Dr. Scott on ‘How to Raise a Wild Child’

Dr. Scott on ‘How to Raise a Wild Child’

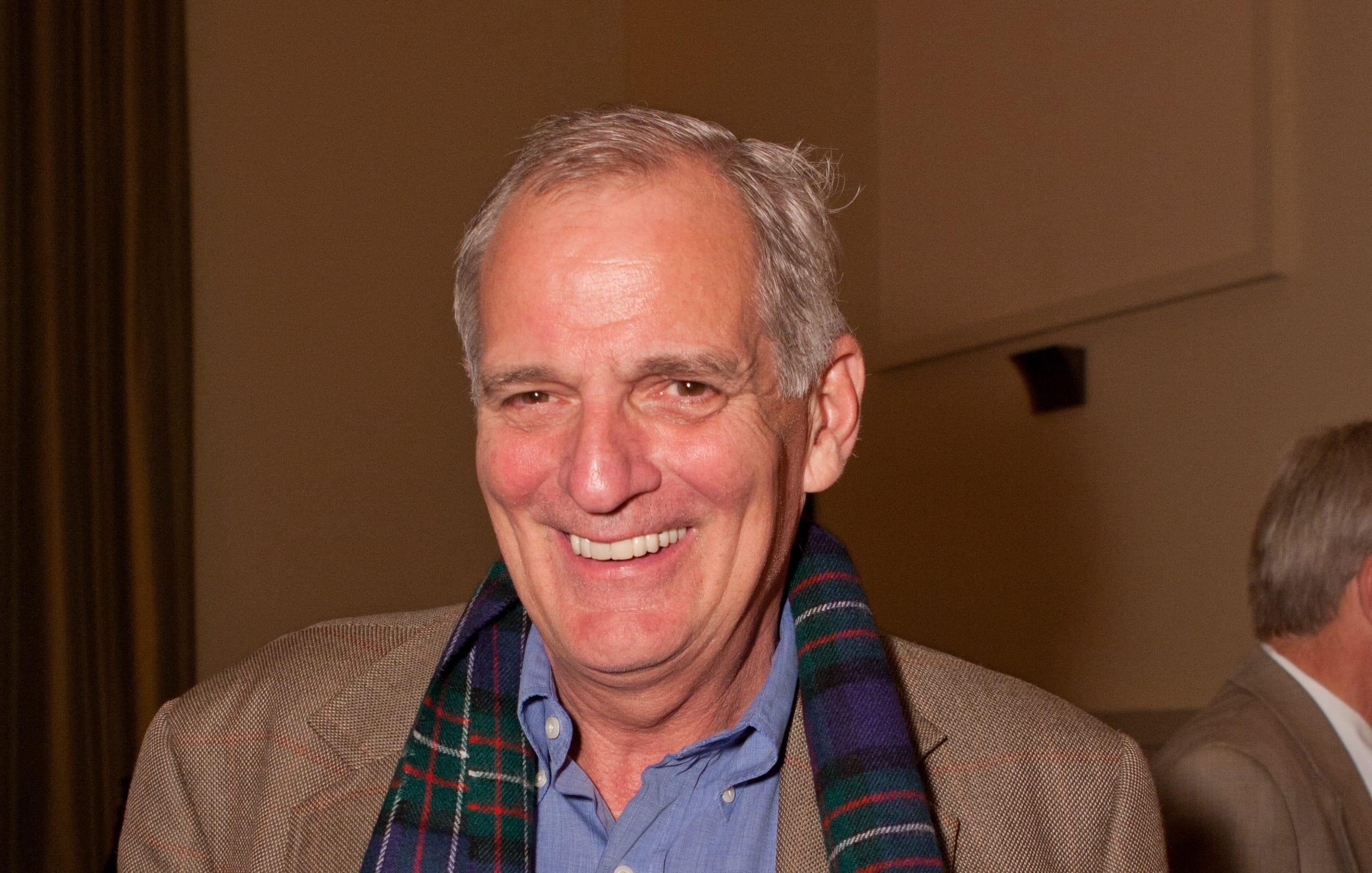

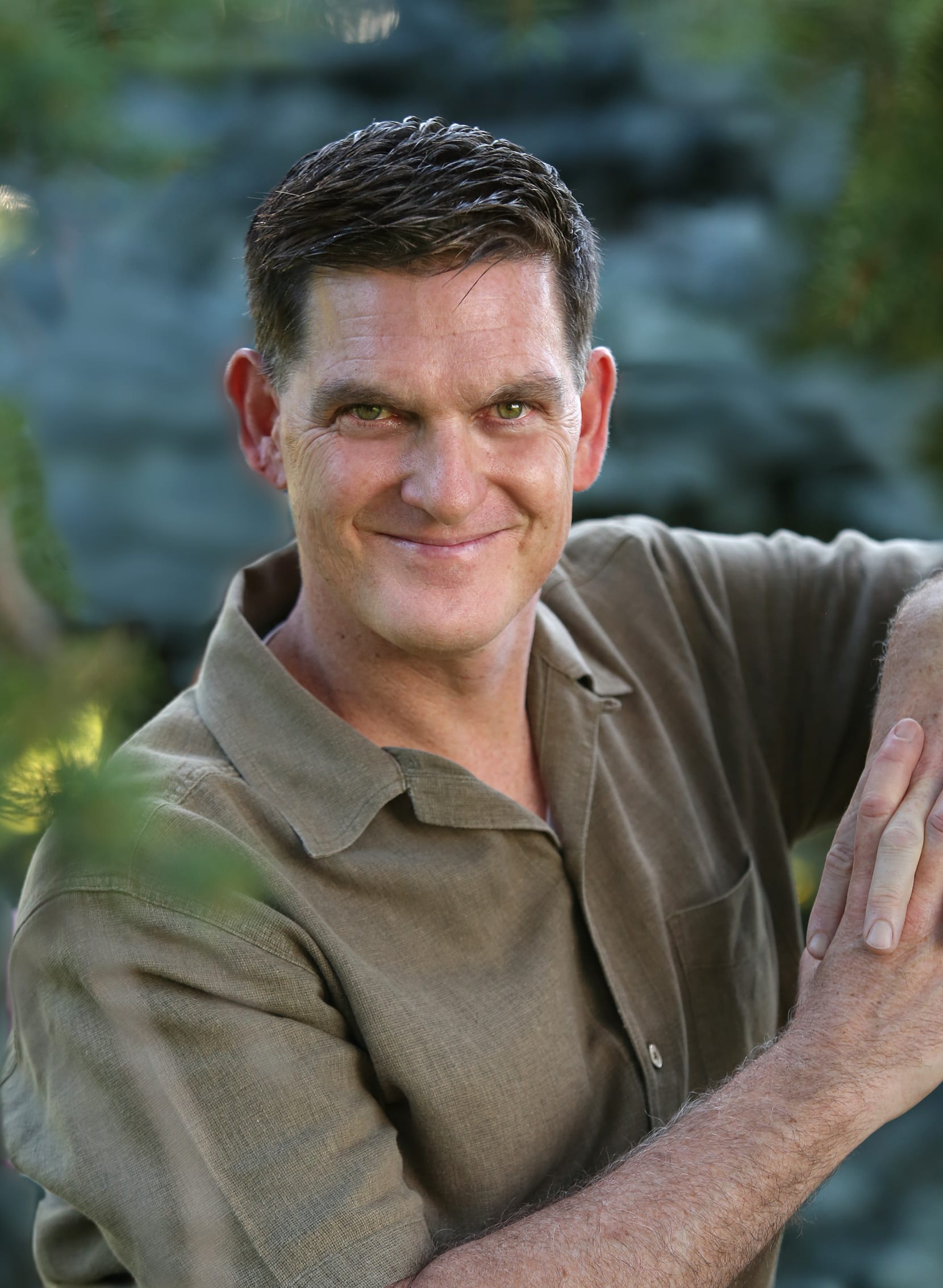

The most pressing environmental challenge of our time may not be species extinction, habitat destruction, or even climate change. If you ask Scott Sampson—better known as “Dr. Scott”—it could actually be our disconnection from the natural world around us.

A paleontologist and chief curator at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, Dr. Scott has built his life’s work around inspiring the next generation of environmentalists. As the host of PBS children’s series Dinosaur Train, he inspires the curiosity and wonder of of young fans, concluding every episode by encouraging his viewers to “Get outside, get into nature, and make your own discoveries!

“You can’t solve those other crises unless people care about where they live,” says Sampson. “And why would they care if they don’t spend time outside, and never develop an emotional connection to nature?”

His new book How to Raise a Wild Child: The Art and Science of Falling in Love with Nature provides tips and tools for bringing up kids who are excited to play outside. We tore through our copy—and then called Scott with some questions.

At The Trust for Public Land, we’re all about connecting people to nature. Why is that especially important for children?

If we don’t give kids the opportunity to connect with nature, we rob them of an essential part of childhood. Research shows that free play is critical for brain growth, body growth, and emotional growth, and that outdoor play is far more creative, innovative, and social than play conducted inside. The outdoors provides this multi-sensory smorgasbord of opportunities to engage, not just on a computer screen, but through sight, sound, touch, and smell.

So, kids need nature. But how can parents encourage them to get outside?

Kids need two basic things to grow up with a strong connection to the natural world: abundant time outdoors and a “nature mentor”—at least one adult who themselves feels that connection. You don’t need to be an expert and you don’t need to have all the answers. In fact, you don’t need to have any answers—the key is to get kids outside and spark their sense of wonder by asking them questions about what they encounter. It’s that simple.

What about families who live in cities? How can they experience the natural world?

Too often, people think of nature in terms of national parks, or mountains, forests, or beaches—someplace far away. But most of us can’t make it to those places very often. We know from a variety of studies that deep nature connection happens through everyday occurrences, and the best place to connect with nature is right where you live.

In the book, I offer simple ideas for nature mentors to foster that connection. For young children, it’s mostly about unstructured play. For older kids, “sit-spotting” can be powerful: Find a spot to sit and observe the nature around you—a backyard, neighborhood park, or even a schoolyard. The key is to return often to the same place and open up all your senses. Just like our connections with people, you can’t develop a deep relationship with nature without abundant direct experience.

Kids learn about the natural world in the classroom. How is an activity like “sit-spotting” different?

I would argue that building awareness of the plants and animals around you is more important than facts and scientific understanding. It’s not about having kids learn the scientific names of local life forms, though that’s fine if they’re enthusiastic. Instead, the key is growing an awareness of—and emotional attachment to, nearby nature—how it works and how it changes with the seasons and time of day. In this sense, the information that matters most is the kind that builds a sense of wonder.

Why should schools prioritize incorporating natural elements into their landscaping and recess spaces?

“Outdoor classrooms” with native plants, vegetable gardens, and other natural elements help kids get healthier. Students are less stressed and more social. There is less bullying and more creativity. And you’ve got this amazing learning environment, because it literally is alive and changing all the time.

Imagine empowering kids by asking them what kinds of plants and animals they want living in their schoolyards, and then helping them achieve that goal by planting native plants. This activity can be part of the science curriculum, the English curriculum, and even the social studies and history curriculum. The kids can use the schoolyard as a microcosm for understanding where they live, how that place came to be, and how it might change in the future. Now imagine if we empowered kids to re-green schoolyards all over our communities. They would have a powerful role in literally transforming cities, generating habitats for all kinds of native animals and plants.

That sounds a lot like our work on playgrounds on schoolyards.

I’m thrilled by The Trust for Public Land’s Parks for People initiative and your efforts to put a park within a ten-minute walk of every American. You’re promoting nature connection in cities, arguably more so than any other conservation organization. Given that the great majority of us now live in urban areas, cities must become the front line of the children-and-nature movement, and The Trust for Public Land is leading the way.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to allocate funding to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities by championing the Outdoors for All Act today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.