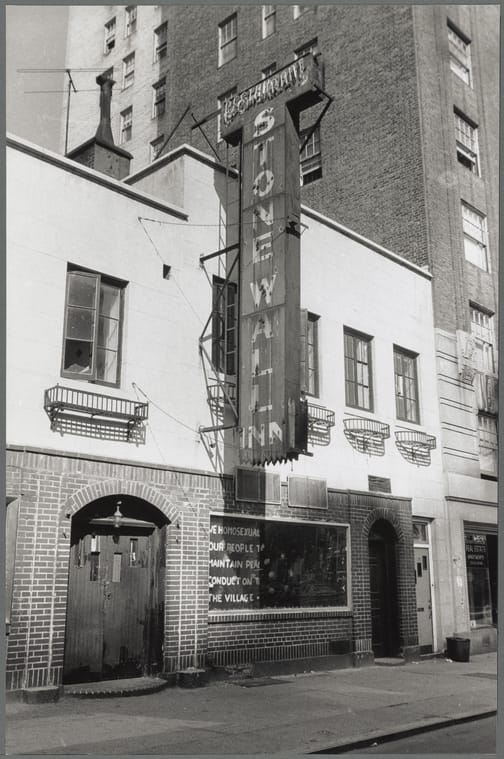

In the late 1960s, the Stonewall Inn—a bar on the ground floor of a modest brick building in Greenwich Village—was a popular gathering place for New York City’s LGBTQ+ community. Police raids on gay bars in the city were common at the time, so nobody was surprised when officers barreled into the Stonewall Inn late on June 28, 1969. But that night, rather than submitting to arrest or dispersing, some of the patrons fought back.

It was a spontaneous act of defiance that exploded into five nights of violent clashes between police and the LGBTQ+ community and its allies—events widely recognized as the spark that ignited the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement.

The Stonewall Inn in 1969, the year of the riots. Photo: Diana Davies/New York Public Library

“I think Stonewall came out of the protest spirit of the 1960s, when so many people started to stand up and try to take what was theirs,” recalls longtime Greenwich Village resident Gil Horowitz. “Gay people were definitely not immune to a desire for equality—we just got started a little later.”

Horowitz and his boyfriend at the time joined the second night of demonstrations at Christopher Park, a tiny patch of green across the street from the Stonewall Inn. Horowitz was arrested and hauled to the police station, where he recalls officers beating protesters with nightsticks. “The violence against gay people that I witnessed during the demonstrations and at the precinct horrified me beyond anything I’d seen in my life,” he says.

The riots drew national media attention and electrified the LGBTQ+ community. People who had been resigned to concealing their sexuality began to envision a different future. “After the riots, gay people in the village no longer had that beaten-down look,” Horowitz remembers. “We started to feel we could show affection for each other in public. What had previously been hidden in the shadows of the Stonewall Inn was now out in the open.”

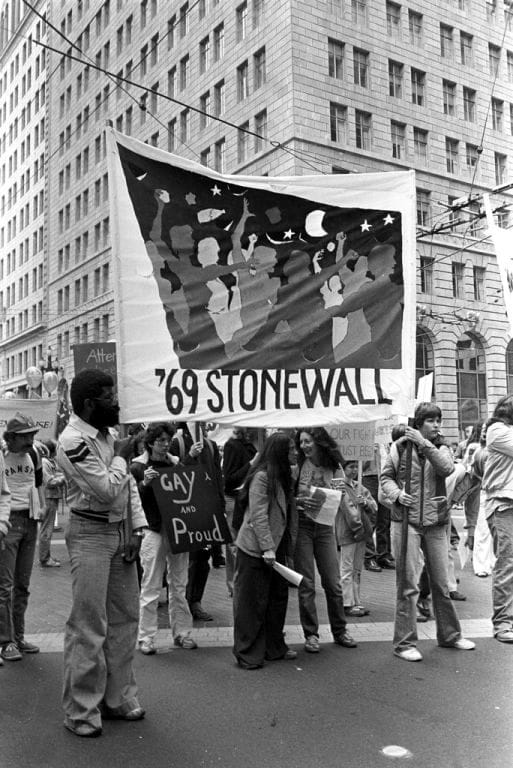

On June 28, 1970, a year after the Stonewall uprising, activists held the world’s first gay pride marches in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Chicago. The event has since expanded internationally. But don’t call it a parade, Horowitz insists. “It is a march. You march in protest. You have a parade when you’ve won,” he says. “We are far from winning, but we’re getting there.”

A year after the Stonewall riots, activists held the first gay pride marches in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco (above). Photo: Marie Ueda/Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society

The Stonewall Inn, meanwhile, closed down shortly after the riots. It returned in the 1990s only to close again in 2006. “I couldn’t fathom that this place would sit empty,” says Stacy Lentz, who, with two business partners, reopened the bar in 2007. “To me, this is birthplace of gay rights—what happened here in 1969 sparked a revolution across the country and even around the world. I wanted to be a part of keeping that history alive.”

These days the Stonewall Inn welcomes a diverse crowd from across the LGBTQ+ community and beyond. Across the street, Christopher Park is a frequent gathering place for protests, celebrations, and vigils. “People gravitate to this spot to show solidarity and share their stories,” says Lentz. “It gives you goosebumps to know you’re standing on the shoulders of the people who rioted here.”

When the Supreme Court ruled in support of marriage equality in June 2015, thousands of people packed the streets around the park to celebrate. And in the days following an attack on an Orlando nightclub, the mayor of New York City and the governor of New York were among the thousands who gathered here to mourn the dead and protest the violence.

After a shooting at gay nightclub in Orlando, the Stonewall Inn was the site of a vigil that drew thousands of mourners. Photo: Elisa G Schneider/Flickr

In June 2016, President Obama designed Stonewall National Monument, the first national monument dedicated to telling the story of the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. “I believe our national parks should reflect the full story of our country—the richness and diversity and uniquely American spirit that has always defined us: that we are stronger together. That out of many, we are one,” the president said in a YouTube video announcing the monument. Trust for Public Land helped New York City prepare for the transfer of the property, paving the way for its permanent protection.

For Lentz, who was born just a few months before the first gay pride march in 1970, a national monument is a fitting tribute to a movement that she has grown up alongside. “This solidifies so many people’s actions, work, and dreams of equality. We have fought so hard to change hearts and minds. We’ve been persecuted for years, and to have your government recognize what people have gone through and fought for—it’s an incredible thing for our community.”

“This national monument acknowledges that we’re a part of the fabric of America,” agrees Horowitz. For him, the monument’s significance extends outside Greenwich Village and beyond the LGBTQ+ community.

“The national parks are supposed to tell the stories that are important to the whole country,” he says. “Ours was a big story yet untold.”

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.