As COVID cases rise, make parks a public health priority

As COVID cases rise, make parks a public health priority

Coronavirus cases are rise again across much of the nation. As Americans look for ways to stay healthy and connected throughout the winter to come, we caught up with Trust for Public Land Community Health Director Sadiya Muqueeth to talk about the critical importance of parks during the pandemic.

Trust for Public Land Community Health Director Sadiya MuqueethPhoto credit: Shae McCoy

Trust for Public Land Community Health Director Sadiya MuqueethPhoto credit: Shae McCoy

How does infrastructure like parks affect community health?

Take any negative health outcome, like diabetes. Your risk of diabetes is correlated with whether you eat a nutritious diet and get enough exercise. So the traditional, clinical approach to diabetes prevention has been to address these individual behaviors, to educate patients in the doctor’s office about the importance of their own actions.

But so much of behavior is not actually a matter of individual choice. Are there grocery stores within walking distance of your house, and do they sell affordable, healthy food? Do you live in a neighborhood where it’s safe to go out for a jog? Do you have a park or a trail to visit or are you exercising along a busy street?

Why are some neighborhoods healthier than others?

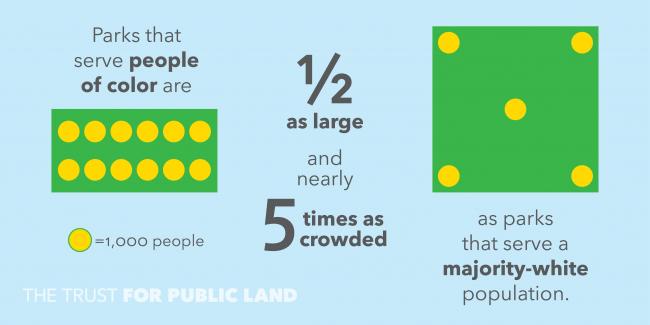

It’s the effect of generations of inequitable investment. Across the country, low-income communities and communities of color have less access to healthy food, stable housing, and transportation. Over 100 million people in America don’t have a park within a 10-minute walk of home. We published new data analysis this summer showing that, across the country, parks in communities of color are, on average, about half as big as parks in white neighborhoods and serve five times as many people. And parks serving majority low-income households are, on average, a quarter the size of parks in high-income neighborhoods.

Photo credit: The Trust for Public Land

Photo credit: The Trust for Public Land

What does that mean for communities facing the coronavirus?

The coronavirus crystallized the urgency of addressing these structural inequities. So many of the places where we care for ourselves and our communities have been limited or closed—your gym, your place of worship, your coffee shop. What that means is, if you live within walking distance of a park, if your neighborhood’s streets are cool and shaded, you could safely get outside wearing a mask and get the exercise you need, and you had a place where you could maintain those social connections that are so important for mental health.

What if you don’t have a park close to home?

You are vying for the same outdoor space as many of your neighbors. And since our data show parks are not equally distributed, we know that’s likelier to be the situation in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. These are the same communities who’ve been most affected by COVID-19—in part because of historical and current resource deprivation, people of color experience higher rates of health conditions that are risk factors for getting seriously sick from a coronavirus infection.

Why spend money on a park to improve health, instead of basic necessities like housing or food?

I actually think that’s a false choice. People need access to health care and education. People need affordable food and well-paying jobs. And people need access to nature. For far too long, disenfranchised communities have had to choose which benefit they’re “allowed” to have. But as a society, we can afford all of these things. It’s a matter of focusing our support among communities who are already working to fix the social and structural conditions that cause health problems in the first place.

The United States spent $3.5 trillion on health care in 2017—but spending on public health made up only 2.5 percent of that. That’s a sign that our approach to health is still so concentrated “downstream,” on reacting to the consequences of structural inequities in a clinical setting—instead of investing “upstream” on interventions like equitable parks, which give all people the opportunity to live healthier lives.

“So many of the places where we care for ourselves and our communities have been limited or closed,” Muqueeth says. So people with parks close to home have an easier time getting outside, getting exercise, and maintaining important social connections.Photo credit: Allana Wesley White

“So many of the places where we care for ourselves and our communities have been limited or closed,” Muqueeth says. So people with parks close to home have an easier time getting outside, getting exercise, and maintaining important social connections.Photo credit: Allana Wesley White

How do you approach those structural conditions?

You cannot make a difference at a structural level if you’re acting all alone. So we partner with neighborhood residents and health experts to make sure that the parks we design reflect both the needs and desires of the community, and are grounded in principles of good health. The Colorado Health Foundation has funded park development projects in Denver and Colorado Springs, because those investments have been shown to benefit public health. They also fund our community engagement efforts, helping to create health-focused design and inclusive programing at parks throughout the region. Because it’s not just whether or not you have a park nearby: it’s the safety, quality, and inclusiveness of these spaces that promote health.

We also advocate for policies that will send resources upstream. This summer, Congress passed a bill that fully funds the Land and Water Conservation Fund, a crucial source of public funding for parks and open space across the country. Now, communities have more stable and dependable funding they can use to fix these longstanding environmental inequities.

How do we know what investments will make the biggest difference?

Five years ago, there was no nationwide database for analyzing the relationships between environmental inequities like too little open space or too few trees, and health risks like high heat, sedentary activity, and air pollution. So our research department built that database, and we use it to guide our work and to equip others—from community members to elected leaders—to advocate for the parks they need.

Download our special report, “Parks and the Pandemic,” to learn more about our research on parks, health, and equity.

A version of this interview appeared in the Fall/Winter 2020 issue of Land&People magazine, a benefit to members of The Trust for Public Land. When you make a gift before December 1, Giving Tuesday, one of our generous supporters will TRIPLE any amount you give, up to $250,000. Please take a moment and triple your impact to protect and care for our nation’s public lands now, when they need our help—and we need them—the most.

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.