountain Island Lake Watershed, which provides drinking water to six hundred thousand county residents, it was a wake-up call to the community that we needed to act now to protect our drinking water,” says Ruth Samuelson, Mecklenburg County Commissioner. “In addition to the cost of treatment for a degraded water supply, the loss of our forests and natural landscapes threatened the quality of life in our community. Today, Mecklenburg County owns over 4,000 acres, 1/8th of the total, of Mountain Island Lake Watershed.”

The development of watershed and aquifer recharge lands results in increased contamination of drinking water. With increased contamination comes increased treatment costs. The costs can be prevented with a greater emphasis on source protection.

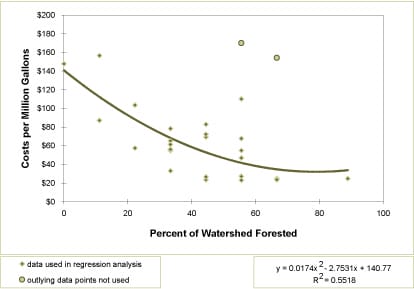

A study of 27 water suppliers conducted by the Trust for Public Land and the American Water Works Association in 2002 found that the more forest cover in a watershed the lower the treatment costs. According to the study:

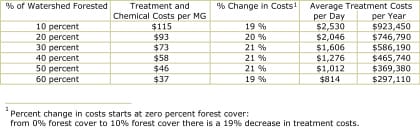

- For every 10 percent increase in forest cover in the source area, treatment and chemical costs decreased approximately 20 percent, up to about 60 percent forest cover.

- Approximately 50-55 percent of the variation in treatment costs can be explained by the percent of forest cover in the source area.

There was not enough data on suppliers with over 65 percent forest cover from which to draw conclusions; however, it is suspected that treatment costs level off when forest cover is between 70 and 100 percent. The 50 percent variation in treatment costs that cannot be explained by the percent forest cover in the watershed is likely explained by varying treatment practices, the size of the facility (larger facilities realize economies of scale), the location and intensity of development and row crops in the watershed, and agricultural, urban and forestry management practices.

The following table shows the change in treatment costs predicted by the analysis above, and the average daily and yearly cost of treatment if a supplier treated 22 million gallons per day—the average production of the surveyed suppliers.

A similar study was conducted in 1997 by the Department of Agricultural Economics at Texas A&M University. From a sample of 12 geographically representative suppliers, with three years of data, researchers found that:

- Suppliers in source areas with chemical contaminants paid $25 more per million gallons to treat their water than suppliers in source areas where no chemical contaminants were detected.

- For every four percent increase in raw water turbidity there is a one percent increase in treatment costs. Increased turbidity, which indicates the presence of sediment, algae and other microorganisms in the water, is a direct result of increased development, poor forestry practices, mining or intensive farming in the watershed.

Protecting Forests Means Protecting Water Quality

Some utilities understand that protecting forests means protecting water quality and are working to prevent future increases in treatment costs through targeted land conservation. Kirk Nixon at San Antonio Water System is developing ways to measure the water quality, quantity and financial benefits of their successful effort to protect approximately 15,888 acres of aquifer recharge land over the last five years, the total acreage from both the San Antonio Water System Sensitive Land Acquisition Program and the City of San Antonio Proposition 3 Initiative.

According to Nixon, “The benefits of these types of programs are quite difficult to quantify. It is a difficult task to compare actual land development and the associated storm water treatment required versus conserving land in a natural, undeveloped state. These are the very issues that we at the San Antonio Water System, in cooperation with other entities, are striving to resolve. Through a cooperative agreement with USGS, we are conducting pollutant loading studies, recharge and runoff estimation models, and hydrogeologic and vulnerability mapping projects. In the first phase of our study, we’re establishing gauging and sampling stations on small, specific land use watersheds, collecting the data and characterizing the impacts from various land uses on the Edward’s Aquifer Recharge Zone. In the second phase, we will calibrate a watershed model to predict runoff, constituent loads and recharge on the Bexar County portion of the recharge zone.”

Increased Capital Investments in Treatment Technology

The impact of development and loss of forest land on water quality happens over time and is usually greatest during heavy periods of rainfall. At first, heavy pollutant loads come as isolated events during storms. Gradually, larger and more complex pollutant loads appear with greater frequency and severity until an acute event or revised water quality regulations cause suppliers to alter treatment strategies or upgrade facilities.

Upgrading treatment systems can be extremely expensive. Between 1996 and 1998 the City of Wilmington, North Carolina spent $36 million to add ozonation and expand its treatment facility, in part as a result of an increase in industrial and agricultural runoff in their watershed. In 2000, Danville, Illinois invested $5 million in a nitrate removal facility to deal with spikes in nitrogen resulting from agricultural runoff. In 2001, Decatur, Illinois, invested $8.5 million in a new nitrate removal facility, also to deal with agricultural runoff.

New water quality regulations are often the final impetus for treatment upgrades. However, suppliers with protected source waters are less likely to be forced to invest in major upgrades because their pollution concentrations are more likely to remain below maximum allowed levels.

Acquiring Land Saves Money: Auburn, Maine

Auburn, Maine, saved $30 million in capital costs, and an additional $750,000 in annual operating costs, by spending $570,000 to acquire land in their watershed. By protecting 434 acres of land around Lake Auburn, the water systems are able to maintain water quality standards and avoid building a new filtration plant. Funding for the land acquisition came from a Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Loan to the Auburn Water Department.

Loss of Consumer Confidence—A High Price to Pay

When water quality causes illness or even just an unusual taste, odor or color, the public quickly loses confidence in the safety of its supply. An erosion of public trust costs both the supplier and the community, often leading to broader economic impacts, in addition to treatment and capital costs. Residents begin buying bottled water and household filtration systems, and local businesses that rely on clean water install their own filtration systems. In some cases, businesses and individuals may choose not to live or work in a community because of the perception of poor water quality.

The impacts of contamination and waterborne disease outbreaks should not just be measured economically. They should also be measured in human terms. In an inquiry into an E. coli outbreak in Walkerton, Ontario, in 2000, the investigator wrote that the most important consequences of the outbreak were in the “suffering endured by those who were infected; the anxiety of their families, friends, and neighbors; the losses experienced by those whose loved ones died; and the uncertainty and worry about why this happened and what the future would bring.”

Iron and Manganese in Maynard, Maine

The town of Maynard, MA, a rapidly developing community in the Boston Metropolitan area, experienced a dramatic increase in the levels of iron and manganese in their ground water as a result of increased urban runoff. The water had become discolored, leading to a surge in complaints from customers concerned about the safety of the water. Although discoloration from iron and manganese is not a threat to public health, removing it requires expensive treatment. As a result of public concern, the town voted to approve a new $4.6 million treatment facility.