Man on the run

Man on the run

Update: We joined #GobiMarch contender Kyle McCoy in a Twitter chat July 7. Check it out!

155 miles. 7 days. 117-degree heat. They call it the Gobi March, an annual ultramarathon that draws some of the world’s most elite athletes to a remote desert in western China. It’s just the kind of challenge that Kyle McCoy lives for.

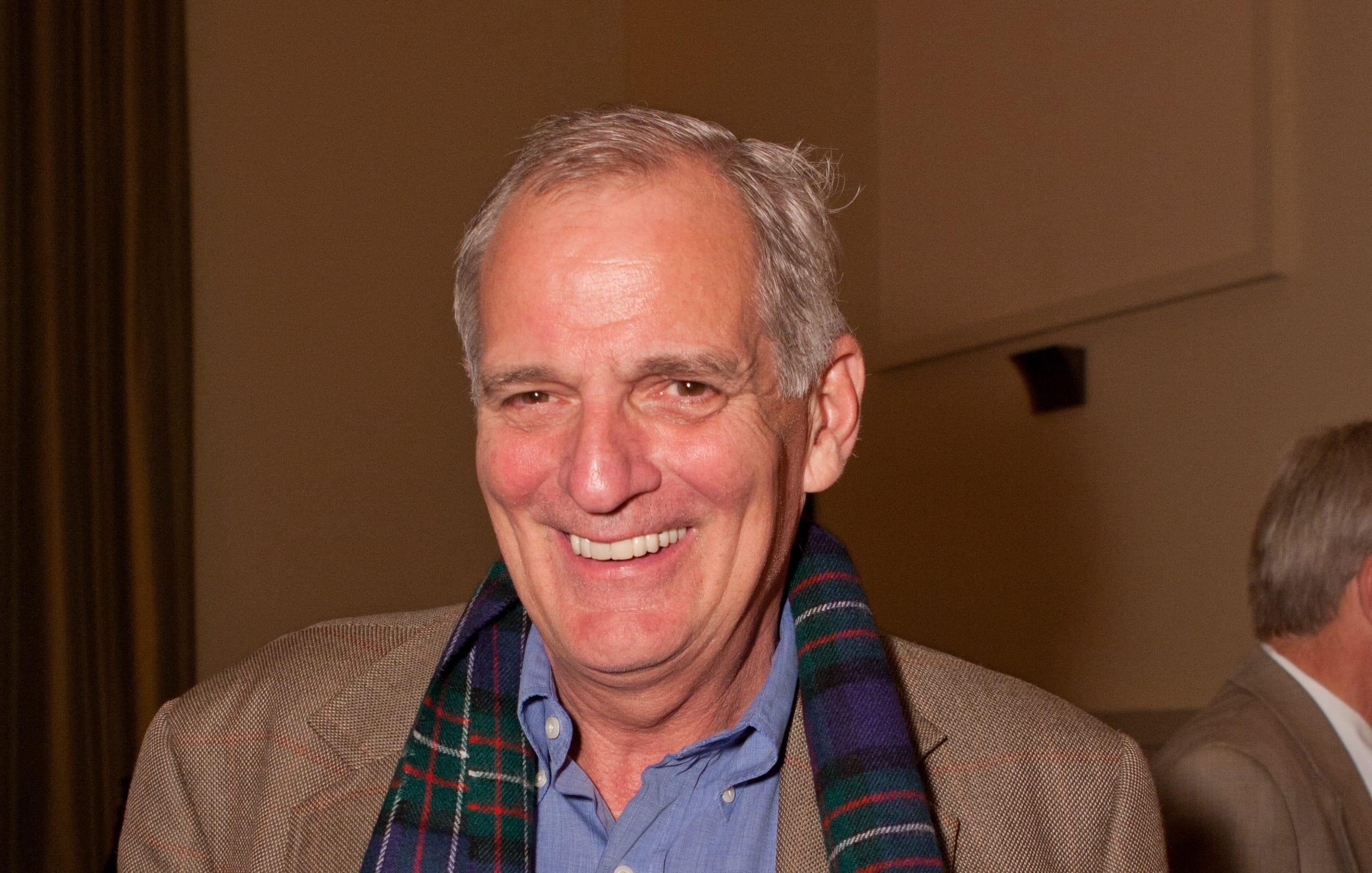

A former captain in the U.S. Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment and 82nd Airborne Division, McCoy served in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. Now a banker based in Washington state, McCoy ran the Gobi March to support The Trust for Public Land—raising $50,000 in donations in the process. He took a break from icing his knees to chat about his record-breaking accomplishment.

Why do you race? What draws you to extreme endurance events?

I love seeing how far I can push myself—the human body can go farther than any of us expect. I also find that when I run, I feel better all around. I sleep better, and I’m happier.

How has your time in the army influenced your interest in endurance racing?

No question, being an Army Ranger has had a big impact. You go through a lot to become a Ranger, and I got pretty good at suffering. In these races, you’re wearing a backpack and tackling extreme terrain, carrying all of your gear and taking care of your body through some pretty tough conditions. I find that I’m more competitive in those types of environments. I’ve kind of gotten used to it over time, and now I love that part of it. I also enjoy the camaraderie that comes along with commiserating with other racers and suffering together to achieve a goal.

Tell us more about the Gobi March.

The Gobi is known as the windiest non-polar desert on Earth. It also has the most variety in terrain and temperature. The Gobi March is one of four races in the 4 Deserts race series, which also includes the Atacama in Chile, the Sahara in Africa, and Antarctica, which is technically a desert.

You’ve run the Atacama and the Sahara, too. How is Gobi different?

The Gobi was the most grueling desert race I’ve competed in so far because of 85-degree temperature swings—from 30 degrees to about 115 degrees. That’s a huge swing, and I wasn’t prepared for it. The Yukon-Arctic Ultra was the coldest race I’ve ever done—it got down to negative 30 degrees. But I was prepared for that. I had all the right gear. In the Gobi, I didn’t anticipate that it would sleet and snow on me within the first two days and then soar to well over 100 degrees.

What were the high points and low points of this race?

The high point was winning a stage—that was a first for me. There were 161 competitors from 40 countries, and to cross the line in front of them all was an amazing feeling. The low point was on mile 44 of the 50-mile day when I started throwing up. I got pretty dehydrated and I was showing signs of heatstroke. When you start throwing up, it’s an indicator that things are going downhill quickly. I had to stop and rest at the checkpoint until I could finish the final six miles.

We heard that officials were forced to cancel the last leg of the race. What happened?

It was a bit of an anticlimactic finish, but it sure was wild. An incredibly huge sandstorm rolled through camp after the 50-mile leg, when everyone was exhausted. I couldn’t believe how long it went on—it felt like forever. And when the storm was followed by torrential rain, officials called the race. It was disappointing to go through all of that and not be able to cross the finish line, but at least there were only seven miles left to run.

But you still finished third overall. In fact, the top three spots all went to Americans, right?

Yes. That was another high point. This is the first time that any one country has not only placed top three in an overall race, but also on any individual stage.

You live in Seattle, in part for the great parks and open space. What are some of your favorite spots to run?

The short answer is everywhere. Training for a race like this, you have to put in a lot of miles. My favorite route starts by going through Myrtle Edwards Park and the Olympic Sculpture Park—which was created by The Trust for Public Land.

You raised $50,000 for The Trust for Public Land during this race. What about our mission most resonates for you?

The Trust for Public Land is creating parks and land for people to enjoy. It’s not just conserving land: we want people to engage with the land. As a trail runner, I love that aspect. I’m a big believer in parks and the value that they create for cities and for people in general.

What do you think the parks of tomorrow will look like?

In the future—and we’re already seeing this in places like Seattle and New York and Chicago—the parks of tomorrow aren’t contained to one fixed area, but are entire trail systems.

Why do people need parks?

It’s a health issue, and by that I mean the health of people and cities. People use parks to get exercise and connect with nature, but parks are also an indicator of the health of a city’s economy. I think that’s why I like The Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore system. It keeps cities accountable to how well their park systems are doing and encourages investment.

Rising temperatures, bigger storms, and asphalt schoolyards pose significant risks during recess. Urge Congress to prioritize schoolyards that cool neighborhoods, manage stormwater, and provide opportunities for kids to connect with nature today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.